From his cage in the far back of a courtroom in Newport Beach, California, Sam Woodward looked around. He appeared to stand on his tiptoes for a moment, peering through the bars at the gallery where his parents and a couple of family friends sat. He looked over at the judge and at his lawyer. He seemed confused and impatient. His hair, which had been combed neatly to the right in his yearbook photos, now fell in a loose mess around his ears. Usually clean-shaven, Sam sported a patchy, unkempt beard and a wiry mustache. A dirty undershirt poked through the collar of his orange jumpsuit.

Sam could see his mom, Michele, close to the front of the room. She was wearing a black blazer with black-and-white polka-dot pants. “I never thought I’d wear polka dots again,” Michele had told a friend in the hallway. “It seemed too cheerful.”

In between Sam and his family sat the counsel table, with a box for defense attorneys submitting paperwork. Pasted on the right side of the box was the David Mamet line: “Coffee is for closers only.”

Sam had been arrested on January 12, 2018, and charged with the murder of a former classmate, 19-year-old Blaze Bernstein. Police had found a knife stained with Blaze’s blood in Sam’s room, along with blood inside Sam’s car. Sam told police he had hung out with Blaze the night he disappeared.

Borrego Park was the last place where Sam Woodward said he saw Blaze Bernstein alive as he walked off in the moonlight.

Chloe Aftel

By this time, ProPublica had revealed that Sam was a member of a militant Nazi group calling itself the Atomwaffen Division. According to the group’s private chat logs, he was something of an expert on fascist thought and had been entrusted with vetting new members to make sure they were committed revolutionaries.

Sam was a timely villain. Atomwaffen made its debut in 2015, a year that saw white nationalist thinking lifted from the fringe to mainstream debate. The group had been connected with four other murders by 2017, and their chat logs were full of invective about Jews and gay people. Blaze had been both.

I had come to Orange County because there was something gut-wrenchingly intimate about this murder. Sam and Blaze had barely known each other in high school, just a few years before. And yet, here they were at a late-night rendezvous where one ended up allegedly stabbing the other 19 times in the neck, until the blood spattered onto the roof of the car.

The case appeared, and was reported in the national press, as just another data point in the resurgence of American extremism. And maybe it was—but there was not any indication as to how this hate had developed.

Sam had acted almost as if he wanted to get caught. He had given police the flimsiest of alibis. He had kept a knife with Blaze’s blood in his room and told investigators he’d last seen Blaze in Borrego Park, where his body was found.

And now, he had pleaded not guilty. At the hearing, he kept glancing at the door. There was no smile of recognition when he saw his parents, just a look of insecurity. His lawyer had told reporters that Sam was depressed, that he felt bad for his family and was reading the Bible in jail.

As I traced Sam’s life, I found a young man entranced by the validation that nationalist thought promised. He believed he was part of something important, something revolutionary. All he had needed for admission was hate and white skin. The Nazis were not hiding. They were waiting for guys like Sam with open arms.

I am a bisexual, Jewish man, just a few years older than Blaze was when he died. When I looked at his photos I saw myself, I saw family, and I saw friends. There was something cathartic to the tale of a neo-Nazi getting caught red-handed. But as I spoke with the people who knew Sam, reviewed court documents, and read thousands of pages of online messages, another story emerged. It was more complicated and sadder, in some ways, than the one I’d anticipated. Where I had seen a story about the endgame of American Nazism, there was instead a web of high school drama, alienation, and unspoken fears.

The rumors that Sam Woodward was interested in boys had been passed around at Orange County School of the Arts. A classmate, we’ll call him Jared, had told friends that Sam made a pass at him.

“It was hot gossip,” Lily Williams, Blaze’s best friend at OCSA, told me. “Like, ‘Isn’t it hilarious?’”

A public charter school nestled among some of the highest-income zip codes in California, OCSA is selective, with an audition required for admission and an artsy, progressive culture. Sam, a conservative from a devoutly Catholic family, didn’t fit in. He cultivated an aggressive, macho persona and seemed to relish upsetting classmates and teachers. In graphic-design class, he showed off a Confederate flag he’d drawn. For a music project, he chose Johnny Cash’s cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt,” an ode to self-destruction. He didn’t seem to have friends or be trying to make any. “Every high school has the kid who is just off,” Sean Corfield, who knew Sam then, told me. “If there was going to be a shooting, he’d be the guy.”

Blaze’s parents, Jeanne and Gideon, started a memorial fund after their son’s death.

Chloe Aftel

Sam didn’t talk to Jared about sexuality in school, but one day he sent him a message. “He was inquiring a lot in terms of my identity and wanted to know more,” Jared told me, “and that really surprised me because of how homophobic he was and because of all the opposed beliefs he had to my own.”

Jared had been openly gay since sixth grade. A chatterbox with a warm smile, he became the head of the school’s Gay-Straight Alliance. Nowadays he attends Northeastern University in Boston and works at a law firm.

“He would ask how I came out, how I knew I was gay, that sort of thing,” Jared recalls.

Sam continued to send Jared sexually charged messages. He was searching, it seemed to Jared, for a sense of belonging, the kind of identity he’d had so many questions about.

When Sam finally asked to meet up in person, Jared refused. He says Sam then propositioned him outright, “trying to meet up with me, hook up with me, and this was all very confusing because he wasn’t someone that was out.”

Jared cut off communication with Sam in 10th grade, uncomfortable at how things had escalated. They never texted again.

But Jared had been showing their messages to Blaze and another classmate without Sam’s knowledge. He didn’t mean to out Sam, he says, but he couldn’t help telling some friends. Sam transferred out of OCSA his junior year.

In the years after OCSA, Sam reinvented himself. He graduated from Corona del Mar High School and became an Eagle Scout, but he increasingly lived on the internet. He was interested in politics and created online accounts as, he would later tell a friend, “a confused conservative libertarian.” He hung out on an obscure photo-sharing app called iFunny, where his screen name was Saboteur. There, he found a teenage fascist who called himself Bil.

A baby-faced kid from the Midwest, Bil had played Little League but gave up sports as he got more introverted in high school. He read Nietzsche and adored the Italian fascist Julius Evola.

Starting in 2013, Bil began making a name for himself among iFunny’s far-right users by posting short essays about Evola, fascism, and “the existential and spiritual decline” of European societies. Most of his followers, Bil says, didn’t read the books he referenced, but they came to treat him as an intellectual of sorts who did the heavy lifting for them.

Through his high school years, Bil became the de facto leader of iFunny’s growing fascist community. He also started chat groups on other messaging apps, like Kik. They had names like “Youths Against Modernity” and consisted mostly of memes and complaints about women and how bad white men had it. “Bil was the head of the ‘movement,’” Patrick, one of Sam’s closest friends from iFunny, who asked that I use a pseudonym, told me over the message app Telegram. “If you could call it that.”

“I was kind of a false prophet,” Bil said with a chuckle when I reached him. He was mystified at first why I was calling—he didn’t remember anyone named Sam Woodward. I told him about the murder, and that Sam was Saboteur.

“That’s just…that’s fucking crazy,” Bil stammered. “I was never in—even when I was young and stupid I never would have—when did this happen?” January 2018, I said. He paused for what seemed a long time. “Wow. Are you serious?”

As Bil recalled it, Saboteur was relatively popular, albeit not particularly thoughtful, when they connected on iFunny. They didn’t talk much, but Bil didn’t find it hard to believe the platform would have been a big influence on Sam. “We were angsty teenagers and we needed an identity and that was the one, at the right time,” Bil says. “It’s really just whichever one makes you feel good, and then you attach yourself to that.”

There was something immediately satisfying for these boys, and they were almost all boys, about the simplicity of fascist thought and the misogynistic fantasies paired with it. It was an easy form of rebellion for guys too inhibited to act out openly. “I never was politically outspoken,” Bil explains. “No one I knew had any idea of my stupid Bil persona.”

“You know, some kids are goth, some kids are emo, some kids like punk music,” he adds. “I was kinda isolated growing up and didn’t have that many friends. So this was my sense of community.” Bil’s iFunny pages amassed thousands of regular readers and commenters, eagerly awaiting his diatribes on the fall of paganism and probing questions such as “Why is sodomy considered sex?”

RELATED: Inside the Radical, Uncomfortable Movement to Reform White Supremacists

For Bil, becoming more religious and heading off to a Christian college ultimately displaced fascism. Others weren’t so lucky. Two of his online friends have committed suicide, Bil told me. He believes many of the iFunny boys struggled with depression.

“Back in the day there was an intellectual component that made the app kinda worth it,” Sam told his Atomwaffen friends about iFunny later. “There were serious and academic people who could discuss theory and exchange ideas with debate and whatnot—leftists, capitalists, fascists, you name it—[but] then most of them left or became shitposters.”

As Saboteur, Sam became close with several other iFunny fascists. He inveighed about “faggots” and “kikes” and said he had a girlfriend who was a “generic trump supporter.” None of them had any reason to question this.

Like his online friends, Sam vibrated with sexual frustration. He talked about “conquest,” about “genetic imperialism” and wanting to “bone” a teacher of color at his school. He “liked dark skin girls,” Patrick recalls.

“We were aware of the hypocrisy,” Bil says, of complaining about identity politics while laser-focused on white maleness.

Patrick says he also heard about Sam claiming that he’d lost his virginity to a prostitute in Nevada—“because,” recalls Patrick, “he thought he’d never get laid.” This was consistent with what many of the guys complained about.

Some of the conversations reminded Bil of the incel movement and its notion that women are unfairly depriving men of sex, making them “involuntarily celibate.” Bil himself wrote that girls who said they were raped while drunk “rationalized whoring.” “We hated feminism,” Bil explains, “and female identity politics.”

“We were aware of the hypocrisy,” Bil says, of complaining about identity politics while laser-focused on white maleness. “But all identity politics is whining to a degree.”

The iFunny fascists whined about a lot of things. The “effeminacy” of “fags.” “Jewish success.” But in the end, they were desperate for two things: acceptance and sex. Acceptance came from within the community. Sex was more complicated.

Kruuz had a bricklayer’s physique and the paranoid charm of a revolutionary. He created and deleted online accounts religiously for fear he’d get exposed. One of his Atomwaffen friends called him “Kkkrazy Kkkruuz.”

He made his living working construction around the state of Texas—“You get fit while you make money,” he said once—but would sometimes go “off the grid” without warning or explanation. He didn’t get along with his family— “fuck parents,” he would say in the chats. “Parents are some fake ass ni—.” But every now and then, the loneliness would get to him.

“Who knows that feel when your whole family hates your dumbass,” he wrote one night. “I don’t want to feel this feel anymore of my family disowning me.” Zyklon, a member of the Texas cell, offered him a couch to sleep on. “You have family here,” Zyklon wrote. “‘Brother’ isn’t just a meme.”

“Its whatever,” Kruuz replied. “Imma just listen to some sad music.”

Friends remember Blaze (left to right: in first grade, at his 19th birthday dinner, and on vacation in 2017) as smart and generous, with a biting sense of humor.

Courtesy Bernstein Family (3)

It’s not entirely clear when Sam and Kruuz first met, but by early 2017 they were communicating in the Skype chats operated by the extremist group now called Vanguard America, which would gain notoriety when a man who had marched with it drove his car into a crowd in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing Heather Heyer. By then, Sam and Kruuz had become dissatisfied with Vanguard. They didn’t think it was radical enough.

Kruuz found Atomwaffen on Twitter, which the group’s leader, Brandon Russell, used to promote a book called Siege, written in the ’80s by a Nazi named James Mason. He encouraged readers to leave society behind and fight for its destruction. Mason exalted Charles Manson and encouraged isolated acts of violence—“lone-wolfing,” Atomwaffen called it—by small cells independent of one another and any national leadership. In Atomwaffen, the life-changing experience of reading the book was known as “Siegepilling.”

Kruuz tried to Siegepill Sam for months, and by April 2017 he had succeeded. But the two of them got on board with Atomwaffen just as all hell broke loose. One of Russell’s roommates, a longtime Atomwaffen member named Devon Arthurs, had converted to Islam. There was talk that Russell and Arthurs were planning to leave their home base of Tampa, Florida to visit Atomwaffen chapters across the country. Kruuz would have none of it. He told Arthurs, one member reported, “that if he came to TX he was gonna fuck him up.”

The dispute quickly became moot. On May 19, 2017, Arthurs shot his two other roommates, one of them also an Atomwaffen member, while Russell was out. He then, according to court documents, walked across the street to the Green Planet Smoke Shop and took several people hostage at gunpoint. He told police his roommates “were disrespecting” his new religion.

When investigators searched the house, they found several pounds of bomb-making materials. Some were stashed in the garage, in a plastic cooler with Russell’s name on it. There were also cardboard stencils and a can of red spray paint. A few recalled the hate group Westboro Baptist Church: “God Hates Fags.” Atomwaffen had added a swastika.

Blaze had that wavy brown hair. Sam saw it on his Tinder page. He had that Ashkenazi nose, too, the thin bridge that widened down into a schnoz. The one anti-Semites use when they draw us in cartoons. Among his online friends, Sam would have called him a “fucking absolute kike.”

Blaze was a talented writer, with a special knack for the supernatural. One of his short stories was published in the literary journal Bangalore Review when he was 17. It dealt with a boy being hunted across the African savanna by “Great Heron,” an ancient animal spirit.

“The boy ran as fast as his legs could carry him away from the spirit, away from the village, out of fear, shame,” he wrote. “The shetani [spirit] ran after the boy calling out vengeance. But before long, Great Heron was out of breath. Her endurance was no match for that of youth.” The boy is eventually strangled to death.

Blaze had never formally come out to his high school friends—he didn’t feel he needed to, Lily explains. “There was a lot he didn’t share,” she says. “I think he was comfortable with being a gay man but had the impression that to be out out he’d be burdened with some stereotypes. He was always worried if something was gay. I think there was some internalized homophobia to a certain degree.”

Lily Williams was Blaze’s best friend. “I always struggle” with understanding what the motive was for his killing, she says.

Chloe Aftel

Alex Tomlinson, another of Blaze’s OCSA friends, says it just “wasn’t a big deal for him. He was like, ‘Yeah, I’m gay,’ and that’s it. He didn’t feel the need to be a part of it. It wasn’t a part of him, but it was; it wasn’t his identity, yet it was.”

Sam and Blaze connected on Tinder in June 2017. The guy Blaze had been seeing was moving out of state, and Blaze was looking for someone to chat with, maybe to flirt a little.

Sam was good-looking, dashing in a certain light. A screenshot of his profile at the time shows him looking directly at the camera, blond hair whipped to the right in a side part. His face is clean-shaven, with a scowl under his bushy eyebrows. It was a pretty standard Tinder selfie, accompanied by a pretty substandard bio: “hey, hunting is pretty fun, politics are cool, game of thrones is alright i guess.”

Blaze recognized Sam from school. He “superliked” him, and within 30 minutes they matched. Blaze sent Alex a screenshot of Sam’s page.

“O M G WE ALL KNEW IT,” Blaze captioned the photo. “[Jared] was telling the truth for once holy shit.”

Blaze kept sending Alex screenshots. At first, they show, Sam maintained his familiar persona. “im on this app mainly because in terms of women, i’ve got jungle fever and fucked like 5 black chicks since i got on here a month ago,” Sam wrote. “in terms of men, i’m looking for an outdoorsy person to be a spotter and assist me in deer hunting.”

But they kept messaging, and after a while Blaze texted Alex, “Oh shit, he’s about to hit on me. He had me promise not to tell anyone…but I have texted everyone uh oh.”

“HAHAHAHAHAHA FUCK SAM WOODWARD,” Alex replied.

“I’m having to coax it out of him,” Blaze continued. “I had to stroke his ego to get him to tell me he thinks I’m hot please hold.”

Then there it was. “thing is,” Sam finally wrote back, “you’re not too shabby looking yourself Blaze.”

On October 27, after a week of intense political violence across the country, President Donald Trump stood on the tarmac of Andrews Air Force Base.

The previous Wednesday, a Kentucky man had shot three black shoppers in a Kroger store after failing to make it inside the African American church nearby. On Friday, a Florida Trump supporter had been arrested for allegedly sending 16 pipe bombs to Democrats and media figures. Then, just hours before Trump spoke that Saturday, a white nationalist entered a Pittsburgh synagogue and opened fire.

Trump was bundled in a heavy overcoat that afternoon, his comb-over bouncing in the wind. Two victims of the morning’s shooting still lay in Pittsburgh hospitals, fighting for their lives, as Trump speculated that, had the temple had armed guards, “maybe it could have been a very much different [sic] situation.”

“Look at all the violence all over the world,” he said. “I mean, the world has violence. The world is a violent world.”

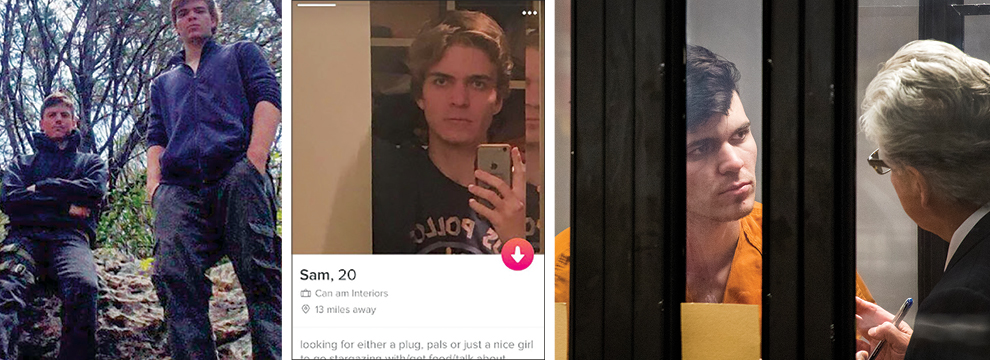

Left to right: Sam with his Atomwaffen friend Kruuz, in his Tinder profile, and in court after his arrest in January 2018

Tinder; Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times/Getty

To the Siegepilled, this state of random violence was a dream come true. “When indomitable wills despair,” Mason had written, “this is the exact point at which revolution appears within any society.” The more chaos, the more likely American society was to crumble under its own weight, making way for a fascist rebirth.

Of course, Mason cautions his acolytes, revolutionaries should never trust a politician. Still, he has written, “I find it a lot nicer just getting up in the morning knowing that there is a man in the White House who is not either a nothing or an outright sell-out.” Besides, he notes, “Make America Great Again could only mean ‘Make America White Again.’”

Mason’s work was rediscovered on the far-right site IronMarch, which published a PDF of Siege that it claims has been downloaded 16,000 times. His new fans in the battered tail end of the millennial generation had grown dissatisfied with the alt-right and found their heroes in the armed extremists of the 1970s and 1980s. They even tracked down Mason in Colorado, where he lived a quiet life as a retired Kmart security guard.

The Atomwaffenites helped Mason leverage his new online notoriety with a website to publicize his books (also available on Amazon, with five-star reviews) and a (now defunct) podcast. Mason told them to keep any proceeds “and put it right back into production.”

“The U.S. Right is made up of frustrated men,” Mason had written in Siege, “men who are afraid of this or that or the other and seek the company of others who are similarly frustrated and frightened, in order to be able to ease their angst and perhaps work out some of their fantasies.” In Atomwaffen’s internal chat logs, the young Nazis often griped about their boring lives.

“I’m a misanthrope with zero sense of humor,” wrote the group’s then leader, John Cameron Denton, under the alias Tormentor, “and cannot make friends due to being ridiculously and purposely disconnected even beyond an incel level with the exception of going to black metal concerts, getting drunk, and finding a hot piece of ass.”

In the chats, sex was a nonstop preoccupation, often with a distinct homoerotic overtone. There was a lot of talk about the male orgasm, and about members’ physiques—who was fit, who was tall, who was just a short “manlet.” Women were not allowed, and intense male-only bonding sessions were an integral part of membership.

The Atomwaffenites peppered Snow with questions—“WHY WOULD YOU BE IN THE PARK WITH A GAY JEW????”—but he didn’t have the answers.

Sexual violence was also a regular topic. Tormentor, who is in his mid-20s, opined that “teens are the best” when it comes to dating. A member known as Groz, part of Atomwaffen’s British affiliate, Sonnenkrieg Division, countered that 16 is “too old” because “body and mind [are] already polluted.”

In this, the Atomwaffenites were in line with their idol. Between 1988 and 1994, Mason was indicted in multiple jurisdictions on charges ranging from sexual contact with a minor to menacing with a deadly weapon, and he was convicted twice of possession of child pornography. (The sexual contact charge was eventually dropped.) In 1992, a judge banned Mason from ever returning to his home state of Ohio “without written authority from the Court.”

Sam came out to his parents as a Nazi in the spring of 2017. “He said his parents were cucks,” his friend Patrick told me, and he had to “explain why he was leaving.”

Sam had grown up in the coastal town of Newport Beach, half an hour from Blaze’s family. His neighborhood slowly had morphed from well-to-do to flat-out rich, its bungalows and ranch homes making way for McMansions. His parents attended Our Lady Queen of Angels every day, according to a priest at the church, and their names were inscribed on a monument to donors outside the building.

As Sam drifted deeper into the far right, he’d grown to resent aspects of his parents’ faith. Once he sent Patrick a topless Snapchat photo of himself looking miffed.

“tfw your christian father calls people who actively deny christ as their savior ‘Gods Chosen People,’” the caption read.

But Sam still loved his father and hoped that one day he’d join him in white nationalism. He believed he was “getting chipped away bit by bit.”

Sam spent that summer living with Kruuz in Texas. Sam and Kruuz roamed the state in Kruuz’s truck, hopping from motel to homeless shelter, always on the lookout for a construction job. “For months I was homeless and unable to find anything,” Sam told his comrades later. In July, they went to meet Mason in Colorado.

They were starstruck. Mason was tall—“a big motherfucker,” Sam recalled—and he spoke in a lilting baritone, somewhere between a Nazi Santa Claus and Harry Caray on heavy psychedelics. “Guy is full of stories,” Sam wrote in the chat. “Was like talking to a walking library.”

Mason lived in the shadow of dead Nazis. His apartment was filled with memorabilia—“relics,” he called them—from American Nazi Party founder George Lincoln Rockwell, Charles Manson, and the Third Reich. His book was itself an homage to an older Siege written in the 1970s by the fascist militant Joseph Tommasi. Despite a lifetime of service to the cause—he had joined the Nazi Party as a teen, 50 years before—Mason had never attained his forebears’ level of notoriety. He also had never bought a computer. All his missives were composed on a typewriter and sent through the mail.

I also asked him about a book called Art That Kills. In it, Mason describes getting “hung up” on a 15-year-old of whom he “had occasion to shoot a series of nude pictures.” He was in his mid-40s at the time. He describes another 15-year-old as “every old guy’s dream.” Minors that age, he told me, “may not be legal according to the statute. But according to God and Mother Nature they are perfectly legal.”One morning, Mason whipped up a steak breakfast for his guests. They peppered him with questions about Siege and the old days. When I spoke with Mason in January, he remembered Sam—“a fine, upstanding young man.” I asked what he would say if he could talk to him now. “I wish you had run this past me first; you wouldn’t be sitting there today,” he said. “But all good luck.”

I asked him about political violence, too. “I don’t advocate doing these things,” Mason said he would have told Sam, “but if you’re going to do it, for God’s sake make it worthwhile.” The synagogue shooting, he said, had not been “well directed”—the victims were too old. “You go out and you get the young thugs, the young toughs.”

By the fall of 2017, Sam had returned to his parents’ home in Newport Beach. He took a construction job that paid well and made him feel good. (“Kruz is right,” he wrote in the Atomwaffen chat. “You spend real time among real men, being a real man.”) He’d been boxing, he told the chat, with members of another far-right group. That fall, Kruuz moved to Southern California, where he took charge of the regional Atomwaffen chapter. Sam was his right-hand man.

Sam was still hoping to “drop out” of the system and told his comrades he was saving up to buy “farming materials,” so he took a job setting up bounce houses and Nerf battles for children’s parties. “Usually we cater to rich bourgeois pricks,” he wrote. Once he ran into a white woman with biracial children, which enraged him.

Sam was keeping a diary around this time—excerpts would end up being read in court—and some of the entries were about the “sodomites” he’d meet on Tinder and Grindr. How he would use the apps to “cuck” and “prank” them. They’d fall for him and he’d tell them how stupid they were. “That’s what they deserve for being fags.”

That’s also how Sam now described the experience with Jared. It was all an elaborate prank undertaken by his middle school self. “How fun it was back then,” he wrote, “to get that one faggot and then just cuck him all the time.”

Just after midnight on January 2, 2018, Sam was looking for Kruuz. He hadn’t heard from his friend in a while.

“has anyone talked to kruz?” he wrote. “I hope kruz is okkk.”

Another member reminded him that Kruuz often “fell off the map” and would “be fine” whenever he chose to come back. This seemed to comfort Sam, and he spent the next four hours chatting about video games and weed.

Later that day, he took to Tinder. He matched with another former OCSA classmate—I’ll call him Ted. “well, there’s a face I haven’t seen in awhile,” Sam messaged.

Ted did not know how to respond. In high school he’d heard the whispers about Sam. They’d been in class together but Sam rarely spoke. “He was choosing to be isolated,” Ted told me. “If you went to talk to him, it wasn’t like he wanted to talk back.”

Ted scrolled through Sam’s Tinder profile photos. He saw a Snapchat post of Sam complaining about his dad’s classical music and a photo of him at a gun range shooting a rifle. He took screenshots but never replied.

Blaze had been thriving at school after taking a semester off.

Chloe Aftel; Courtesy Bernstein Family

That evening in Lake Forest, Blaze Bernstein cooked a day-after-New Year’s feast for his family, repurposing some of what he’d served the night before.

“He made a dairy-free macaroni and cheese that he created the recipe for,” his mom, Jeanne, recalls. “He reused the butternut squash and made a really good soup and put it in the pasta too. It was delicious.”

Jeanne and her husband, Gideon, were happy to see their son thriving. After graduating, Blaze had gotten into the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Vagelos molecular sciences program, but he had taken a semester off to deal with some personal issues.

Blaze had returned to Penn in the fall of 2017 and had begun to settle in. He’d even been named managing editor of the school’s food magazine, Penn Appétit.

After they finished dinner that night, Jeanne left to take Blaze’s sister, 14-year-old Beaue, to a sleepover. Blaze and Sam were chatting online. Sam offered to come pick Blaze up.

It was around 11 p.m. when Sam turned into the Foothill Ranch neighborhood, heading toward the Santa Ana Mountains. He stopped at a two-story house in a palm-lined cul-de-sac.

Blaze came out wearing a striped T-shirt and sweatpants. He was not wearing his glasses and had left his wallet inside. The plan, it seemed, was not to go far. Together, they drove back down the hillside to the Foothill Ranch Towne Center. They sat there for a while, under the orange glow of the Hobby Lobby marquee. At 11:36 p.m., Blaze texted his friend Lily. “The gist of it was, ‘You won’t believe what’s happening right now,’” she recalls.

After waiting a while for Blaze to come back, Sam said, he went to his girlfriend’s house, though somehow he could not recall her last name or address. A couple of hours later, he claimed, he grew concerned and returned to the park to look for Blaze.Around midnight, Sam told police, the pair headed across the street to Borrego Park. On a good day, you could see for miles from here, all the way to the hills of Laguna Beach. Sam said this was the last place he saw Blaze. He said Blaze walked off through the entrance of the park, in the moonlight, to fetch another friend who would be a “surprise.”

The last messages on Blaze’s Snapchat, according to Lily, were from around this time. “They were all at 4 a.m. of Sam saying, ‘Blaze where are you? Are you okay? What happened?’” she says. “I think it was him putting breadcrumbs of a false trail.”

That first night, Blaze’s family didn’t think he was missing. They didn’t get worried until he failed to show for a dental appointment the next day. Blaze was always on time.

By 10 p.m. on January 3, the Bernsteins were growing increasingly concerned. Beaue logged into Blaze’s Snapchat to see if she could find any clues. Then she texted Lily.

“are there weird unfamiliar usernames,” Lily asked. “don’t open any photos.”

Beaue scanned through Blaze’s account looking at everyone he’d messaged with. One name stood out: “who is sam woodward”

On Thursday, January 4, Dylan Jantzen, a sheriff’s investigator on the case, was in Borrego Park, trying to get the lay of the land, when he noticed Sam Woodward walking by. They talked. Sam told Jantzen about the meeting with Blaze. He said that at one point Blaze had kissed him, that he got mad and Blaze apologized.

Sam told the officer that he found homosexuality “disgusting,” but that at the same time, “the idea of being with another man was something of interest to him.” He walked Jantzen along the route he said he’d taken as he looked for Blaze in the early morning hours. Across the park were the trees where the body still lay.

After Sam picked up Blaze, they sat in the Hobby Lobby parking lot for a bit. Blaze texted his friend Lily at 11:36 p.m. “It was something along the lines of ‘You’ll never believe what’s going on,'” she recalls.

Chloe Aftel

That Sunday, Sam took communion at Our Lady Queen of Angels. Two days later, a cold front moved in, bringing much-needed rain to Southern California. It washed away some of the dirt covering Blaze’s body. He had been stabbed 19 times in the neck, 14 times on the left, five on the right. His face was also injured, and he’d been stabbed on his left knee.

In the park, prosecutors said, Sam had found a little clearing and dug a shallow grave, pulling up clumps of the cold, chalky dirt. When police interviewed Sam, they noticed his nail beds were caked with it. He claimed he’d fallen in mud. His arms were scratched—Sam told the cops this was from a fight club he was in.

When Sam got home to Newport Beach, he did not throw the folding knife away. He kept it in his room, letting Blaze’s blood coagulate into a rust-colored stain on the blade, which was etched with his father’s name.

Lily had a huge crush on Blaze when they first met in a creative writing class her freshman year. “Obviously,” she says with a grin, “that didn’t work out.”

As Lily explains it, they had a near-identical sense of humor and similar tastes in art and music. With a scrunched-up nose and an ever-present smile, she once dressed up as the PBS Kids character Caillou after shaving her head. She and Blaze were supposed to hang out on January 2, but she had canceled.

Even after all these months, the killing doesn’t make sense to Lily. “I always struggle with placing what Sam’s motive was,” she told me. “I know he was outed in the OCSA community. But I don’t know if Sam is actually gay or not, or if that earlier thing at OCSA was him trying to find a target.”

In high school, Blaze wrote Lily a letter that she has kept as a photo. Composed in Blaze’s neat cursive, it reads, “Everyday you walk around, strutting the epitome of beauty in its simplest and finest form: you. You are the epitome of all things good and wonderful on this earth.”

“Just kidding. I hope you die you stupid bitch. XOXO.”

Blaze Bernstein’s body was found in Borrego Park.

Chloe Aftel

That’s the way Lily and Alex like to remember Blaze. He was not one for sentiment, though he could be extremely caring and supportive to his closest friends. Just as often, he was snarky, sarcastic, even rude.

“He stuck to the people he cared about and everyone else he was kind of a bitch to, and it was really funny and I kind of loved that about him,” Alex says. “He was very real and straightforward.”

After Blaze died, his family created a memorial fund. They went on television to talk about his life and started the hashtag #BlazeItForward. When I visited their home three months after Blaze’s death, his car was still parked outside on the curb. Inside, the house was filled with photos of him, collages made by well-wishers, and cards sent from around the country. The family’s dog scrambled around our feet.

Jeanne and I sat in the living room with the family’s publicist. A lawyer by training, she was guarded in her answers. Just like Blaze’s friends, Jeanne acknowledged that she had learned some things about her son by osmosis. Blaze had never really discussed his sexuality with his parents, but by the time he went to college, she said, “I knew.” I asked what the family had talked about with Sam when they contacted him after Beaue found him on Snapchat, before Blaze’s body was discovered.

“I don’t think that’s going to be spoken about,” she demurred. “I want to make sure this young man gets a fair trial.”

I tried for months to interview Sam’s lawyer, his family, his parish priest, or anyone else who knew him in Newport Beach. Virtually no one wanted to talk. Only the online chats, where Sam spent so much of his time, offer a glimpse inside his mind—and even that picture is blurry. What you put on the internet, we’re so often told, is permanent, but in fact our digital lives can be evanescent as fog. Jared no longer has access to the Facebook and Snapchat accounts where he says Sam messaged him. Sam’s iFunny page was deleted, as were those of many of his friends, including Bil. The forums on IronMarch, where Atomwaffen recruited members, were also lost in 2017, when the site’s creator deleted it all.

The Atomwaffen chats remain, however, and it was there that Sam posted an unusually emotional message on January 5, three days after his encounter with Blaze: “i just wanted to let you all know i love you so much.”

His comrades found out about the murder the same way everyone else did—from the news. They were mystified. Some thought Sam was a “moron” for killing a seemingly random victim. Some were hopeful it would inspire “copycat crimes.” “Just like Al Qaeda,” one wrote. “Only better.”

A user called Snow, who knew Sam personally, had spoken to Kruuz and reported that he, too, had not seen it coming. “No one knew he was going to do this,” Snow said. “Not even Kruuz, and they’re best friends.”

The Atomwaffenites peppered Snow with questions—“WHY WOULD YOU BE IN THE PARK WITH A GAY JEW????”—but he didn’t have the answers.

“People can hide things and cover up really well,” he wrote. “Some people just snap.”