More than five years ago, the MeToo movement exploded and our culture shifted. But what actually changed? This project seeks to reexamine the era by asking how it will alter the lives of the next generation.

In 2015, Celeste Blair was sentenced to 30 years in prison for a drug crime. Blair, now 53, had experienced a series of heart-wrenching relationships with abusive men—from childhood to adulthood, both inside and outside of correctional facilities. These shaped and contributed to her addiction, she says. As MeToo rose, Blair began to ask: Could her life have turned out differently if the movement had started sooner? “Perhaps I would even be free,” she wonders.

I get to prison, and I’m realizing something has to be very wrong with my cognition. Something is not right with my brain: I’ve just thrown away my whole life over a bunch of dumb shit.

It was then I start hearing about the MeToo movement. It started showing up on Ellen, and on NPR. They started talking about Epstein and Harvey Weinstein. I remember thinking how different my life would have been if that had not come so late.

Around the same time, I was taking a class in victimology, criminology, and sociology, and came upon this thing called the Power and Control Wheel. It’s put out by the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. Basically, it’s a picture of a wheel. In the middle it says “power and control,” and then around the edge of the wheel it says “physical and sexual violence,” and then it goes around like cogs of the wheel. “Intimidation,” that’s how it starts, but it goes around to “emotional abuse, isolation, minimizing, economic abuse, male privilege, coercion, and threats.” I know that in my life, in my interactions with men, I’ve been spun on that wheel, just like Russian roulette. It was the norm. That’s just the way it was. And I can’t believe it took so many years to make it where it was not an acceptable manner of operations anymore.

So I started showing other women this wheel, and I’m telling them, “Listen, you don’t have to be part of that. If a man tells you that your friends and family are not up to par, and that he just wants you to be with him all the time, that’s a red flag. That’s not passion and love. That’s unhealthy. And you have to know these things.” I just wish somebody had taught me that when I was younger.

I had a pretty interesting childhood. I guess we all did, right? I was born in Jacksonville, Florida, but I lived wherever my daddy was: in Berkeley, California, or in Abaco, Bahamas, or in Jacksonville. It was the ’70s, so my daddy rode a Harley and grew marijuana, made acid in the basement. They were doing big avant-garde things, and he was telling me to not ever get caught up in the rat race. He also taught me to be an artist and treated me like an adult. I was a real daddy’s girl.

But my father, he was just a bit wild. Although he was never violent toward me, I know he was very violent toward my mother. She left one day when I was young, said she was going shopping and didn’t come back. About a year later, she and my uncle came and picked me up off the street and didn’t tell me where I was going. They didn’t tell Daddy they were taking me to Fort Worth. It was traumatic; I would not stop crying. When I was 11, my daddy kidnapped me back. I stayed with him for a while, then went back to my mom.

Celeste Blair around age 10

Photo courtesy Blair’s family

When I was 15 in Fort Worth, I was raped. That was the most pivotal moment of my life. I was babysitting at this house, and the oldest brother, who was like 17, came home drunk and forced himself on me. I don’t remember the details. I think I blocked it out. I do know I became pregnant. I didn’t tell a soul, not one single solitary person. My stepdad was a musician, so he and my mom were always on the road; I was able to fly under the radar and carry a baby to full term without anyone knowing. The day I gave birth, it was all so taboo that my mom made it seem as if I’d been in an accident on the way to school—that was the cover story. The nurse who delivered him adopted him within 48 hours. I remember holding him in my arms—he was so beautiful—and breathing him in, just trying to absorb him into me and say goodbye.

Giving the child up for adoption contributed to me turning toward drugs. I dropped out of high school. All the things I thought were in my future, like going to school to be an architect or a designer, flew out the window. I lost my path. When my daddy died in 1989, the drug usage went overnight from something that was fun to something that kept me alive. Eventually I married and settled down and tried to focus on my art, but every once in a while I’d still party.

I ended up at this bar with this guy who bought me seven Mind Erasers and told me he owned six warehouses and wanted to hire me to do murals. He says, “I’ve been doing some of this cocaine and would like to know what’s up with it. How much would a kilo be?” I said, drunk, “I don’t know, probably $10,000 and a pair of those cowboy boots.” I was trying to please him because I wanted this gig. I got 25 years.

I went to prison in Texas. It was the early 1990s. I was there pending parole, but there was no parole officer on the unit. One day, this guy comes and he’s like seven feet tall. He comes in and we start trying to connect with him, me and my friends, because we need our papers done, and he’s the person who has to process all that through Austin and get you released.

I go talk to him and I realize he’s a little bit off. He had just come back from Bosnia. He was calling myself and the other five white girls into his office on a weekly basis and talking about our titties and all the things he’d like to do to us, and just being extremely inappropriate. But what am I supposed to do? He’s holding a file with all my information, and he is my only connection to the free world. So I would just try to appease him.

This went on for maybe two months before things began to get crazy. There was a girl, I guess she worked maintenance for the captain or the captain’s orderly. At some point, she writes a grievance. But nepotism runs rampant in these prisons. She had no way of knowing that his mother was the grievance lieutenant. His mother was asking him, “What’s going on with you and these girls?” He didn’t know who was writing him up, so he starts coming to work like psycho mode, telling each of us, “I will shoot you from the top of this fucking mountain while you’re exercising on the rec yard. I know your schedule.” And he had pictures on his office wall of him with these huge guns from Bosnia, from Desert Storm. He was like, “I will kill your whole fucking family if you don’t quit fucking with me.” And we’re like, “What are you talking about?” Because we didn’t know the girl who was writing him up, we didn’t know what was going on. At the same time, he’s getting more escalated, kind of like he knew the cat was out of the bag and he was gonna get all the kicks he could. I went into his office one day and he pulled his dick out onto the desk and started hitting it with a ruler, as he was talking to me about whatever. I was appalled. I just wanted to get out of there.

So as it would happen, the girl who wrote the grievance, she went to the captain, and the captain had Internal Affairs put a wire on her. When Internal Affairs kicked in his door, he was jacking off in a trash can and she was getting up from her knees. They walked him off the compound and called us to an interview at the commander’s office. I was like, “Listen, I’m not gonna tell you anything from in here. When I get out, I’ll tell you whatever I want with my lawyer present, but I’ve known too many girls that ended up disappearing into a hole and never coming out in that situation in Texas.” So I chose to wait till I got home, which was only a month later, and went to an attorney. We put the prison on notice for a lawsuit. There were about 11 girls, and they paid us $4.1 million as a group. I didn’t get very much money because of what’s called “proper notification”: If you never told them, they aren’t responsible. I was among the very first ones to be abused by him and I didn’t tell anybody [in prison as it was happening], so I didn’t get the settlement.

Blair and her mother

Photo courtesy of Blair’s family

When this lawsuit happened, the same girl who had the wire on happened to be from Austin. Her husband was showing up at the capital all the time, like, “Hey, my wife in prison was sexually assaulted by a parole office, and I want answers.” George Bush assigned a special prosecutor named Gina DeBottis who investigated. When Bush went on right afterward to be the president of the United States, one of the first things he did was sign the PREA executive order. And later, after I violated my parole for a technical reason, I had to go through this PREA training and it dawned on me that because of our voices we had made a positive change. I was just overwhelmed with joy knowing that.

But the problem was that because of all this stuff that happened, I felt dirty, and just from the whole prison experience I couldn’t reintegrate with my life properly. My husband, Lee, had spent the prior years getting educated and becoming a professional, and I walked in and felt as if I didn’t fit. They literally degraded me to the point that I felt like I was a convict and nothing more; our marriage didn’t last much longer.

At the same time, I was getting hyperaware of everything my daddy had taught me about nature and how we have to give back to the Earth. When I met my next husband, he showed me this place, the House of Yahweh, where there were little girls that were making stuff out of wool that their brothers had sheared, and they were kosher-killing animals that were grass fed and clean, and making cheese and eggs that could be eaten without worrying about this chicken’s life.

I thought I had found a safe space, but it was all bullshit in the end. One day, one of my duties was to check people into the front of the synagogue or sanctuary during the feast, and a woman I worked with whispers to me, “Will you be participating in the ear-awling ceremony today?” And I was like, “What is that?” And she told me I should go ask my husband. I went home and he was like, “According to Scripture, you can nail your ear to the sanctuary door, and you will show that you’re going to worship Pastor [Hawkins] forever.” And I was like, “That is a dealbreaker for me. Y’all just crossed a line.” It never occurred to me that his counselor there who had a serious grip on him would demand that he divorce me immediately if I wasn’t going to be part of the House of Yahweh anymore. I was devastated, because I thought he and I had something else. That kind of spun me out of control, or I allowed that to spin me out of control.

After the divorce, I relapsed, had a midlife crisis over it, and ended up beginning this weird relationship with a man that was based on drugs, based on the escape of the circumstances of our life at the time. He got arrested after I introduced him to someone, and they sat him down in a room and said, “How do you know this guy that you just did a drug deal with?” The answer was me. I got 30 years. That was in 2015.

When I looked back and reviewed all the things that could have been better, what that did for me is spark this obligation, because of my age, to pass on my experiences so that the women I’m in contact with can see they don’t have to do it the way I did it, they don’t have to be a pawn for men in order to succeed or survive.

I’m hoping my granddaughter and my nieces are living in this new world where a girl has a lot more say: She has a counselor at school or someone she can talk to. Or she can put him on blast on social media. While the internet has its dangers, I think it’s opened up a way, obviously through the MeToo movement, for a young girl to protect herself and expose a guy for being the scumbag he is if he’s overly fresh. The guy that raped me? I would have put his ass on blast on the internet, had that been available at the time.

What’s funny is, before we had our phone call, I took my little notebook out to the rec yard, and I asked a few of the girls out there, “What do you think about the MeToo movement?” A lot of these girls don’t know what that is. And so I explained it to them and asked, “Do you think that has affected your life?” And they’re like, “Well, I want it to.” [Laughs]. I was like, “Well, I think it’s going to.”

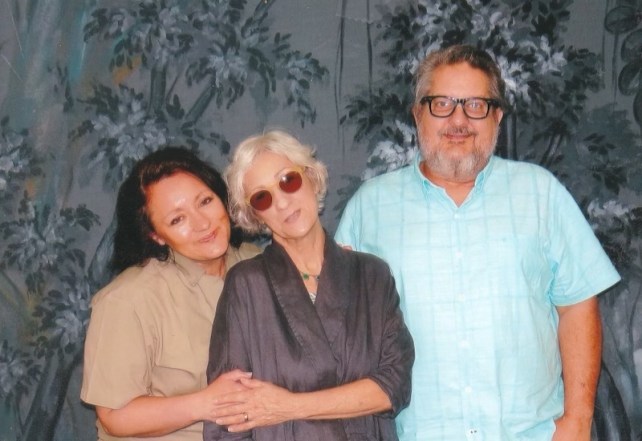

Blair during a prison visit with her mother and stepfather

Photo courtesy of Blair’s family