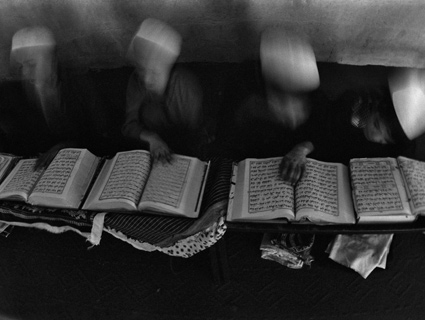

Louie Palu/ZUMA

Immediately after last month’s terror attacks in Norway, Islamic extremism shot to the top of almost every list of suspected culprits. Among the soothsayers of creeping Shariah, there was never any doubt who was responsible. Others’ more rational, if hasty, assessments of Norway’s threat matrix pointed to the same (wrong) conclusion. For all their differences, both lines of reasoning shared a common assumption: that the sheer volume of Muslim terrorists out there made their involvement likely. Or as Stephen Colbert skewered the media’s rush to judgment: “If you’re pulling a news report completely out of your ass, it is safer to go with Muslim. That’s not prejudice. That’s probability.”

Charles Kurzman begs to differ. In his new book, The Missing Martyrs, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill sociology professor rejects that Muslims are especially prone to violent extremism. “If there are more than a billion Muslims in the world, many of whom supposedly hate the West and desire martyrdom,” he asks, “why don’t we see terrorist attacks everywhere, every day?”

In theory, we should. After all, there’s any number of ways a terrorist committed to murdering civilians could attack (and our gun lobby certainly isn’t making weapons harder to get a hold of). But we don’t. No Islamist terrorist attack besides 9/11 has killed more than 400 people; only a dozen have killed more than 200.

As it turns out, there just aren’t that many Muslims determined to kill us. Backed by a veritable army of fact, figures, and anecdotes, Kurzman makes a compelling case. He calculates, for example, that global Islamist terrorists have succeeded in recruiting fewer than 1 in 15,000 Muslims over the past 25 years, and fewer than 1 in 100,000 since 2001. And according to a top counterterrorism official, Al Qaeda originally planned to hit a West Coast target, too, on 9/11 but lacked the manpower to do so.

Even so, it sure seems there are a lot of Muslims committed to the West’s destruction. What else to make of the celebrations in Middle Eastern streets after 9/11? Or Pew Research Center opinion polls of multiple predominantly Muslim nations showing significant support for suicide bombings? But Kurzman warns against conflating anti-Americanism with actual willingness to engage in terrorism. In reality, he says, the young man sporting the bin Laden T-shirt in Islamabad is probably more like the American teenager in Berkeley with the Che poster on his dorm room wall than a future Al Qaeda jihadist.

Yet even if only 1 in 100,000 Muslims is a terrorist, that still leaves something like 15,000 terrorists from a global population of around 1.5 billion Muslims. Surely that’s enough to inflict serious damage? It could be—and Kurzman concedes that Islamist terrorism should be taken seriously—but in practice, several factors conspire against Al Qaeda and its allies’ aspirations of regularly striking Western targets with spectacular attacks.

For one thing, Islamist terrorists are bitterly divided between globalist groups like Al Qaeda and localists like the Taliban and Hamas. The Taliban, for instance, opposed (and still opposes) Al Qaeda’s international ambitions, so much so, Kurzman claims, that its foreign minister sent an envoy to warn American and UN officials in the summer of 2001 about a possible, albeit unspecified, attack. Meanwhile, rifts within the Muslim world about issues like democracy, liberalism, and the role of women have crippled support for global jihadists. Insistent that all streams of Islamic thought conform to their rigid doctrines (and willing to murder fellow Muslims to make the point), Al Qaeda and its affiliates have alienated millions of potential supporters, rendering themselves far easier targets for unsympathetic Middle Eastern regimes to go after.

After pressing his case with almost prosecutorial precision for the first two-thirds of the book, Kurzman’s analysis veers off the rails as he detours into an alternately banal and pedantic discussion of everything from America’s need to balance liberty with security to the lexicological origins of sociology. In a case of epically bad timing, he devotes the better part of six pages to praising recently discredited philanthropist Greg Mortenson as “a role [model] for American foreign policy.” Kurzman is unfortunate more than anything else here, but after arguing that American foreign policy doesn’t really affect Muslims’ views of the US, his sudden fawning over Mortenson’s in-vogue “hearts and minds” counterterrrorism strategy is somewhat befuddling.

Still, Kurzman’s hard-headed empirical approach to an issue so often locked in emotion-fueled back and forth makes The Missing Martyrs (or at least most of it) a must-read. Early on, he states his aim: “to reduce the panic by examining evidence about Islamist terrorism—the actual scale of it and the reasons it is not more widespread.” It’s an important goal—perhaps more so now than at any point in recent memory—and Kurzman has made a valuable contribution.