On a summer day in 2015, Renata and more than a dozen women, all strangers from different parts of the country, sat in a semicircle on the living-room floor of a house, deep in the rural South. A lean twentysomething with a wide smile and olive skin, Renata was the only nonwhite person in the group. And she felt conspicuous in other ways too—many of the women struck her as kind of “new agey,” and some had been involved in a “crystal energetics” midwifery program. All of them had big red binders full of worksheets and documents related to the topic at hand: how to help women self-induce an abortion. “My initial thought,” she recalls, “is, ‘What the fuck did I get myself into?'”

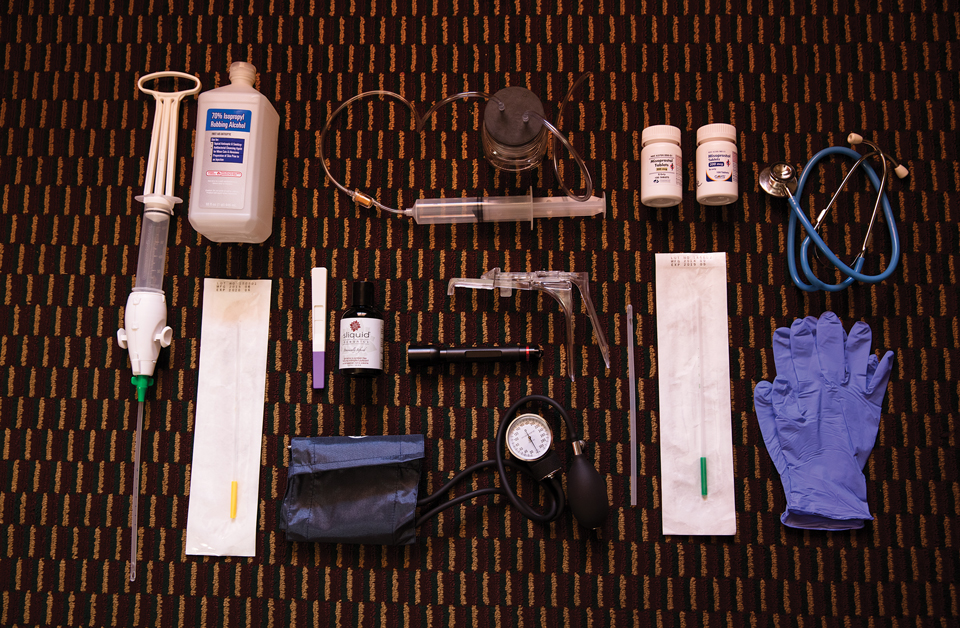

Renata had come from Arizona to attend the weeklong training. She learned how, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white male doctors consolidated their professional power in part by sidelining female and often nonwhite midwives and other community healers. She learned which drugs and herbs induce a miscarriage and where to buy the small, plastic, strawlike instrument that is inserted into the uterus and suctions out an unwanted pregnancy. If problems arise, what should one say to avoid scrutiny at the emergency room? In which states is self-induced abortion, and helping women self-induce, a crime?

On the second day, the group split into pairs, and in different rooms they practiced pelvic exams. Renata (whose name, along with those of other providers and clients in this story, has been changed) and her partner, propped up by pillows, tried not to pinch each other with the plastic speculum they were still learning to use. “It was emotional,” she remembers. “It’s a heavy topic, and you’re working with each other’s bodies.” The next day, a member of the group demonstrated on a woman having her period how a manual vacuum aspiration device, a handheld plastic syringe used by clinics for first-trimester abortions, could pull out the menses—or a pregnancy.

As long as women have had unwanted pregnancies, other women have helped them resolve the problem. After the mid-19th century, when abortion was outlawed, women either found a physician who did it on the sly or turned to traditional helpers, a practice that continued even after the Supreme Court legalized abortion in 1973. Today, as abortion rights are restricted at an unprecedented rate—between 2011 and 2016, more than 160 clinics closed—this informal network of nonmedical providers is responsible for a small but significant number of abortions nationwide.

Renata is part of a growing underground movement of people across America who have taught themselves to help women terminate pregnancies without a doctor. I talked to dozens of these clandestine providers, and our conversations offer a rare glimpse into a world that is shrouded in secrecy and fear. Some urged me not to write about their work. But their efforts reveal a new aspect of how the war on reproductive rights has played out, and how a new generation of activists has come to believe that it’s reasonable to handle this aspect of women’s health care outside a medical setting. And they are determined to give more women that opportunity, no matter the legal risk.

In the nearly three years since her training, Renata has helped about 20 women have abortions in Arizona, a state extremely hostile to abortion rights. She says she knows as many as 75 people, some of whom are queer or gender-nonconforming, who either provide these services or train others. For a 2016 study, University of Washington researcher Alison Ojanen-Goldsmith asked 19 people doing home abortions to count everyone they knew who had used alternative abortion methods. All told, the group identified 843 people, some of whom were also providers. Of those identified as providers, the study participants estimated that each person was involved in anywhere between 10 and 100 home abortions. “That’s huge,” Ojanen-Goldsmith says. “There are potentially thousands of these abortions happening every year.”

Having or even soliciting a self-induced abortion, however, is illegal in Arizona and six other states—Delaware, Idaho, Nevada, New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina. Even in states without an outright ban, underground providers operate in, at best, a legal gray area. The Self-Induced Abortion Legal Team, which since 2015 has conducted research on self-induced abortion and the law, has identified about 40 types of legislation that could potentially be used to prosecute those who self-induce or help others do so. They range from murder and child endangerment to less obvious offenses, like failing to report a birth or improperly disposing of human remains. Because of the strong taboo against abortions, says SIA lawyer Farah Diaz-Tello, prosecutors may be more inclined to seek the harshest possible charges. And even outside the law, the work has plenty of critics, among them some abortion rights advocates who say this practice is medically or legally risky.

Some providers of clandestine abortions say that ending a pregnancy outside a clinic is akin to other forms of alternative health care like herbal therapies or home birth. And they believe the procedure represents a way for women to better understand their own bodies, especially their wombs, which are regarded with reverence. They see their work as a necessary effort to expand options for safe abortions. Many of their clients could go to a clinic but would rather terminate pregnancies on their own terms. As one secretive online resource for underground providers puts it, “Clinical abortion care plays a vital role,” but “we all deserve the right to choose how, where, and with whom we want to have our abortions.”

The familiar narrative of abortion access in America goes something like this: Back when the practice was illegal, women struggling with unwanted pregnancies sought out quack doctors for help, in some cases ending up blindfolded on strangers’ kitchen tables. By the mid-1960s, when between 200,000 and 1.2 million illegal abortions were performed each year, about 200 deaths from botched abortions were reported annually. Hospital wards were created specifically for women who developed infections or started hemorrhaging after trying to do it themselves. Then came the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision. Clinics with professional doctors sprang up to help women end their pregnancies safely. Abortion foes, led in part by Catholics, Moral Majority leaders, and conservative legislators, organized to fight “abortion on demand.” After the tea party’s 2010 victories in Congress and state legislatures, hundreds of new restrictions were passed in short order, forcing clinics to close and, researchers suspect, increasingly driving abortions underground.

Even pro-choice physicians stop short of endorsing underground providers, arguing that someone with inadequate training may not recognize complications.

Chloe Aftel

That story is true enough. But what’s also true is that for generations women have ended their pregnancies, successfully and without consequence, on their own or with the help of friends. In the early 1800s, when abortion was only illegal after the point of “quickening,” or discernible fetal movement (at roughly 16 to 20 weeks), women consulted medical guides with names like Domestic Medicine and The Female Medical Repository that described techniques for “unblocking obstructed menses,” such as quinine concoctions or cocktails of juniper and bitter apple. Herbalists and midwives offered teas made from the black cohosh root, a practice still in use today.

Later in the century, the newly formed American Medical Association spearheaded efforts to criminalize abortion, which historians believe was part of a larger campaign to monopolize the market and restrict competition, including from midwives. Physicians, almost exclusively men, publicly questioned the morality of abortion—and by extension the morality of the lay practitioners who provided it. Horatio Storer, a Harvard-educated “father of gynecology” and chairman of an anti-abortion AMA committee, wrote in an 1860s text that Anglo-Saxon American women should reject abortion to preserve cultural dominance. “Shall [America] be filled by our own children or by those of aliens?” Storer wrote. “This is a question that our own women must answer; upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation.” Still, abortion continued in the shadows. By the time the women’s liberation movement demanded a public reckoning with the private oppressions women faced, access to abortion had once again become a concern.

In the early 1960s, Carol Downer was a typist with four children at home and a marriage on the rocks. When she got pregnant a fifth time, she found someone who she thought was a doctor who agreed to give her an illegal abortion. He left wads of gauze in her uterus and a thin strip dangling from her cervix; in a later conversation, he said she could finally remove it. The material, hardened and dried with blood, felt like a sharp razor passing through her body, Downer, now 84 years old, told me. The experience radicalized her.

She joined the Los Angeles chapter of the National Organization for Women and, through a member of the group, met Harvey Karman, an abortionist whom she began shadowing. The first time Downer saw a cervix, she says, “I had an epiphany. It was just crystal clear the key role that ignorance of our bodies played in this whole situation.” If women understood their bodies and what the procedure involved, she reasoned, “we wouldn’t be sticking knitting needles into our uteruses and dying—or using douches of lye.”

Karman was pioneering a new way to perform abortions. Instead of scraping the lining of the uterus with a tool called a curette, a painful and invasive procedure, he used suction to remove the pregnancy. Downer and a friend believed this could revolutionize women’s ability to abort independently, eventually leading to the exclusion of intermediaries, like Karman, in the process. The biggest hurdle was the pelvic exam, which they practiced while using the suction technique to remove each other’s menses.

In 1971, after California, unlike most states, had liberalized its abortion laws, Downer’s group placed a notice in a Los Angeles newspaper announcing a meeting about reproductive health that was in fact intended to discuss Karman’s suction technique. Thirty women showed up at a bookstore in Venice Beach, but when Downer described freeing women to do abortions on their own, the crowd grew quiet. Sensing their worry, Downer lifted her skirt and hopped onto a desk, using a speculum and mirror to show the others how easy pelvic exams were to perform. “People were so happy, so interested,” she remembers. “They wanted to be a part of it.” The women began meeting weekly, and one of them figured out how to simplify Karman’s device with everyday materials including a mason jar, aquarium tubing, forceps, and a syringe to create suction.

Abortions were important, but the women also learned how to do pelvic self-exams and understand the biology of ovulation. Before long, Downer and another friend embarked on a tour to spread their self-help gospel to groups across the country. In California, hospitals had begun offering limited abortion services, and Downer’s group referred pregnant women to a physician at one of them while teaching self-help on other topics like natural contraception. But she also witnessed as many as 100 menstrual-extraction abortions outside clinical settings.

The implements used in a clandestine abortion

Chloe Aftel

Similar efforts were taking place all over the country. In Chicago, an organization of self-trained women called Jane offered abortions in the four years before Roe, ultimately terminating upward of 11,000 pregnancies, according to a book written by medical historian Leslie Reagan. A network of pastors and other religious officials created a nationwide referral service to connect women with safe, if illegal, abortion doctors. Outside the underground networks, feminist groups were pushing for better education about how women’s bodies work and a health care system that was more responsive to their needs, culminating in the 1973 publication of Our Bodies, Ourselves, a groundbreaking manual exploring all aspects of women’s health.

Within weeks of abortion becoming legal nationally, Downer opened a women-run clinic that offered instruction in self-help but where licensed physicians performed abortions. Years later, thanks to some of the tools her group pioneered, suction became standard practice for first-trimester abortions. But her greatest legacy may be her role in reviving the community health care traditions in which women helped other women. “We hearkened to the message that women need to take back our health care,” Downer says, to “regain female knowledge” of reproduction.

Sitting across from me on a bench in the secluded corner of a coffee shop in Arizona, Renata, who grew up in California’s Central Valley with Mexican immigrant parents, describes her work with clients. Typically with no other options, always referred by word-of-mouth, they call her by a code name that she didn’t want to share with me. Establishing trust works both ways; Renata vets them thoroughly, since she must be sure they won’t turn her in to law enforcement. She explains worst-case scenarios, backup plans, and, should complications arise, the necessity of telling an emergency room physician that they might be having a miscarriage. For most of her clients, their income level and immigration status make health insurance impossible and hospitals and clinics intimidating. (Renata charges clients on a sliding scale and often collects about $25, which means she’s typically losing money.) “It’s hard enough to set foot in a school, let alone a hyperformal clinic,” she says. Even though many clinics also charge on a sliding scale, her clients are often fearful of leaving “a paper trail,” not having an ID, or encountering language barriers. All they want is a safe and effective way to end their pregnancies.

Usually, Renata gives them misoprostol, one of two drugs for what is known as a medication abortion. In clinics doctors tell patients to take mifepristone first, to end the pregnancy, and then misoprostol to expel it from the body. But in the 1980s, women in Latin America realized that misoprostol, otherwise known as miso, was effective on its own. Even more appealing, miso is cheap and widely available, since it’s also used as an anti-ulcer drug. A friend with a medical license sends Renata the drugs and she gives them to her clients, often supplemented by a regimen of herbs. She sits with them during the abortion, which can take a full day, and follows up regularly once it’s done. After the procedure, Renata destroys all the client’s records.

It’s unclear exactly how many people have been prosecuted for helping someone end a pregnancy. Before abortion was legalized, police raided two apartments where the Janes worked in 1972. Three women waiting for abortions were taken to the hospital, and seven Janes were arrested, including a high school English teacher, several stay-at-home mothers, and a student. One of the providers swallowed a list of patients’ names she carried in her purse. All seven were referred to a grand jury for indictment, but the case was dismissed when the Supreme Court legalized abortion. That same year, police raided Downer’s self-help clinic in Los Angeles after someone reported that she had treated a yeast infection by inserting yogurt into a woman’s vagina. She was arrested and charged with practicing medicine without a license, which she beat by arguing that her home remedy was not, in fact, medicine.

More recently, women who weren’t affiliated with the at-home abortion movement have been prosecuted. In 2012, Jennifer Whalen, a 36-year-old mother of three in rural Pennsylvania, where about 85 percent of counties are without an abortion clinic, ordered abortion drugs online for her 16-year-old daughter. The closest abortion clinic was 75 miles away, and the procedure would cost up to $600. After taking the drugs, her daughter got scared, so they drove to the ER, where staff reported Whalen to child protective services. Her daughter was fine, but nearly two years later Whalen was charged with a felony for offering a medical consultation without a license, and with three misdemeanors: endangering the welfare of a child, dispensing drugs without being a pharmacist, and assault. She pleaded guilty to the felony and one misdemeanor and was sentenced to 9 to 18 months in jail. In 2015, an Arkansas nurse gave drugs to a friend who ended her pregnancy at home before going to the emergency room, according to an incident report. Her friend was reported to law enforcement and later was convicted of concealing a birth; the nurse ultimately pleaded guilty to unlawful abortion.

Since 2015, Renata, a clandestine provider in Arizona, has helped about 20 people end their pregnancies.

Chloe Aftel

Renata and the other providers I interviewed are terrified they could end up in the same predicament. One woman, based in a Western state, who has helped about 150 women—many of them sex workers—end their pregnancies said she constantly rotates through burner phones to stay under the radar. When I asked her how she stays safe, she replied half-jokingly, “My partner has a lot of guns.” She wrote to me shortly after her second child was born: “I know that I am putting myself and my family at risk for being without me if I am prosecuted or worse. I do this work to help people who need it.” In California, I spoke to Ruth, another provider who started performing at-home abortions after finding the clinic experience to be too sterile and isolating. “Staying at home, choosing who is with them and who is not, gives people autonomy,” Ruth said.

But doctors are skeptical that self-induced abortion is a safe option. I talked with a Planned Parenthood abortion physician—one of just a handful in Arizona—who asked to remain anonymous to protect his identity and his family’s safety. He’s not surprised more women aren’t making it to his clinic these days. Over the last decade, Arizona has passed extremely restrictive abortion legislation. One law stipulates that surgical abortion can only be performed by a physician; a second law forbids physician assistants from dispensing abortion drugs. In 2008, there were 10 Planned Parenthood clinics that provided abortion services. Now, there are only four. Plus, patients face mandatory waiting periods and parental consent laws.

The state has also passed strict regulations of abortion by medication. In March 2016, new guidelines from the Food and Drug Administration recommended that mifepristone could be used until the 10th week of pregnancy and at lower doses than previously thought. But a day later, Republican Gov. Doug Ducey signed a bill requiring Arizona doctors to use the outdated protocol, forcing women to undergo a less effective regimen with more side effects. (That measure was subsequently repealed.) The state has banned physicians from prescribing abortion drugs by phone, so women may have to drive hours for an initial mandatory counseling appointment before sitting out a required 24-hour waiting period and returning for their prescription.

RELATED: She Was Desperate. She Tried to End Her Own Pregnancy. She Was Thrown in Jail.

The Arizona doctor says that over the last two years, the number of patients who have asked him about self-induced abortion has skyrocketed. He regularly Googles “self-induced abortion,” so he has some sense of what his clients might be seeing, but he is ultimately skeptical about its safety for every patient. Women come to him with complications. “I ask myself, ‘Is this something I’d want my daughter to do?’ And the answer is no. But the reality is I can understand.”

Daniel Grossman, a prominent abortion rights expert and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California-San Francisco, notes that research does support some methods of self-induced abortion. “I don’t believe self-induced abortion is necessarily unsafe,” he says when I reach him by phone. He adds that women can “very safely” take misoprostol on their own. But as a physician, he can’t ethically recommend that they use menstrual extraction kits and other such devices to end their pregnancies. There’s a risk of uterine perforation and hemorrhaging, which can be deadly. The safety of these methods depends on the provider, he says, and someone with inadequate training may not know when there’s a complication. As for the herbs, which are believed to flush out the contents of the uterus, like miso does, Grossman says their safety and efficacy haven’t been proved.

Even Heather Booth, the founding member of Jane who ran an underground abortion service out of her dorm room at the University of Chicago and describes her cause as a righteous “good deed,” stopped short of saying she approved of what Renata and her colleagues are doing. When I asked if she still saw a need for underground abortion, she demurred. “I think we need to do everything possible to make [abortion] available to all and ensure that the services are available for all.”

All the underground providers I spoke with rejected the notion that the care they provide is unsafe. Many harbor a deep dislike of the medical establishment and are convinced their work will always be criticized because doctors see out-of-clinic care as a threat to their monopoly. As with Downer and the 19th-century midwives, they seek to provide a different type of care entirely.

As part of her study, Ojanen-Goldsmith asked participants who had previously self-induced, some of whom were also providers, why they did it. Nearly two-thirds had had at least one clinical termination prior to their self-induced abortion, and more than half had worked or volunteered in traditional settings. They self-induced either to avoid a clinic—perhaps because of an onerous restriction or affordability—or because they wanted something like an herbal regimen, a spiritual ceremony, or the comfort of their own homes. Diaz-Tello notes, “It’s not all out of desperation.”

Renata knows this all too well. She recently helped a transgender man, a citizen who could have afforded Planned Parenthood but didn’t feel comfortable there, end his unwanted pregnancy. As for safety concerns, she points out that she always discusses them with her clients but adds that no one has ever been deterred. “They know they have no other options,” she says. “People are fucking terrified of continuing their pregnancies.”

On a blazing hot summer day last year, Renata shows me into the two-bedroom red-brick house she shares with her boyfriend. A pit bull greets us, and sitting on an entryway table is a speculum decorated with rhinestones and feathers. They had recently moved into the house from a smaller one-bedroom apartment so that Renata could see clients in the extra room.

Renata’s sister is her only family member who knows what she does. She is alone in her shadowy work, and in more ways than one—she has met just a handful of providers of color on the job and worries that, because most of the underground providers she knows are white, women of color who need help ending a pregnancy might hesitate before contacting them. She hopes more Spanish speakers and people of color will get trained to provide at-home abortions, but until then, she’ll do what she can. “You create a system when the need is high enough.”

One of her clients is Sofia, a botanist in her 20s who was seven weeks pregnant when Renata gave her misoprostol last October. Someday, Sofia plans to have children with her current partner, but this pregnancy came as a shock. She had immigrated to the United States from Mexico as a small child and was undocumented until recently. She decided she just couldn’t afford a baby. “I want to make sure that I’m at a better place in terms of finances when I do have a child,” she says softly over the phone.

Her experience as an undocumented immigrant—living most of her life under the radar and without health insurance—and her traumatizing memories of navigating a hospital system unsympathetic to Spanish speakers, plus the expense, made her wary of what she might face in a clinic. So, she found Renata. “I knew that if I was going to do this, I had the choice and the option of doing it at home,” she tells me before breaking into tears. “I haven’t told people in my homeland. It’s stigmatized. There was never the option to have an abortion.” With the help of herbs and miso, Sofia successfully ended her pregnancy.

“Renata is a role model in the way she supported me through this,” Sofia says. “It takes a special kind of person to do this work, especially to do this underground, without people knowing much.”

This article has been updated.