mediaphotos/Getty

If you’re locked up in Texas and want to earn a master’s degree, you’re out of luck unless you have a penis. That’s right: Although the state incarcerates more women than any other, its prison system denies female inmates access to educational programs offered to men, according to a startling new report by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition.

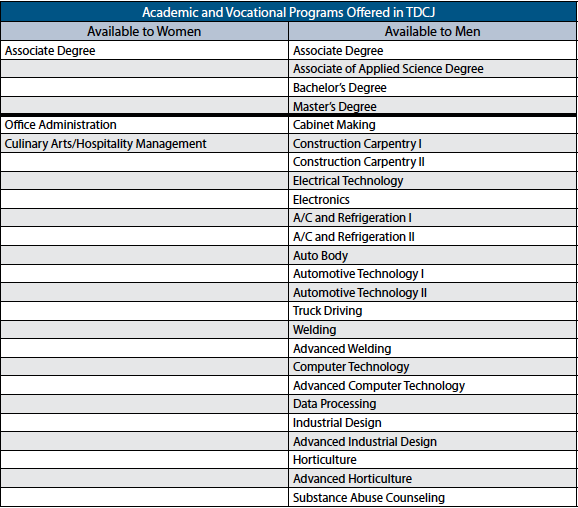

The report was released Tuesday and points out several jaw-dropping disparities in educational programming: It says men in Texas state prisons can get vocational certificates for 21 occupations, ranging from computer technology to cabinet-building, while women can only earn certification in two—office administration and culinary arts/hospitality. According to the report, male and female inmates can both take courses through the Windham School District, but men can choose from 48 courses and women only get 21.

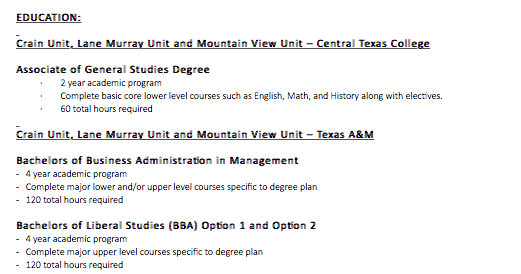

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) has since slammed the report as “a significant mischaracterization of the facts,” arguing that the allegations about certification programming are “simply not true.” The report states that female inmates are limited to associate’s degrees. Jeremy Desel, a spokesman for the Department of Criminal Justice, acknowledged that women inmates in Texas state facilities can’t earn a master’s degree. But he said prisoners at 3 of the state’s 15 facilities for women can earn bachelor’s degrees in business administration and liberal studies from Texas A&M University.

The report’s author, attorney Lindsey Linder, says the data she cited came straight from the department itself, as well as from Windham School District. “I reported everything they gave me,” she says, referring to information from the corrections department. She added that the department had an opportunity to review the entire report before it was published.

“The master’s degree program for men is offered at a single unit that’s in close proximity to an educational institution,” says Desel by way of explanation about the disparities. “The majority of our women’s units are all in the same geographic area—that may be part of the issue.”

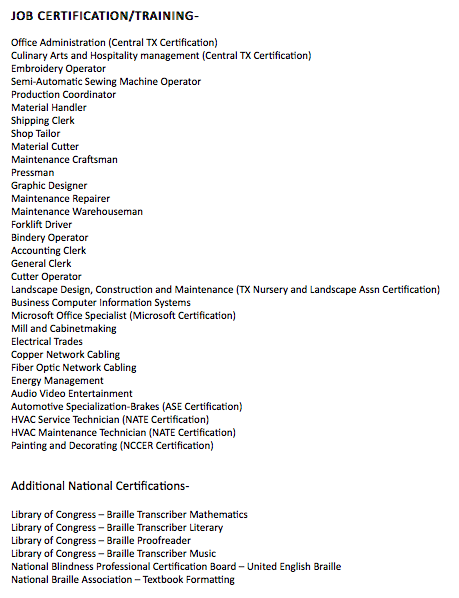

In contrast with the report’s findings, he added that women can get certification or training in more than 35 vocational occupations ranging from embroidery and sewing-machine operation to cabinet-making. He could not immediately comment on the number of certifications offered to male inmates. “Certainly we are active in doing our best as an agency to make sure there are as many programs and possibilities educationally, vocationally, and otherwise for women, men, and the entirety of the offender population,” he added, noting that the agency recently created a new position to focus on those issues.

When I asked Linder about the claim that geography might limit educational access for women, she wasn’t immediately convinced. “You can get all manner of degrees online, so I can’t imagine there aren’t programs that would be accessible through telecommunication,” she pointed out. When I told her the Department of Criminal Justice said dozens of certificates were available to women, rather than just two, she reiterated that the department reviewed the statements in her report before publication. She says she met personally with the department’s executive director, Bryan Collier, and his team, and that she incorporated their feedback into the final study. “They raised no concern with the certification programming we reported,” she adds.

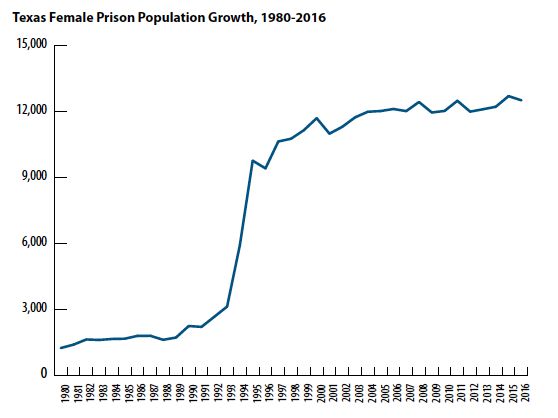

While men outnumber women in Texas state prisons, female inmates are a quickly growing population: Their numbers increased more than 900 percent from 1980 to 2016, compared with a nearly 400 percent increase in male prisoners. Most women in the system are locked up for nonviolent crimes, according to the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, and about two-thirds of them have not completed high school, while more than half were living below the federal poverty level at the time of their offense.

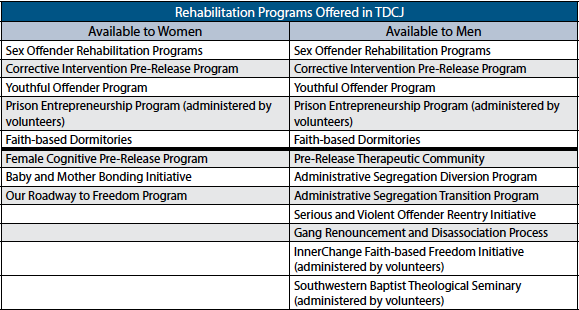

The coalition’s report found that state prisons offer more rehabilitation programs to men than to women, a claim that the Department of Criminal Justice spokesman was not able to immediately confirm or deny on Tuesday. “Women deserve to have equal opportunities to these programs,” says Linder. “Without equal access to educational vocational programs, they don’t have the same opportunity to succeed.”

Here’s more information from the coalition’s report and from the Department of Criminal Justice’s spokesman. The first two tables show the report’s account of programs offered by gender. The second two lists show the department’s account of educational and vocational programs for women.