Last Tuesday evening in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Forrest Liu, 27, spotted a blue sedan with four passengers idling at the curb outside a barbecue restaurant, where a woman in a red apron could be seen stacking paper takeout containers on the counter, preparing to go home for the night. Liu, with round glasses, a black beanie, and Nike shoes, recently started leading a patrol of the area, sort of like a neighborhood watch.

He lifted a walkie-talkie to his face and called for backup. “Can you come to Stockton and Jackson?” he asked, sharing his location with another volunteer.

He wasn’t necessarily nervous about the car, which could have been there for any number of reasons, but he wanted to be vigilant just in case. Attacks against Asian Americans had been rising in the Bay Area—and around the country—for months, with at least three assaults over the prior week in the city, including of a 75-year-old woman and an 83-year-old man. An idling car with multiple passengers could in theory be an easy escape vehicle if someone wanted to jump out and rob a shopkeeper. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong, but if anything is wrong, the more people they see observing, the less likely something is gonna happen,” Liu told another patrol member, continuing to watch the car. About five minutes later, the driver pulled away. “I think they got spooked by us,” Liu said to a woman with dyed purple hair, another volunteer who’d come to join him.

Chinatown Safety Patrol volunteers meet at 5:30 p.m. at Portsmouth Square in San Francisco’s Chinatown before going on a patrol. Messages painted on the ground remain from an AAPI rally the previous weekend.

Mike Kai Chen

About a month and a half ago, Liu helped create the Chinatown Safety Patrol after hearing about Vicha Ratanapakdee, an 84-year-old Thai man who died in January after a 19-year-old shoved him to the ground on his morning walk. In San Francisco and nearby Oakland, at least a few other volunteer patrols have sprung up over the past year in response to assaults against Asian Americans—violence that has always been a problem but seemed to escalate with the pandemic, as Donald Trump spewed racist rhetoric from the White House, as the streets became emptier, and as isolation and unemployment exacerbated mental health and substance abuse issues that can lead to crime. Other community groups have launched “chaperone” services, walking elderly neighbors to their errands, or have started offering counseling to survivors of attacks. This grassroots outreach is also a response to, and shaped by, ongoing conversations about what public safety should look like while cities continue to grapple with demands to address racism and police brutality. “I’m here,” Liu said to the other volunteers, “because you care about your community, you care about your family, you see what’s happening, and you want it to stop.”

Liu leads a group of volunteers through San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Mike Kai Chen

When Liu first set out on a patrol several weeks ago, it was just him and a friend or two, walking the streets and asking shopkeepers what they needed. But after a white gunman killed six Asian women in Atlanta massage parlors in mid-March, many more people came out to join him; 20-plus volunteers gathered on this Tuesday night, wearing face masks and bundled in coats. Among the group was Jerry Yim, 51, who himself was the victim of violence recently, sucker-punched in the face while he commuted home to Chinatown from work. Initially, he said, the police didn’t want to investigate until he found security footage of the incident himself. “That’s why people don’t report these things,” he said, noting the effort involved. (The San Francisco Police Department did not respond to a request for comment.) Another volunteer, Keith Hong, 32, started patrolling days earlier, thinking of his family back in Brooklyn. “If I was home, I’d be walking my grandmother everywhere,” he told me. “To know that I can help somebody else’s grandma, that means something to me.”

These patrol volunteers came from diverse backgrounds, students and engineers and techies and activists, many without prior self-defense training. A majority of them were of Asian descent. Liu, a contractor who moved to the city recently from Berkeley, told the full group their role would be to try to prevent crime, largely by being observant and greeting everyone they passed. “Saying hi is acknowledging that you see someone,” he told them, before breaking them into smaller groups to start walking for an hour or two. “One of the biggest deterrents we have is by being there and by them knowing we’re here.” The goal, if an incident does occur, is to stop, watch, and record what’s happening with a phone, to be a reliable witness for law enforcement later. But ideally, volunteers can deescalate tensions and prevent things from boiling over in the first place, sometimes by simply asking people who look upset whether they’re okay or if they need help.

As Liu walked up and down Stockton Street, a busy thoroughfare with restaurants, jewelers, and cash-heavy businesses, he noticed a man with a yellow hat waving a crutch and yelling in an intersection. The man crossed the street and then lingered by a grocery store, with potatoes and oranges and greens for sale outside. Liu watched for a minute. A day earlier, a store owner nearby found a guy trying to shoplift and deescalated the situation by buying the person food from a neighboring shop. “He might just be hungry,” Liu said now.

Volunteers patrol the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Mike Kai Chen

Other patrols use similar tactics, focusing, when possible, on support and community-building. Leanna Louie, an Army veteran who immigrated from China at age seven and now leads different patrols in San Francisco’s Chinatown with the United Peace Collaborative, says that when she recently saw a man peering into parked cars, she asked how he was doing and helped buy him some pork buns after hearing he needed food. Her volunteers also try to improve the atmosphere in the neighborhood by removing graffiti and promoting events organized by merchants. “But our main thing is, we’re out there as extra eyes and ears to help citizens,” she says. “A lot of times when crime happens, they’re startled, they don’t know what to do.”

One of the first decisions after a crime happens is whether to call the police. In mid-March, San Francisco Mayor London Breed announced that more cops would be deployed to neighborhoods with many Asian residents and businesses because of the recent attacks, a change that’s been welcomed by some shopkeepers and residents in the city’s Chinatown. Liu says police with Mandarin and Cantonese language skills who are familiar with the community can be good resources. He and Louie both reach out to law enforcement if they observe crime during their patrols, and so far, Louie hasn’t seen officers act out of line. But, she adds, if cops were to abuse their power locally, she’d record that too, and report it to city officials: “We don’t care if you’re police or a criminal; we record what’s going on in the streets.”

Other activists worry about beefing up the police presence because law enforcement officers, they point out, have a history of inflicting violence on people of color, including Asian Americans. Just at the end of last year, Angelo Quinto, a 30-year-old Filipino Navy veteran, died after police pinned him down by his neck in Antioch, east of San Francisco. And vulnerable or marginalized groups like sex workers, unhoused people, people struggling with mental illness, or formerly incarcerated people are particularly at risk of being harmed by cops; my colleague Madison Pauly recently explored, for instance, how massage parlor workers in Atlanta and other cities do not see increased police presence as an answer to the threats they face. “The police are ineffective at keeping communities of color safe,” says Kim Tran, an Oakland-based author who studies Asian American solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. “If we want more public safety, we need to have comprehensive programming, beyond just policing,” adds Alvina Wong, an organizer with the Asian Pacific Environmental Network in Oakland who wants to see more support for housing and mental health resources.

Beefing up policing could also pose a threat to Black neighbors, and worsen racial tensions that have flared after media reported that some suspects accused of assaulting Asian elders in Oakland and San Francisco are Black, including the teen who fatally pushed the Thai man. In San Francisco, organizations like the Chinese Progressive Association are trying to bridge the gap, facilitating dialogue sessions for Asian and Black residents to share their experiences. (The association also works with other grassroots groups to provide wraparound services, language help, and counseling to survivors of crime.) “Oftentimes communities of color are living on top of each other—you have Black community members who have been displaced in their own city living alongside a growing Asian American population,” says Shaw San Liu, executive director of the association. “Many people can’t access what they need for basic, decent lives—from jobs to housing to health care. It’s about holding space and facilitating conversations between people who otherwise would have no way to communicate, to break through some of the ways we’ve been taught to dehumanize each other.”

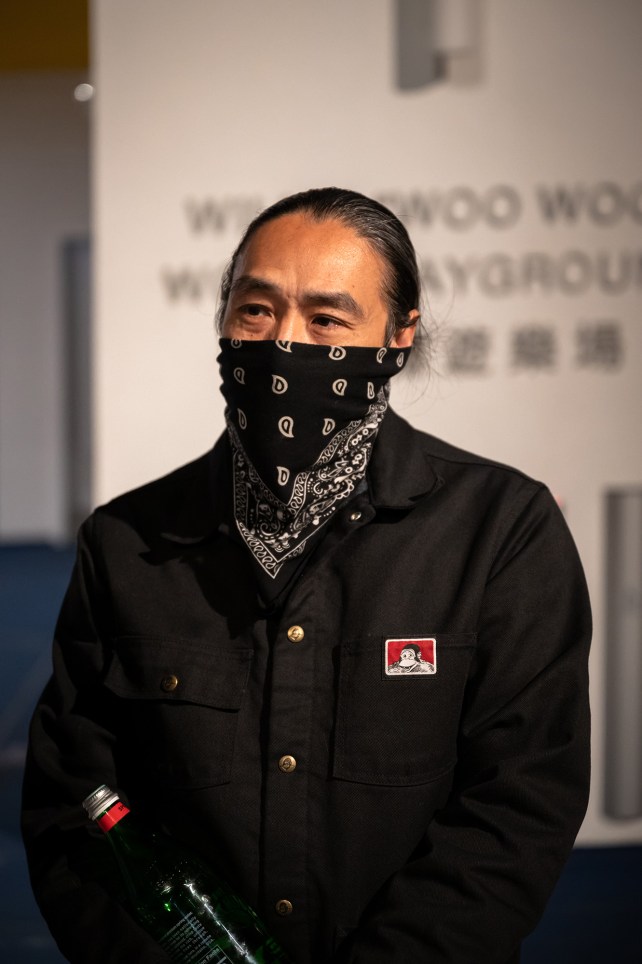

Max Leung, one of the original founders of patrol groups around Chinatown.

Mike Kai Chen

It’s important, though, to hold space for people not just in Chinatown—where the safety patrols and much of the media are focusing—but also across other pockets of the city where certain crimes are rising too, including in other majority-Black and Asian areas. In the Richmond District, Pam Tau Lee, a longtime organizer who is 73, says she barely left her home for months after a white man shoved her at a Starbucks during the pandemic. Her daughter-in-law and son bought her pepper spray and an alarm button, but she was too scared to venture out until a couple of weeks ago, when she sent an email to her neighborhood group, Richmond District Rising, asking if someone would accompany her. Within minutes, multiple people responded. “It was great to be able to be outside and just walking and laughing and talking,” she says. “For me, it’s important to not come at this as a victim, but to come at this with an open-heart faith in our community, to put your vulnerability out there and just kind of step up.”

The volunteer safety patrols are a clear sign that people do want to step up and, in particular, help their elders who have faced lifetimes of racism. “Violence against Asian Americans has been going on for years and years, even back in the railroad days, and it was never a big deal—people didn’t care about it,” says Louie, who recalls being bullied as a child in school in San Francisco. “It seems like we’ve been invisible all these years. And finally now, we’re starting to show up.”

Chinatown Safety Patrol volunteer Kewesi Simon.

Mike Kai Chen

But the volunteer groups are also new, and they often have to figure things out on the fly, without many resources. Forrest Liu, for his part, tells me the Chinatown Safety Patrol is not doing any fundraising and relies on people donating their time and other resources. Last Tuesday night after walking around Stockton Street, he gathered the other patrollers near a local playground for a training session with Kewesi Simon, a former bouncer and martial arts instructor in Oakland who now works as a personal trainer and teaches people to defend themselves. Simon spoke with them about scanning their environment while they walk, and about deescalating situations by talking with people from a distance. He urged them not to put their hands on anyone without enough training, and encouraged them to follow protocols their organizer set for the group.

Simon, who is Black, said he’d be happy to continue volunteering with the patrols in the coming weeks. “Any racism toward one of us is racism toward all of us,” he said of the escalating violence.

After the training, most of the volunteers headed home and Liu stayed back to strategize. He hadn’t set formal protocols yet because the group had been so small until recently. On a park bench, he sat with Simon and another organizer, writing down guidelines for how to respond if volunteers see a weapon, and how to go about alerting police. Liu told Simon he’d need to order some body-cams, plus more walkie-talkies, since he only had two. It would take a lot of work to build up an operation that he never imagined would grow so quickly, and to make sure everyone, including volunteers, stayed safe in the process.

Simon teaches a self-defense class after a patrol session.

Mike Kai Chen

Simon, who leads KES Fitness in Oakland, demonstrates a body camera he wore during the day’s patrol.

Mike Kai Chen

“This is another example of communities trying to fill a void left by bigger systems and being underfunded in doing so,” says Tran, the Oakland-based author. She thinks the patrols and chaperone services are a good idea and wonders what they would look like if they weren’t only run by volunteers, but had more investment from the city, with more substantial resources behind them. “Because who wouldn’t want someone to walk with them to the store if they were afraid? I think that’s really beautiful. Even if the reason why we have to have this is unfortunate.”

Some more resources may soon be on the way. Last Wednesday, Mayor Breed announced that the city of San Francisco would launch a new community safety effort to protect members of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. By this summer, the city hopes to send culturally competent outreach workers as part of safety teams into Chinatown, the Richmond, and other neighborhoods as an extension of an existing violence intervention program. The city will also expand a senior escort program to accompany more seniors on errands.

In the meantime, it seems that neighbors will continue to lend a hand. Standing outside the park at the end of Tuesday night, Liu said he isn’t sure how long he’ll be walking in Chinatown, looking out for potential violence. “I don’t want to patrol forever. Nobody here wants to,” he says. “We’re just gonna do it until it stops.”

Empty streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown after most businesses close by 7 p.m.

Mike Kai Chen