Becki Sarnicky, who lost her son Nick, at her home in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in January

Bryan Anselm/Redux for Mother Jones

The offer was too good to resist: Go to rehab for a week, get $1,000 in cash. It was early 2017, and Brianne, a 20-year-old from a woodsy Atlanta suburb, had come to South Florida to leave her heroin addiction behind. At a residential facility called Recovery Villas of the Treasure Coast, she was approached by a charismatic guy I’ll call Daniel, a Pennsylvania native six years her elder. He could relate to her troubles—he’d struggled with addiction himself—and he could get her into another rehab after Recovery Villas. He would even pay her: $1,000 for the first week of her stay and $500 each week thereafter. That money could buy Brianne a whole lot of heroin.

Brianne, whose full name has been withheld to protect her privacy, could be a poster child for the opioid crisis: a blond, green-eyed former softball star who experimented with pills from the medicine cabinet with her high school boyfriend and within a few years was plunging needles into her veins. In 2016, she broke down and admitted to her mom, a software executive named Jen, that she needed help. They made a plan: Brianne would go to treatment for a few months, sober up, and then return home to study at Chattahoochee Technical College.

Listen to reporter Julia Lurie detail her nine-month-long investigation into how rehab brokers are trapping some opioid users in a vicious cycle of dependence and exploitation, on the latest episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

That never happened. Brianne took Daniel up on his offer and, over the next 18 months, did more than a dozen stints at Florida rehab centers from Palm Beach to Miami. She mainly flitted between Recovery Villas—which in addition to group therapy and 12-step meetings offered apartment housing and a pool—and Compass Detox, which felt like somewhere between a hospital and a hotel.

Sometimes, between stays, Daniel rented a room for Brianne and a few other “clients” at a Super 8 or Comfort Inn and supplied them with heroin and the overdose reversal medication Narcan, just in case. When the drugs ran out, Brianne would head into a detox program with dirty urine, an admission requirement for some facilities. Other times, she coordinated directly with rehab staffers who called her “honey” and “sweetie” and arranged free transportation—Ubers, flights if need be—to their centers. Daniel encouraged Brianne to try her hand at recruiting: For every patient she steered his way, he would pay her $400. After she started dating a recovering user who lacked health insurance, Daniel found rehabs that would take her boyfriend for free as long as Brianne attended with her Aetna insurance card, a practice known as “piggybacking.”

The addiction community has a name for what happened to Brianne. It’s called the “Florida shuffle,” a cycle wherein recovering users are wooed aggressively by rehabs and freelance “patient brokers” in an effort to fill beds and collect insurance money. The brokers, often current or former drug users, troll for customers on social media, at Narcotics Anonymous meetings, and on the streets of treatment hubs such as the Florida coast and Southern California’s “Rehab Riviera.” The rehabs themselves exist in a quasi-medical realm where evidence-based care is rare, licensed medical staffers are optional, conflicts of interest are rampant, and regulation is stunningly lax.

While experts say the practices described in this story are widespread, it is important to note that there are plenty of responsible treatment providers, and not all the facilities named engage in all the practices described. Recovery Villas, which was raided by Florida authorities last summer on suspicion of insurance fraud and is now under investigation by the state, did not respond to my questions. A Compass Detox spokesman said that paying clients for treatment and giving them drugs between rehab stints “is illegal and we don’t do that.” Compass obeys all relevant laws and regulations, he emphasized.

RELATED: Finding a Fix: Embedded With the Suburban Cops Confronting the Opioid Epidemic

Drug addiction rates have skyrocketed over the past decade: If every American addicted to opioids lived in one city, it would be nearly the size of Houston (pop. 2.3 million). The demand for treatment, the increasingly white face of addiction, and recent laws requiring insurers to cover substance use services have all resulted in a surge in rehab spending and private investment. But as the Braff Group, which tracks health care trends, warned investors in a 2014 brief, “It’s not all kittens and rainbows. As we have seen countless times in other frenzied health care sectors, when the money flows in, so do the ne’er-do-wells, which can bring the sector the kind of attention it doesn’t want.”

It’s a given in the world of addiction treatment that relapses are likely obstacles on the road to recovery. But for rehab owners and brokers who make money each time a patient is admitted, relapses can be a profit center. Dozens of drug users and parents I spoke with had tales like Brianne’s, and “there are probably thousands” of others, according to Karen Hardy, a Maine addiction counselor whose own son shuffled among dozens of rehabs. “Some end in death. Some don’t,” she says. “It’s Russian roulette.”

For Jen, Brianne’s recovery saga has been a nightmarish roller-coaster ride. At work one morning in June 2017, she received a text from an unrecognized number that made her blood run cold: “I OVERDOSED CALL ME NOW.” Over the phone, Brianne frantically explained she was at a hospital near Palm Beach after overdosing for the first time—in a motel room, with heroin provided by Daniel. There were more panicked calls that summer: Brianne at a gas station, without shoes, money, or transportation. Brianne bawling after yet another friend overdosed. (She lost 15 friends in a single year, Jen says.) The sounds of sickening shrieks and thumps as her boyfriend flew into a violent rage. Brianne overdosing again. Back home, her 13-year-old sister filled an Ugg shoebox with prayers jotted on slips of paper, begging God not to let Brianne die.

The amounts billed to Jen’s insurance company seemed outlandish: $3,000 for a routine drug test and, in one case, $22,000 in rehab charges in a single day. (Residential rehabs often charge private insurers $50,000 to $100,000 per month of treatment.) Jen begged her daughter to come home, and sometimes she would, crashing in her childhood bedroom for a few days. But Brianne’s boyfriend would inevitably show up while Jen was out, or a recruiter would offer a free flight back to Florida and Brianne would disappear again. On one road trip south in 2017, Brianne took the wheel while high. She was pulled over by a Georgia state trooper and charged with a misdemeanor DUI, which earned her a night in jail, probation, and community service. Jen began compulsively checking her daughter’s cellphone location and reading her texts. Where was she today? Jen wondered. A treatment center? A halfway house? A morgue? Brianne half-jokingly referred to her mom as “the FBI.”

In the standard narrative of the opioid crisis, greedy pharmaceutical companies are the villains and kids like Brianne are the casualties. But now we are in phase two, an addiction epidemic compounded by a treatment network that in many cases sets patients up for failure. Where pill mills proliferated a decade ago, unscrupulous rehabs sprout today. “A lot of the talk until this point has involved more money for rehab,” says Dave Aronberg, the state attorney for Palm Beach County, one of the few jurisdictions that has vigorously pursued lawbreaking treatment providers. “Little has been said or done on the issue of patient brokering and insurance fraud that has cost so many lives.”

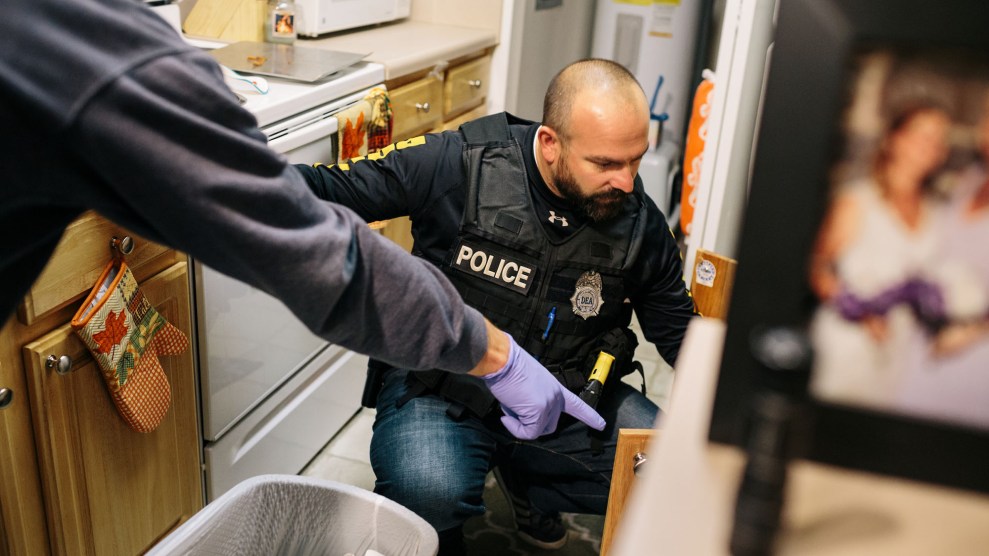

A handful of states have outlawed the worst practices, most notably Florida, which in 2017 made it a felony to give or receive kickbacks for referring patients to drug treatment. To date, Aronberg’s local task force of 12 investigators and two full-time prosecutors has charged 66 people with patient brokering and insurance fraud. Last fall, Congress passed the Eliminating Kickbacks in Recovery Act, a law similar to Florida’s, but so far the Justice Department has yet to indict anyone.

With oversight wanting, it’s hard to say what proportion of rehabs engage in predatory activities. “When I started looking at this two years ago, I thought the abuses were abnormalities—they were fringe players,” says Doug Tieman, CEO of Caron Treatment Centers, one of the nation’s largest rehab providers. “One of the things that I found was that there was an incredible amount of ignorance regarding the law.” Some operators take advantage of the lax oversight, he says. Others mean well but are ignorant of best practices. “Out of 100 facilities, less than half are playing by the rules” when it comes to marketing, recruitment, and insurance, estimates a billing agent who has worked with dozens of Southern California rehabs.

Lately, Aronberg’s team has noticed that when it shuts down a facility in Palm Beach, the owners simply open a new one in a state with weaker enforcement. “These are innocent people with a substance use disorder lured to Florida under false pretenses, only to leave in an ambulance or a body bag,” Aronberg says. “And now this has spread to the rest of the country.”

In the winter of 2017, Brianne returned home after a messy breakup with her boyfriend and holed up in her bedroom. The breakup seemed to have flipped a switch: Brianne was a wreck, but she was intent on avoiding drugs. As months went by, things inched toward normal. She looked for work, went to her sister’s basketball games, and watched horror movies with Jen. It was the longest she hadn’t used in years. “We’re working on applying for jobs and interviewing,” Jen told me last May. “It’s like you have to catch up.”

But all the while, Brianne had been exchanging Facebook messages with brokers who asked how her sobriety was going and offered rehab spots in seaside destinations. Last June, Elan, a patient broker from Long Island, messaged that he could get her into Compass, the Florida rehab she’d attended several times before. “I can fly u down and shit,” he wrote. “I have a really good relationship with the owners I promise you they won’t call ur mom.”

In an ideal world, sobriety builds upon itself—each drug-free day with family and friends adds to a reservoir of resolve to draw on when things get tough. But at 21, Brianne was sick of living in a childhood home that brought back bad memories and felt demoralized by her lack of progress toward independence. She slept the days away and watched TV into the wee hours. “Just kinda giving up at this point,” she responded to Elan. Days later, she told Jen she was going to a friend’s house. Instead, she bought some Xanax off the street—to make sure she had dirty urine—and boarded a plane to Fort Lauderdale.

Back home, Jen frantically researched Compass and learned that its medical director’s license had been put on probation in 2006 after he prescribed hundreds of opioid painkillers to co-workers at a previous job without giving them physical exams. (“The Florida medical board dealt with it, and he’s currently licensed and active,” said the Compass spokesman, who declined to comment on Brianne’s case.) When Brianne arrived at the facility, she later told Jen, she was prescribed Klonopin, a benzodiazepine, and Suboxone, an opioid used to stave off cravings for more potent narcotics, even though she hadn’t used opioids in months. (The Food and Drug Administration warns against mixing opioids and benzodiazepines, both of which can impair breathing.) When Jen managed to get her on the phone, Brianne spoke with slurred words, her tone flat. On Facebook, meanwhile, Elan was posting updates such as “Smile & dial,” and “Anyone a beast on the phone n wanna come work, 25% on everything you close!!!! PPO not required!!”

“I don’t know if I’m going to be able to get my child back,” Jen told me in July. “That entire environment down there is lethal. That’s the only word that I know to use.”

Around this time, Barbara, an engineer from New Jersey, was sending me real-time texts after a broker flew her 22-year-old son, Ben, to the West Coast and supplied him with drugs before sending him to detox. (Both names have been changed.) “Last i heard from him he was at [the] airport,” she messaged. “i’m pretty worried this time. he has no meds and he has seemed a lot less stable lately.” Barbara reached out to the brokers and demanded they stop contacting her son, who at one point had told her, “‘Mom, when they look at me, they see dollar signs.’”

Sarnicky holding a photograph of her son Nick

Bryan Anselm/Redux for Mother Jones

I was also in touch with Becki Sarnicky, a Pennsylvania nurse desperately trying to figure out what had happened to her son. Nick, 23, had left an electrician training program and a girlfriend of three years to attend rehab in Los Angeles in late 2017. He had gone through four rehabs in five weeks, racking up insurance charges in excess of $100,000. Between stints, Nick had texted Brad, his patient broker, to give him insurance information and ask for some black tar heroin. Brad, in fact, was the last person he ever texted. Police found Nick’s body one morning that December on the floor of a motel room in Los Angeles. According to the police report, he was scheduled to go into detox that very day.

Sarnicky is clear-eyed about her son’s ordeal. “I respect Nick enough to know he’s not a victim totally,” she says. But “when your recovery system and the people that are referring you to a rehab are getting you drugs, it’s so broken and backward.”

For most of the past century, addiction was considered not a medical problem, but a personal moral failing to be solved by jail time or “abstinence-based” programs. Alcoholics Anonymous, the pioneering treatment program founded in 1935, teaches sober living through faith, responsibility, and environmental changes. AA tapped into a critical need for support among people struggling with addiction: By 1950, it boasted nearly 100,000 active members. The 12-step ethos gave rise to a larger ecosystem of abstinence-based, mom-and-pop rehabs—often in inviting destinations like Palm Beach or Malibu, California—where people with drug or alcohol problems could go for a few weeks or months to get sober.

A huge change came about in 2008: Based in part on a body of evidence showing that addiction has neurological underpinnings, Congress passed legislation requiring private insurers to offer the same benefits for mental health and addiction treatment as they do for other medical services. The Affordable Care Act, rolled out in 2014, codified mandatory drug treatment coverage and allowed young adults, who have the highest rates of substance use disorders, to stay on their parents’ insurance until age 26. “We knew that if there was anything [the ACA] would help a lot for, it’s addiction,” said Keith Humphreys, a former drug policy adviser to President Barack Obama. Roughly 3 million people with substance use disorders gained coverage, and from 2011 to 2015, private insurance spending on patients with opioid addiction grew tenfold, to $722 million a year, according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit that tracks insurance claims.

Wall Street took note. In 2014, a rehab chain called American Addiction Centers went public on the New York Stock Exchange, attracting investments from the likes of Morgan Stanley and BlackRock. Mergers and acquisitions related to drug and alcohol addiction programs doubled between 2013 and 2016, according to the Braff Group, and 48 private equity firms entered the market over the last five years. With more people heading to rehab and more money to pay for it, “the investment community noticed,” says the group’s president, Dexter Braff.

All this activity has funneled billions of dollars into an addiction industry dominated by small providers that are mostly disconnected from traditional medical institutions. The roughly 14,000 licensed addiction treatment facilities in the United States each serve, on average, fewer than 100 patients at any given time. They include detox centers, where patients go to agonize through withdrawal; residential facilities, where patients stay a month or more as they receive treatment and attend group meetings; and outpatient facilities, whose patients tend to live in group sober homes and go to classes and appointments during the day.

Overdose fatalities are soaring

Deaths

Money is pouring into addiction treatment

Private insurance claims for opioid users (millions of dollars)

And for-profit providers are increasing their market share

Rehab attendance (thousands)

The programs vary wildly in approach. Some specialize in equine therapy or music therapy. Some resemble doctors’ offices, others flophouses. And while numerous studies show that access to addiction medications dramatically improves recovery prospects for people addicted to opioids, only about one-third of treatment programs offer any of the three FDA-approved drugs. Fewer than 2 percent offer all of them. (Reasons include licensing issues, spotty insurance reimbursement, and an aversion to using drugs to get patients off other drugs.) Programs such as Narcotics Anonymous work wonders for some people, but more often they fail. By some estimates, more than 80 percent of people who attend abstinence-only programs relapse.

Drug policy experts often wryly point out that the basic rules of medicine don’t seem to apply to addiction treatment. Many rehabs don’t employ a single licensed doctor. “Imagine trying to license a clinic or a hospital and saying, ‘We have zero doctors or nurses,’” says Humphreys, the former Obama adviser. As of 2012, only six states required addiction counselors to have a bachelor’s degree, according to a report from the Center on Addiction. “The regulatory requirements for nail technicians are higher in many states,” says Emily Feinstein, the center’s executive vice president. In California, which has among the nation’s loosest rehab regulations, aspiring counselors must do little more than complete a nine-hour orientation (good for five years) before working in state-certified treatment centers, and anyone can open a sober home just by hanging out a shingle.

The federal Stark Law limits the ability of physicians to own diagnostics companies related to their specialties—generally speaking, doctors can’t have a stake in outside blood-work labs or imaging companies to which they refer patients—but the law does not apply to addiction treatment. Rehab operators can own urine-testing labs, order multiple tests per week for each patient, and charge insurers hundreds of dollars a pop.

One in five rehabs boast a seal of approval from the Joint Commission, an organization that accredits medical facilities, ensuring they are clean, safe, and well staffed. The seal implies quality, but the commission is perfectly willing to accredit abstinence-based rehabs that discourage the use of proven addiction medications. “It would be like giving a cancer center accreditation because they have licensed physicians and exit signs over the doors, but they only treat cancer with grape juice or meditation,” says Samantha Arsenault, a director at the treatment advocacy organization Shatterproof. A spokeswoman for the commission acknowledged in an email that “we are not prescriptive as to the modality of treatment.” The commission doesn’t regulate recruiting and business practices, either. Some of the rehabs raided by Florida authorities—including one owned by Kenneth Chatman, who was sentenced to 27 years in prison for committing health care fraud and coercing patients into prostitution—were certified until the day they shut down. The Joint Commission is “not a public or regulatory agency,” the spokeswoman noted.

Insurers, in the meantime, are stuck playing whack-a-mole: “These programs are pretty difficult to keep up with,” says Ken Duckworth, medical director for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “Places may change their names, labs may change, that sort of thing. It’s not just one target.” Insurance companies’ provider networks sometimes include drug treatment programs that don’t offer evidence-based care, but at the very least such programs are vetted. Several experts told me practices such as overbilling and patient brokering are more common among out-of-network rehabs, which often attract patients and family members via TV ads, social media, and online addiction forums.

Perhaps the most insidious difference between the rehab and medical worlds are the backward care incentives. When a hospital consistently delivers low-quality care, resulting in the readmission of patients, that hospital may be penalized by insurers. Not so with addiction treatment: “If I’m a Malibu rehab, I get to bill the insurance company when you come,” says Greg Williams, executive vice president of the nonprofit advocacy group Facing Addiction. “Then when you come back, I get to bill the insurance company again. But if you stay well, I get nothing.”

While reporting this story, I’d collected countless accounts of the rehab shuffle but had little insight into the mind of a patient broker—until Peter called to set the record straight. Peter, not his real name, told me he’s 22 and probably one of the “top five” brokers in Los Angeles. He’d heard I was poking around, so he phoned me out of the blue and we talked for hours. He views himself as a mashup of a caseworker, a hustler, and a friend, advising parents on the best rehab options, coordinating travel, and helping addicts get clothes, food, hotel rooms, and cash if need be. “I will set everything up for u and have u on a flight out as soon as your ready,” he wrote to a potential client on Facebook in February 2018. I can see why Peter is good at his job: He’s disarming and reflective, and he knows the regulatory landscape. He used to work in South Florida but moved to Southern California after Florida lawmakers cranked up the heat. He suggested, but would not say outright, that he works for a company of patient brokers—“marketers,” he called them—that contracts with rehabs.

Peter insisted he has the patients’ best interests in mind. “It takes a lot to help an addict get into recovery,” he said. “Sometimes you spend days and nights trying to help this person.” He is paid $5,000 to $12,000 for each client admitted, which breaks down to about $500 an hour—too good to resist, in his view: “We’re being lured by the treatment centers, and the clients are being lured by us.”

He’s in recovery himself. Just over a year ago, Peter was arrested after police caught him with a backpack containing heroin and needles. Sometimes, the angry Facebook messages he receives from parents—accusing him of profiting from addiction or of being a “child killer”—make him want to use again. He concedes that people should probably be trained in order to do what he does, and that the cash incentives create conflicts. But “what did you expect when they decided that we’re just gonna put no laws in place and let a bunch of drug addicts help other drug addicts?” he said. “It’s like the wild, Wild West out here.”

Some rehabs use their own patients to recruit. “Just about every treatment center I went to had me do it,” says a 35-year-old Wisconsinite who cycled through 27 residential treatment stays, mostly in California and Florida. She found her clients on Facebook, at support groups, even at Walmart, and as she recruited them, she knew others were trying to recruit her: “A lot of times, I have felt like a body with a price tag.”

It’s easy for unwitting patients to be roped into brokering, says Sam Bierman, executive director of the Maryland Addiction Recovery Center. “You see a young guy pull up, and he’s in a Mercedes and he’s got Michael Jordan sneakers and he says, ‘What if I gave you $70,000 a year and all you have to do is get as many people into treatment as possible? Help curb the opioid epidemic,’” Bierman says. “It’s this cyclical chain. It’s really awful to watch.”

RELATED: Children of the Opioid Epidemic Are Flooding Foster Homes. America Is Turning a Blind Eye.

Brokers aren’t the only way to bring in patients—there’s also good old corporate marketing. The publicly traded American Addiction Centers, which boasts dozens of facilities across nine states, owns more than 100 websites, founder Michael Cartwright explained during a 2017 health care conference presentation. “If you type in ‘heroin addiction’ or ‘methamphetamine addiction,’” he said, “you’re probably going to come across one of our websites.” These sites include rehab referral platforms such as Recovery.org and Rehabs.com. Up until last summer, when a US House of Representatives subcommittee pressed Cartwright on the matter, those home pages made no direct mention of AAC’s ownership—only by clicking on a “Who Answers?” link next to a hotline number would a visitor learn that the lines were staffed by AAC reps. Cartwright told me he thought the ownership was apparent enough, but AAC made it more prominent because “we wanted to be 100,000 percent clear.”

As of 2017, the company also had 65 sales reps promoting its services to emergency rooms, doctors, therapists, and DUI attorneys: “Think of them like pharmaceutical reps calling on referral sources, and they are all over the country,” an AAC executive told industry professionals that year. “We are a health care company, but we are also a consumer marketing company.” Roughly 30,000 calls per month came into AAC’s Tennessee call center, where “we have 100 sales reps answering the phone,” Cartwright said in 2017. (He prefers to call them “navigators,” he later told me.)

Another recruiting tactic is to appeal directly to the mothers of young people struggling with addiction. This was a specialty of Amethyst Recovery, launched in 2014 by a recovering drug user named Ian Treacy. Amethyst runs two Florida facilities and has a stake in a new Maryland rehab, and until recently it was involved with a program in New Hampshire. Treacy was “a Facebook guru with all these moms,” according to a former patient who says Treacy enlisted him to approach potential patients on Facebook groups such as The Addict’s Mom (now 34,000 members), Heroin Support (49,000 members), and A Mothers Hope (14,000 members)—a group Treacy himself created. “You message them like a leech,” the former patient told me.

Mother Jones acquired a screenshot of a 2016 text exchange between two Amethyst marketers offering services to a mother who’d posted in A Mothers Hope. The mom had indicated she was a federal worker, leading one of the marketers, Corey Hassett, to speculate she had a Blue Cross Blue Shield policy. “I’m moving in on the kill ally,” he texted his co-worker. Ally replied that she’d reached out again, and that Hassett should feel free to do the same: “I hit the bitch again since she didn’t answer. Corey I didn’t get anything so while I pissed on that hydrant it’s not mine.”

In this text exchange, two rehab marketers traded notes on a prospective client.

In another exchange, Ally texted Treacy, “Just spoke with a woman who paid 40k for her granddaughter to go to rehab for 1 month and of all places fuxking [sic] Texas.”

“Lol,” he texted back. “Tell her to take her out and we will charge 20.”

“My mindset was, we provide just as good a care at half the cost,” says Treacy, who left Amethyst in 2017 and now heads up business development for another Florida rehab. He disputes the notion that there was anything predatory about Amethyst’s approach. “Our policy since before Amethyst opened was to find placement for each and every individual that came across our paths no matter the financial status of the family,” he says. And while the company’s growth hinged on social media outreach, its employees were properly trained—“it’s not just like we’re hiring you to scour Facebook pages,” Treacy says. Social media “was just easy access for the parents to reach out to us. There was a need for them to have support.”

Ally, who no longer works in the recovery field, acknowledges that her language was unprofessional. “Now I’m a mother of two, and I don’t refer to everyone as bitches,” she told me over the phone. But at the time, “I’m this homeless drug addict that got clean and was offered a chance.” She said she went through 23 rehab programs before her mom learned, on Facebook, about a Florida treatment center that turned her life around, and that she is proud of having helped dozens of people find treatment—some still send Christmas cards and recovery updates: “My only intention was to help other people in a similar position to me.”

Hassett, the other marketer, now directs community outreach at the Freedom Center, Amethyst’s sister facility in Maryland. He “does not participate in wrongful social media practices, and [his] only mission is to better his community and fight against the opioid epidemic,” an Amethyst spokeswoman said in an email. She added that recruiting clients on social media is “against company policy,” and that “every outreach and admissions employee undergoes extensive legal and ethical training.” The company’s Facebook efforts, Treacy told me, were a mixed bag: “We provided very good care, but if someone had a bad experience it was slandered across social media. We were in the public eye.”

Karie Dove, an Oklahoma mom, had a bad experience. In the spring of 2016, she posted on Facebook seeking treatment for her daughter Ashley, a meth-addicted 21-year-old who was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Treacy responded personally on Facebook Messenger: “Karie what’s going on??” He suggested Amethyst would be a good fit and that it would pay to fly Ashley, whose name has been changed, to Florida. “I just don’t want any surprises,” she replied. “We just don’t have a ton of money left after this 5 years of trying to help her. I am trusting in you and that’s hard because of past experience, I’m sure you can understand…I’m scared to death to send her so far away.” Treacy was reassuring: “I promise you she will be in a good place!!”

But things turned sour. Although Amethyst offers a “dual diagnosis” program—combined mental health and addiction treatment—staffers twice called the police on Ashley when she acted out, Dove said. Both times she was committed involuntarily to a local hospital. After the second episode—and after Ashley’s Blue Cross insurance was billed more than $100,000—Dove was told her daughter would have to find somewhere else to stay. Ashley had nobody in Florida. Following a stint at another rehab, she ended up homeless.

Citing privacy rules, Amethyst wouldn’t comment on Ashley’s case. “We provide individual treatment options to promote growth and healing,” the spokeswoman said. “Our licensed clinicians work with our case management team to ensure all clients are set up with the best possible aftercare.” Dove felt otherwise. For months, every time she saw a parent post on The Addict’s Mom seeking help for a kid, she would reach out, “trying to catch those moms that were new and didn’t know what the hell was going on.”

How is it, amid the most lethal overdose epidemic in American history, that such a medically advanced nation has such all-over-the-place drug treatment? One factor, experts say, is the stigma surrounding addiction. “These aren’t pregnant women or something where everyone’s going to go crazy if you mistreat them,” says Humphreys, the Obama adviser. Even friends and relatives, wary after years of relapses and manipulative behavior, don’t necessarily believe a loved one who says something is wrong with a rehab program, says Sherry Daley, an executive with the trade group California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals. “They’re going to say, ‘Wow, you screwed it up again.’”

There’s also the reality that requiring a higher standard of care—addiction medications and trained medical staffers—would drive many rehabs out of business. “That’s the mindset: that any treatment is better than no treatment at all,” said Bierman of the Maryland Addiction Recovery Center. “And for a lot of people, that’s just not true.”

Policymakers are catching up, albeit slowly. Major opioid legislation passed by Congress last fall requires the Department of Health and Human Services to develop best practices for sober homes. Patient brokers, at least in theory, can face federal fines of up to $200,000 and 10 years in prison. And while Arizona, California, Utah, and Tennessee passed anti-brokering laws in 2018, enforcement remains spotty. California has only 44 investigators to supervise roughly 2,000 licensed treatment facilities and little power over the many unlicensed facilities and sober homes.

At a December 2017 congressional hearing, Palm Beach County State Attorney Aronberg called for an outcome-based insurance reimbursement model to replace the current system of rewarding rehabs whether patients succeed or fail. Research shows it’s cheaper and more effective to step down addiction care gradually over a long period of time, he testified, than to put someone through “an unending series of intensive 7- to 14-day inpatient stays followed by intensive outpatient treatment for four to six weeks marked by overtesting and overbilling.”

A handful of insurers, including Optum and Medicaid programs in Virginia and Rhode Island, already bundle outpatient services such as addiction medications and case management for a fixed monthly fee, rather than paying for each trip to a residential rehab. And Shatterproof is working with 19 insurers to “identify, promote, and reward” treatment programs that meet basic principles of quality care, including access to FDA-approved addiction medications and coordinated care for physical and mental illness. The project includes a ratings system based on insurance claims that will show consumers how a given rehab measures up. “When they’re not being lured by plane tickets and palm trees, they can use this tool to make informed decisions,” says program director Samantha Arsenault. The new system is expected to launch in five states in the summer of 2020. In addition, the American Society of Addiction Medicine recently announced a new pilot certification system aimed at identifying rehabs that provide evidence-based care.

Finally, the rehab industry’s main trade group, the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, has revised its code of ethics to prohibit members from “buying and selling…patient leads” or “offering inducements and non-clinical amenities to prospective patients.” In January 2018, the association told 76 of its roughly 800 member organizations—including AAC, because of the website transparency issues—that they could no longer be members unless they changed their ways. Doing so cost the group more than $100,000 in dues. But “people are dying and nobody else is doing it,” says executive director Marvin Ventrell. “Our association can’t survive a holocaust of corruption.”

As of last November, Brianne had been off heroin for more than a year and home for six months. She was waitressing at Applebee’s and had been volunteering at the Humane Society. She had finally found a medication regimen that kept her depression and anxiety in check, gone to a dentist to fix a tooth the ex-boyfriend cracked, and seen a doctor to replace her long-expired birth control patch.

She didn’t really know how to explain this stretch of sobriety. Maybe it was her efforts to stay busy and distance herself from the Facebook recruiters. Maybe it was the support of her mom, who after all those years of sleepless nights had become a vocal advocate for better rehab treatment locally in Georgia. Because there’s no hard data to support the conventional wisdom that says you should send people far from home for drug treatment. “The idea that you go somewhere and have a semi-magical experience is problematic,” says Duckworth of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Addiction, he says, is a chronic disease that, like diabetes or heart disease, requires multiyear care tailored to the patient. Local facilities, in Duckworth’s view, are far more likely to provide such care and garner the support of family and friends: “Recovery happens in your own life, in your own home,” he says.

Even then, it’s a bumpy road. In early December, Brianne was picked up on an old arrest warrant. During her rehab-hopping period, she had failed to check in with her probation officer in connection with the DUI. Despite Jen’s protestations—that Brianne had been in treatment and far exceeded her community service hours—a judge sentenced her to 90 days.

Brianne turned 22 in jail, and when Jen visited her on Christmas Eve, they cried together—it would have been Brianne’s first Christmas home and drug-free since high school. Her cellmate is nice enough. And thanks to Jen, she has commissary credit for shampoo and conditioner and lotion. She watches a lot of TV and tries to tune out the schizophrenic woman in her unit who chatters incessantly. But when they talk on the phone, Brianne and her mom prefer to look to the future—to the breakfast they’ll enjoy when Jen picks her up in March, and to the coming fall, when Brianne will enroll at Georgia Highlands College if all goes according to plan.

If mother and daughter have learned anything, it’s that the future isn’t knowable. Last fall, Brianne passed a major milestone: her first paycheck as a sober woman. Not long ago, she would have spent that money on heroin. Instead, she went to the mall and bought herself a new purse.