Early on a Saturday morning in June 2015, a passerby notices a silver BMW stopped at an off-ramp in Oakland, California. The car’s turn signal is on, and the motor is running, but it doesn’t move as the traffic light cycles. Through the tinted windows, the driver appears passed out in the front seat. So the bystander calls 911 to report a medical emergency.

Soon, armed police officers swarm the scene. If they are concerned the driver might need a doctor, another fear comes first: There’s a gun in the front seat. As the clock ticks, this fact prevents them from getting the man—who is Black—to an ambulance. Instead, they run their sirens in useless attempts to rouse him and put spike strips under his tires. “This is the Oakland Police Department,” a PA system blasts. “Get your hands up.” An hour passes. The driver remains unresponsive.

That morning, the man in the car is Demouria Hogg, a 30-year-old father of three. While farmers market vendors arrange their stalls with lettuce and strawberries down the block, officers shoot out Hogg’s taillight with bean bag rounds and use a metal hook to smash his passenger-side window. This last attempt may have awoken Hogg; officers’ recollections are murky. But what happens next is captured on bodycam footage: A phalanx of cops rushes the car, shouting commands at Hogg and breaking the driver’s side glass. A rookie officer will later claim that as the window shatters, she sees Hogg move his hand toward the passenger seat, where she knows there is a gun. She puts a bullet in his chest, killing him.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

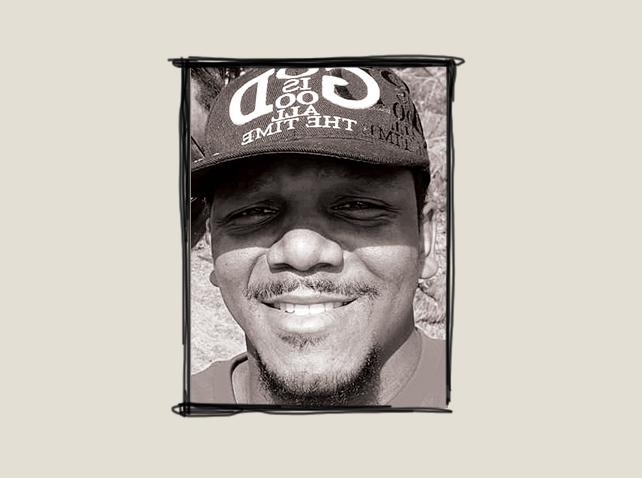

On another spring morning, six years later and less than 2 miles away, a silver hatchback is crashed into a parked truck on Oakland’s East 25th Street. The hilly dead end, lined with apartment buildings, sits near the border between Oakland’s tech-enriched, gentrified neighborhoods and its lower-income, Blacker flatlands. This time, the unconscious man is Lavel Jones, a 32-year-old father of four, whose stereo blasts old-school R&B for almost an hour before a neighbor notices the car and Jones passed out in the front seat. She calls 911 out of concern for his health. Cop cars and an armored BearCat descend on the block, along with an ambulance that waits down the road. The police, spotting a gun in Jones’ lap, run their sirens and bark orders.

What happens next—a series of events involving a filming bystander, a burgeoning anti-police organization, court-ordered police reform, and Jones’ own mother—has everything to do with the questions many started asking after the murder of George Floyd. Are police the best way to keep us safe? Can they be reformed? Are they necessary—or even equipped—to respond to the mental and behavioral health issues that underpin many emergencies? And if not police, who?

Jones’ experience might just point toward some answers.

On the morning of May 11, 2021, Carina Lieu watched from the window of her apartment on East 25th Street with growing anxiety as cops raised their guns at the man in the hatchback. Lieu, a 36-year-old city government employee born and raised in Oakland, was particularly horrified by the police response because she was one of the people who had called them. That morning, she’d noticed Jones’ car and, on her way to drop her 1-year-old off at the babysitter’s, decided to check on him, wondering if he needed a doctor.

Lieu had just spent months immersed in local debates about policing for her job, which involved setting up trainings and guest lectures for teenagers participating in the city’s Reimagining Public Safety Task Force. “We can create safer communities if we are willing to have an openness to imagine and the financial investment to match,” the committee, formed after police murdered Floyd in Minneapolis, wrote in one of its guiding principles. “Let us invest as aggressively in proven, community-based alternatives as we have in punitive and violent policing and incarceration.” The task force ultimately issued 48 recommendations to increase police accountability and create alternative responses to harm in Oakland, such as hiring residents to be “violence interrupters” and investing in a counselors-not-cops emergency response program.

Those alternatives had not yet become reality when Jones crashed his car on Lieu’s block. 911, she felt, was her only option. But by the time she returned home from the babysitter’s, police had taken over the street. “I didn’t want this man to die because I called the police,” Lieu says. “I also didn’t want him to die if I didn’t call the police. I just thought he needed medical attention.”

As she watched with growing dread while police pointed their guns, she remembered the Anti Police-Terror Project, an activist group that had recently launched a community-based hotline called Mental Health First as an alternative to 911 in Oakland. The group might know what to do, Lieu thought. So she texted some colleagues, asking if they could get in touch with the organizers.

Lieu’s plea made it to Cat Brooks, who co-founded APTP in 2012. Brooks, a progressive powerbroker and former Oakland mayoral candidate, had been on the frontlines of local anti–police brutality work since 2009, when a transit cop shot Oscar Grant in the back on an Oakland train station platform. The goal of APTP was to get beyond protesting, to actually prevent police violence against people of color—by training community members to interrupt police abuses when they happened and finding ways to reduce contact between cops and the community.

When Demouria Hogg was shot in 2015, his death hit Brooks particularly close to home: Her daughter and his were best friends. The killing marked the start of what she now calls “bloody 2015”: seven months, five Black men killed by the Oakland Police Department. “We were always in the streets,” she remembers of that year. “We were always at OPD headquarters.” As the death toll mounted, Brooks and her group implemented their two-part playbook, which involved on one hand taking cops on, and on the other supporting families. They documented and investigated officers’ actions, organized vigils, and fundraised for victims’ families or connected them with lawyers. Informed by what they learned that year, the group launched a campaign to reduce OPD’s budget, years before “defund the police” became a national rallying cry and a locus of political controversy.

APTP—originally a “rag tag fringe group of radicals” in Brooks’ words—had never intended for its own organization to replace the police. But as its reputation grew, people started reaching out to its volunteers instead of 911 for help with emergencies. The first call, Brooks says, involved domestic violence; the second, a mental health crisis. “People didn’t want to call the police, so they called us,” Brooks says. “At some point, we looked at each other and went, ‘Well, we better come up with an actual model.’ Because if we’re going to tell people not to call the police, we goddamn well better have an alternative.”

The solution they devised is MH First. The hotline dispatches volunteer medics, mental health specialists, and security to respond in person to people dealing with psychiatric emergencies, substance use, and interpersonal violence. For now, MH First is operating just on the weekends. But when Lieu’s texts for help reached APTP organizers that Tuesday morning, their volunteers sprang into action.

“Oh my god, this is like Demouria all over again,” Brooks remembers thinking.

Rebecca Ruiz, a volunteer with the hotline, was on her way to check on a sexual assault survivor she’d assisted the previous day when she heard from Lieu. Ruiz texted Lieu instructions as she rerouted to East 25th Street: Film the cops. Let them know they were being watched. Demand they allow the man medical treatment. “Be calm when you speak to them,” Ruiz advised. “We don’t want them escalated further.”

In Lieu’s videos, the police run sirens and make announcements over and over, trying to be heard over Jones’ music. According to police records, they called in a helicopter; pictures from the day show a police dog on the scene. Lieu says she also saw officers bump into the crashed vehicle with their own SUV, knock on its window with a metal pole, and train their guns on the car.

Ruiz and Brooks met at the end of the street, where police had stretched yellow tape across the intersection. Neither could see up the hill to where Jones had crashed. Brooks demanded the police allow as much time and space as needed to get the man out of the car. “You all are going to shoot him,” she remembers saying.

Oakland police chief LeRonne Armstrong says police at the scene that day were already doing what Brooks was demanding—taking their time and staying at a distance while they tried to communicate with the man in the car. But her accusation wasn’t unfounded. In addition to Hogg, cops around the San Francisco Bay Area have killed at least three people who were unconscious or sleeping with a weapon over the last couple of decades. John Burris, a civil rights lawyer whose firm represented all four victims’ families, says each shooting came down to “poor tactics, poor policing, failure to deescalate.” “What I’ve seen in every one of these cases, the person was semi-unconscious, kind of coming out of the sleep that they’re in, having a sort of bewildered look on their face,” Burris says. “And during that process, they get shot.”

As Brooks negotiated, Jones’ mother was racing to get to East 25th Street. Alissa Webb-Breaux had been driving to her Pittsburg home, about 45 minutes away, when she learned that Jones had crashed his car, and the police were surrounding him.

Jones was Webb-Breaux’s oldest son. She had raised him on that block. When they moved away to the hills years ago, she tells me, she was “trying to keep him out of Oakland”—and situations like the one he now found himself in. But Jones had kept his childhood friends, and according to Webb-Breaux, one had recognized him in the crashed car and called his family. Jones’ mother, sisters, and mother-in-law all rushed to the scene, bringing along his children. “As a mother, I just turned around and got there the fastest way I could,” Webb-Breaux says. “They were telling me he was asleep, and they couldn’t wake him up. I said, ‘I can wake him.’”

When Webb-Breaux arrived, Brooks was on the phone with Oakland’s city council president, Nikki Fortunato Bas, trying to enlist her help in demanding police follow the principles of deescalation. Bas, in an interview with me, says the events Brooks described on the call reminded her immediately of Hogg, whose vigil she’d attended six years earlier. She agreed to relay Brooks’ requests for time and space to Armstrong. But before they hung up, Brooks learned that Jones’ mother had come to the scene. If Jones were to be saved, Brooks thought, he needed someone he trusted to approach him. So Brooks added a final request: To let Webb-Breaux go to Jones, wake him, and get him to an ambulance.

The family was in a state of panic. Webb-Breaux told Brooks that her son struggled with drug use and mental health issues. She suspected that he had simply gone too long without sleep. But she also feared he might be suicidal. To Brooks, Webb-Breaux had just listed off all the reasons why cops might justify shooting Jones. She asked if Webb-Breaux would be willing to go through the police line to speak to her son, and Webb-Breaux instantly agreed. “You’re our best bet,” Brooks remembers telling her. “Even if he’s not sharing our reality with us, in whatever reality it is, you’re still Mama. You’re always gonna be Mama.”

Bas passed the message to Armstrong, who in turn called the officer in charge of the scene to advise him that Jones’ mother was there and willing to participate. By then, with Brooks’ help, Webb-Breaux was already talking to officers. Within minutes, she’d been escorted up the hill into the swarm of cops surrounding her son. “I just couldn’t believe there were so many police with just one person,” she tells me. Three police vehicles blocked in Jones’ car. Five officers were positioned behind one cruiser. Another kept a gun trained on the hatchback from the turret of the BearCat.

All those police, Webb-Breaux knew, were going home at the end of the day. Her son might not.

An officer instructed her to climb up on the side of the BearCat, where she could get a view of Jones. When she saw her son, she says, words rose to her lips: a verse from a song by Oakland rap legend Too $hort. “Don’t ever give up, I know it ain’t workin’,” she recited. “It’s been a long time, you never stop tryin’.”

Lieu’s video captured more of her words: “I love you,” Webb-Breaux said. “Your sister’s down there, and all your friends.” She told him to put his hands where the officers could see them.

“I was just so scared,” Webb-Breaux remembers. She worried she would talk Jones out of his stupor, only for him to be shot.

By then, Jones was emerging from sleep. Slowly, as his mother kept talking, he began to respond to her instructions. First, he stuck his hand out the window. Then he opened his door. At last, he rose, and the gun clattered off his lap to the ground. In that moment, Webb-Breaux says, she heard multiple officers prepare their weapons. Click-click-click-click. “Any move he would have made,” she says, “it would have been over.”

But Jones didn’t make a move. Police didn’t fire. He backed up from the car a step at a time, hands raised, toward the officers. Then he paused. “Come on, you can do it,” Lieu shouted from her window, still filming from her phone. “Just take your time—it’s OK.” Two more steps. Then police rushed forward to cuff him.

Down at the intersection, Brooks watched Jones’ son push through the police line and run to hug his father.

In an Oakland law library in 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale dashed off the 10-point platform for a new organization to resist police violence: the Black Panther Party. As Donna Murch writes in Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, Newton’s and Seale’s families—as well as those of their soon-to-be recruits—had fled the Jim Crow South for greater opportunity in Oakland, only for the city’s wartime industrial boom to collapse, sending their communities into poverty. The virtually all-white Oakland Police Department responded to the growing Black population and its economic struggles with arbitrary arrests, harassment of interracial couples, and sweeps of Black neighborhoods.

Newton and Seale’s platform 55 years ago demanded “an immediate end to police brutality and the murder of black people.” Their method was community intervention. They started neighborhood patrols that monitored cops on the street, openly carrying firearms both to deter brutality and attract new recruits. “Usually, the police wouldn’t brutalize anyone if we were on hand,” Newton told one interviewer from a jail cell. “The police are there in our community not to promote our welfare or for our security or our safety, but they’re there to contain us, to brutalize us, to murder us.”

Gun control laws put an end to the Black Panthers’ open-carry patrols; a violent police backlash and a lethal FBI sabotage campaign all but ended the party in the 1980s. Yet their political analysis of policing and public safety lives on—in cop-watching groups, among police abolitionists, and in Brooks’ work with the Anti Police-Terror Project. “The birth of the Black Panther Party—that’s whose shoulders we stand on,” Brooks tells me.

With every “officer-involved” shooting, every brutalized Black teenager, every unjustified arrest that ends in tragedy, the imperative to find another way becomes more urgent. Today, the abolitionist maxim “We keep us safe”—embedded in the Panthers’, and now Brooks’, work—is being realized by a growing number of community-driven alternatives to policing. In the San Francisco Bay Area, volunteers of Asian descent have organized community patrols to prevent hate crimes in San Francisco’s Chinatown, while young Black abolitionists agitated successfully for Oakland Public Schools to replace school cops with counselors. Cities from Denver to New York are implementing programs modeled on a long-running Oregon program called CAHOOTS, which diverts low-level 911 calls away from police, instead dispatching counselors and medics. APTP now holds bimonthly calls with community groups and government officials pursuing similar initiatives across the country.

Oakland is starting one of these programs, too. Called MACRO, the idea is to replace police on certain noncriminal emergency calls—welfare checks, disoriented person reports, found juveniles—with teams of EMTs and “intervention specialists.” They’ll provide food, water, and emergency medical care, transport clients to family homes or safe places to stay, and connect them with social services, says deputy fire chief Melinda Drayton, who’s been working out the details of the program.

All of it, Drayton says, will be based on the principle of consent, as well as MACRO teams’ connections with the people they’re serving: “We’re really looking to have some level of either lived experience, familial experience, some deep connection to the streets of Oakland.” She’s seen 911 calls stack up in OPD’s dispatch center; she gets that many people served by MACRO won’t trust city authorities. To succeed, she says, MACRO teams will need strong relationships with the organizations and people already working to respond to neighborhood crises.

Police, according to Drayton, haven’t put up any opposition. “You’ll get the cheeky response, like, ‘I think you’re going to end up having to call us.’ And I’m like, ‘Hey, we don’t know until we know.’”

Ruiz and other protesters shut down the intersection near where Hogg was killed in 2015.

Courtesy of Rebecca Ruiz

The incident on East 25th is an opportunity to see how community intervention can play out in real time. Some activists in Oakland, like Jasmine Williams of the Black Organizing Project, believe the incident with Jones is proof of “We keep us safe.” To these observers, Jones survived only due to the intervention of APTP and his family. To Brooks, Jones’ encounter with police offers at least a temporary path forward. “For us to be able to communicate with the police, police to communicate with us, to be able to negotiate him being talked down by someone he loves—it was awesome,” she says. She’s still going to keep working to defund police and build up alternatives like MH First. But “if this is how it’s going to be for a few years,” she adds, “this is how it should go down.”

It’s impossible to say with certainty what would have happened if APTP had never responded to the scene of Jones’ crash, pressuring police to deescalate and get Jones medical attention. Armstrong, the police chief, insists that if Jones’ mother had never been identified to officers, the police would “have stood there as long as we needed to,” brought in more cops with crisis intervention or tactical negotiation training, or summoned a clinician from the county’s social services department. “We would have waited as many hours at it took for us to get a safe resolution,” Armstrong tells me.

He credits police policy and training, as well as a new sense of openness in his department to accepting civilian help, for the outcome of the encounter with Jones. “It doesn’t matter to me if it’s the Anti Police-Terror Project,” he tells me. “If it’s making Oakland safer, if it’s allowing people to resolve issues without law enforcement intervention, I’m in full support.” With Jones, his officers “did what they were trained to do, which is retreated and created time and distance, and begin to go through the process outlined in our policy,” he told members of the Oakland police commission, a civilian oversight board, two days after the incident. In his presentation, Armstrong emphasized it was “not uncommon” for incidents like the one with Jones to lead to a “safe resolution.”

But the policy and training the chief was referring to were enacted only at the urging of a federal judge, as a direct result of yet another OPD shooting. Three years after Hogg was killed, OPD killed another person under similar circumstances: Joshua Pawlik, a 31-year-old unhoused white man. Described by a friend as a “free-loving hippie,” Pawlik was asleep with a gun between two North Oakland homes when police approached him, woke him, and killed him.

A 2015 protest of Hogg’s shooting

Courtesy of Rebecca Ruiz

Whereas Hogg’s death had produced only “lip service” from the OPD about reform, and a citizen’s police review board cleared officers of wrongdoing, Burris says that the circumstances around the Pawlik shooting—four officers fired 22 bullets from behind their BearCat—led to more substantial changes in the department. OPD is under the oversight of a monitor appointed by a federal judge as part of a settlement between Oakland and defendants in an early-2000s police misconduct lawsuit, in which a group of cops dubbed the “Riders” were accused of kidnapping, beating, and planting evidence on 119 people, mostly Black men. The monitor reviewed the Pawlik case and slammed OPD’s “incompetence and dishonesty” in the shooting. In response, the federal judge urged the department to implement a policy they’d slowly been developing, specifically for encounters with unresponsive, potentially armed people.

It took almost two years, but the final policy was approved by Oakland’s police commission this January. It emphasizes some of the same demands Brooks made of police on East 25th Street: time, space, deescalation. Officers must prioritize the preservation of life. And they must consider whether the unresponsive person is a member of a “vulnerable population” who may struggle to understand or comply with orders.

It does allow them to use guns. “We are dealing with the armed suspect, and so we have to be prepared for anything that may occur,” Armstrong says in an interview. “While we don’t want these things to end tragically, we also want to make sure that for whatever reason, if the person decided to step out of the vehicle and shoot, or seek to harm someone, that we would be prepared to respond.”

If Jones, struggling awake in the hatchback, would have posed a public threat, we’ll never know. When I ask Burris if he’s ever heard of a police encounter in which someone sleeping with a gun woke up shooting, he answers simply: “No.”

Webb-Breaux doesn’t buy Armstrong’s confidence that the cops could have handled the situation. Sometimes, at night, she still hears police guns clicking. “They were ready,” she believes. Ready to kill him. She says APTP saved her son’s life: “They were the extra eyes.” Without witnesses, she says, the police “wouldn’t have spent all that time trying to get him out the car. They would have just shot him and gone on about their day.”

Lieu still struggles with her decision to call 911 on Jones. Not until our third conversation does she tell me she was the one who contacted authorities. “I didn’t know if he had a gun,” she says. “I didn’t know anything. I just knew that he was passed out. And I had no idea that the response was going to be so many officers.”

After Jones left his car and hugged his son, he was brought to the hospital in an ambulance, then transferred to the county jail. A prosecutor charged him with seven felonies for the events of that morning, all related to the fact that he had a gun in his car and a prior felony on his record. He took a plea deal and was sentenced to six months in jail, where attempts to contact him for this story were unsuccessful. “As of now, since I’ve been here, I’m really working on a transition in myself,” Jones told the judge during his sentencing hearing, appearing on a video feed from Santa Rita Jail. “I don’t want to keep going through the same recidivism program process.”

For Ruiz, the MH First volunteer, this outcome is a source of inner conflict because Jones was still sucked into the system of court and jail. “There’s part of this that feels really, really good—that this person wasn’t killed by the police,” she says. “And also, Santa Rita is the most dangerous place to be in Alameda County. Especially if someone’s going through a mental health crisis.”

Yet Ruiz isn’t immediately sure of what she would have done if she’d been the one to find Jones unconscious in his car. After some deliberation, she texts me to say she probably would have done nothing at all: “It’s likely Lavel and Demouria would have slept then woke up and then just drove home.” If the car was in the middle of the street, Ruiz says, she’d offer help and ask the driver if they were okay—gun be damned. “For me, the project of [MH First] is one of radical empathy—to think of what we would want if we were the person passed out with a gun in the car,” Ruiz says. “I would want to be approached with compassion and support.” Calling 911, to her, is a problem, not a solution.

The alternatives to police currently emerging in Oakland don’t offer blanket answers, either. When MACRO launches, emergency calls involving guns will be considered “too hot” for their teams to handle solo, Drayton warns. “We’re not going on the suicidal subject. We’re not going on the man with a gun unconscious in the car. We haven’t figured that out—yet.”

Perhaps MH First will take the call instead. “We need it all,” Brooks tells me. MACRO, MH First, still-to-be-imagined alternatives. There will always be a need for “something” to respond to emergencies, Brooks believes: “There’s too much trauma, too much wounding, white supremacy has done too much damage.” But that something—whatever it is—“looks very different than what we have now.”