It was quite the messaging turnaround. In his September 6 acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, President Obama—whose reticence about so much as mentioning global warming has flummoxed environmental activists—used the subject to launch an unexpected attack on his opponent. “Climate change is not a hoax,” the president declared. “More droughts and floods and wildfires are not a joke. They are a threat to our children’s future.” In the after-speech gabfest, Politico cited the moment as one of Obama’s top applause lines.

Obama’s shift comes as pollsters and strategists are increasingly saying that Democrats—and even perhaps some Republicans—could be using the climate issue to their political advantage, especially after a summer of drought, wildfires, and record heat. Ever since the collapse of cap and trade, it’s been “strong conventional wisdom, even within major environmental organizations, that it can hurt us to talk about climate change,” explains climate strategist Betsy Taylor, whose consulting firm Breakthrough Strategies and Solutions just released a new report on the subject. “And I think that was a mistake.”

The conventional wisdom that activists like Taylor want to upset emerged following the 2008 economic collapse—when many climate advocates were painted as wannabe energy taxers, and a sharp contrast was drawn between helping the economy and helping the climate. Then came “Climategate,” a pseudo-scandal which has since been debunked, but which planted the idea that climate scientists had made up results to scare the public, and weakened Americans’ concern about global warming. Upshot: In the 2010 congressional elections, a number of Democrats who’d voted for cap-and-trade were picked off by Republican challengers. The most prominent victim: Virginia’s Rick Boucher, a 14-term congressional vet who lost to a tea party opponent who’d pilloried his pro-cap-and-trade vote. Moderate Republicans known for taking climate change seriously, like former South Carolina Rep. Bob Inglis, were also sent packing.

Recent polling data make clear, however, that extreme weather is leaving Americans increasingly worried about climate change. A mid July survey from the University of Texas-Austin, for instance, found that 70 percent of the public thought climate change was happening, an increase from 65 percent in March. What’s more, a series of public opinion reports and analyses—some based on data collected prior to the record heat waves of the summer, which suggests the public is even more alarmed now than when those surveys reached them—have indicated that global warming is a potential political winner, rather than an electoral albatross.

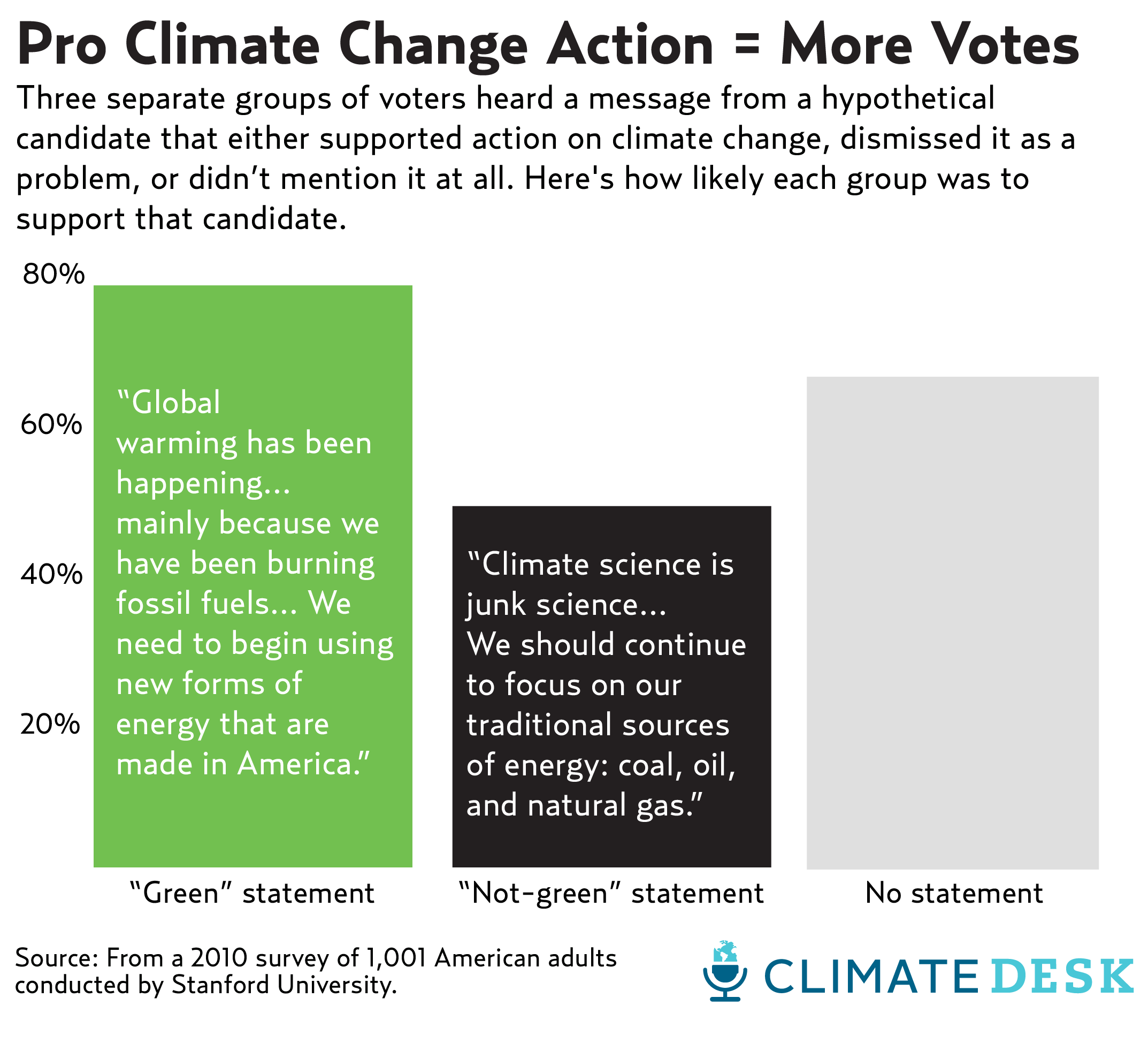

The first of these studies emerged in 2011 from Stanford pollster Jon Krosnick and his colleagues. The researchers conducted a survey in which respondents were broken into three groups, and then asked to support a hypothetical Senate candidate who either (1) denied the science of global warming and attacked cap and trade, (2) accepted the science and called for action, or (3) took no position on the issue. The result was clear: 77 percent of respondents supported the “green” candidate, 65 percent the neutral candidate, and only 48 percent the denier candidate. Both Democrats and independents strongly favored a green candidate over a neutral one, while for Republicans it was basically a wash—neither a pro- nor an anti-climate candidate moved them much. “By taking a green position on climate, candidates of either party can gain votes,” Krosnick’s team concluded.

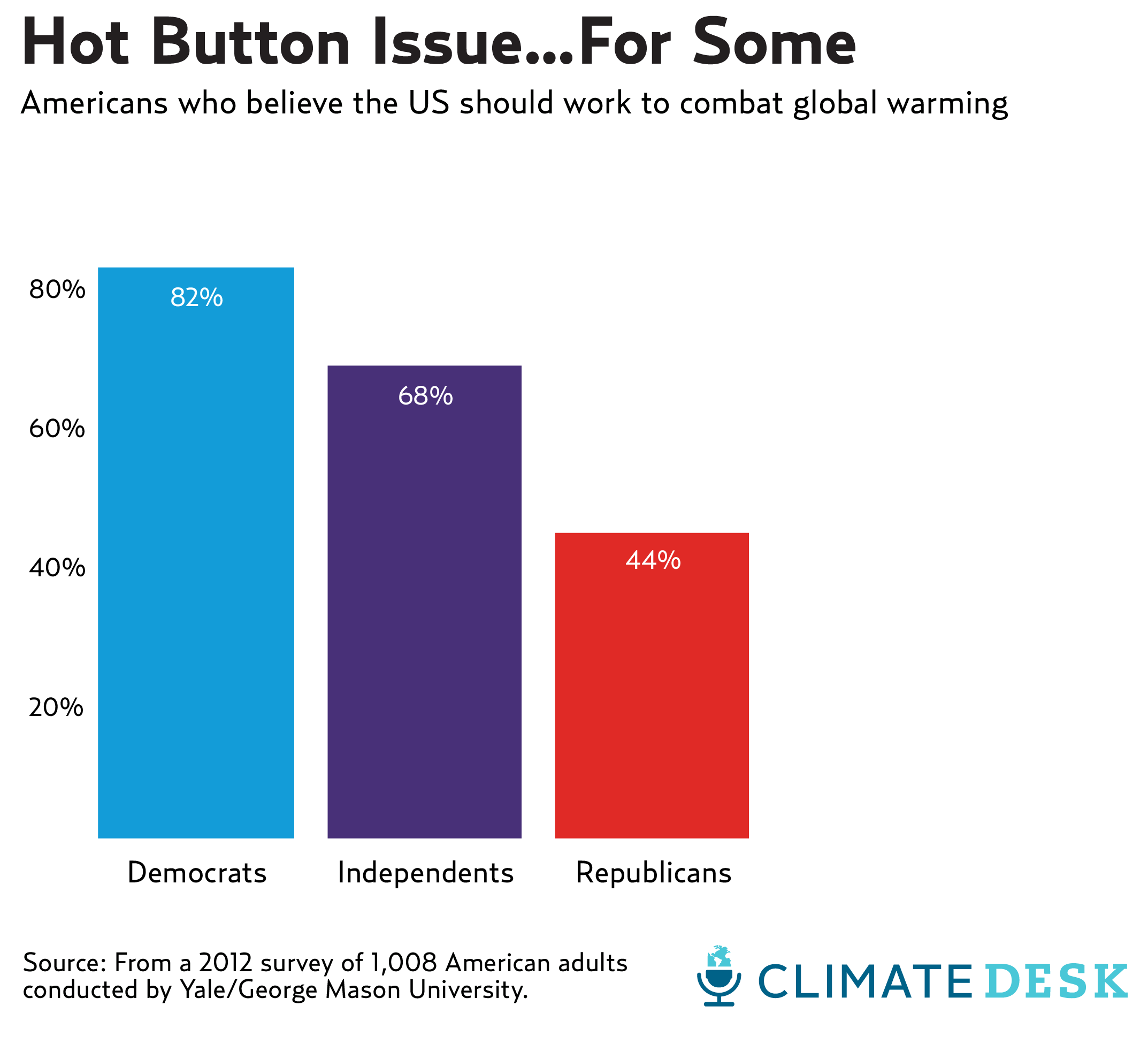

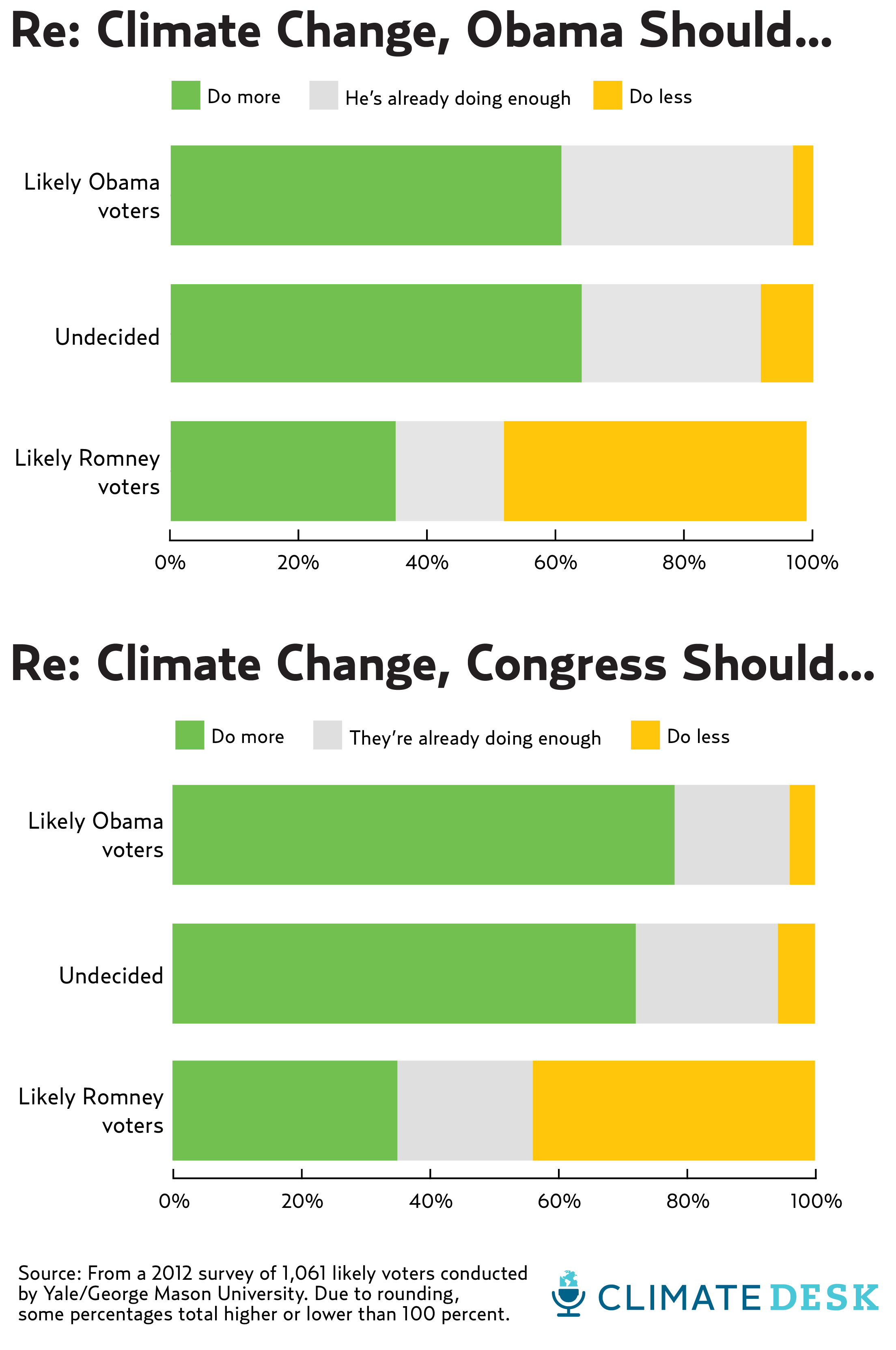

Their findings were reinforced earlier this year by researchers at Yale and George Mason University who, in a March 2012 survey, similarly found that taking a stand on climate has the potential to motivate Democratic and independent voters, without causing damage among Republicans. For instance, 82 percent of Democrats and 68 percent of independents agreed that the United States should undertake an either medium- or large-scale effort to cut down global warming.

The implication, explains Edward Maibach of the George Mason Center for Climate Change Communication, is “so different from what seems to be the wisdom of politicos, which is that this is a third rail of politics and you don’t touch it.”

The reason, he explains, is that “independents respond more like Democrats than like Republicans” on the issue—giving climate advocates a potentially larger base of support. For example: 72 percent of Democrats in the study, as well as 66 percent of independents, agreed that global warming would harm “future generations” either a moderate amount or a great deal.

But perhaps most striking is Taylor’s recently released report, which draws on a survey designed by Harstad Strategic Research pollster Andrew Maxfield, who previously did polling for President Obama’s 2008 campaign. In a survey of 1,204 likely voters in May 2012, Maxfield found that a “clean energy” candidate fared better than an “all-of-the-above” candidate who supported a variety of energy choices—coal, drilling, and also clean energy.

Maxfield then went on to test a variety of climate messages—and the upshot, he says, is that “if you feel strongly about climate change, there is a way to talk about it that voters will understand and appreciate”—especially if candidates focus on recent extreme weather. “I was surprised at the strength of that, and the extent to which voters had begun to recognize the severe weather, and experience it,” Maxfield says. It helps that climate scientists themselves are increasingly outspoken about explaining that global warming is shifting the odds in favor of more heat waves, severe storms, and other weather extremes—even if no single, isolated event can be laid at the feet of global warming.

Another set of messages Maxfield tested involve oil companies, which people perceive as having too much power. “They know that oil companies command undue influence” and “have rigged the system in many ways,” says Maxfield. He and Taylor advise emphasizing “patriotic pride”: America can come up with climate solutions—it can “rise to the challenge and succeed.” Such messaging, they suggest, can appeal to a “solid majority of voters.”

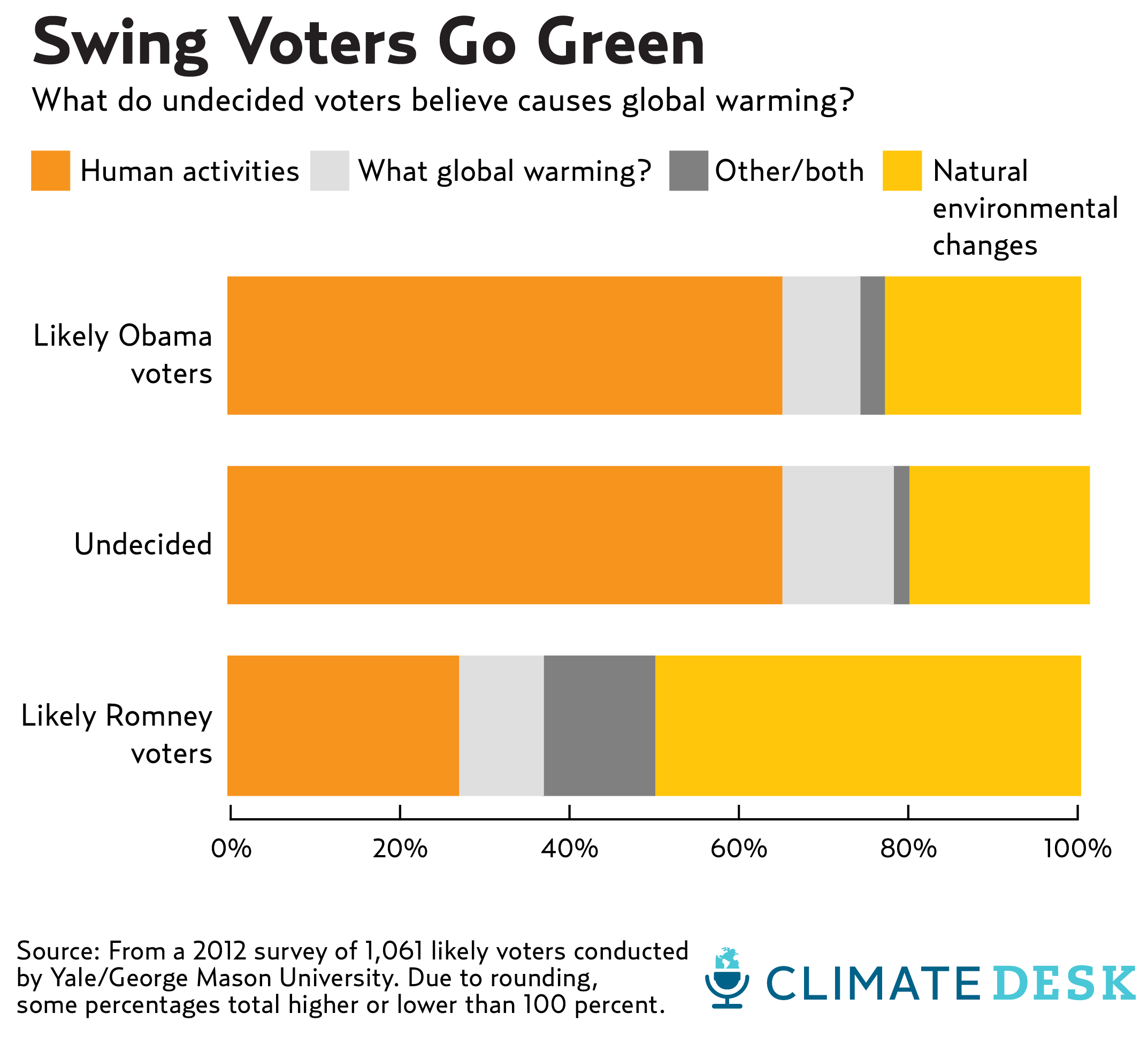

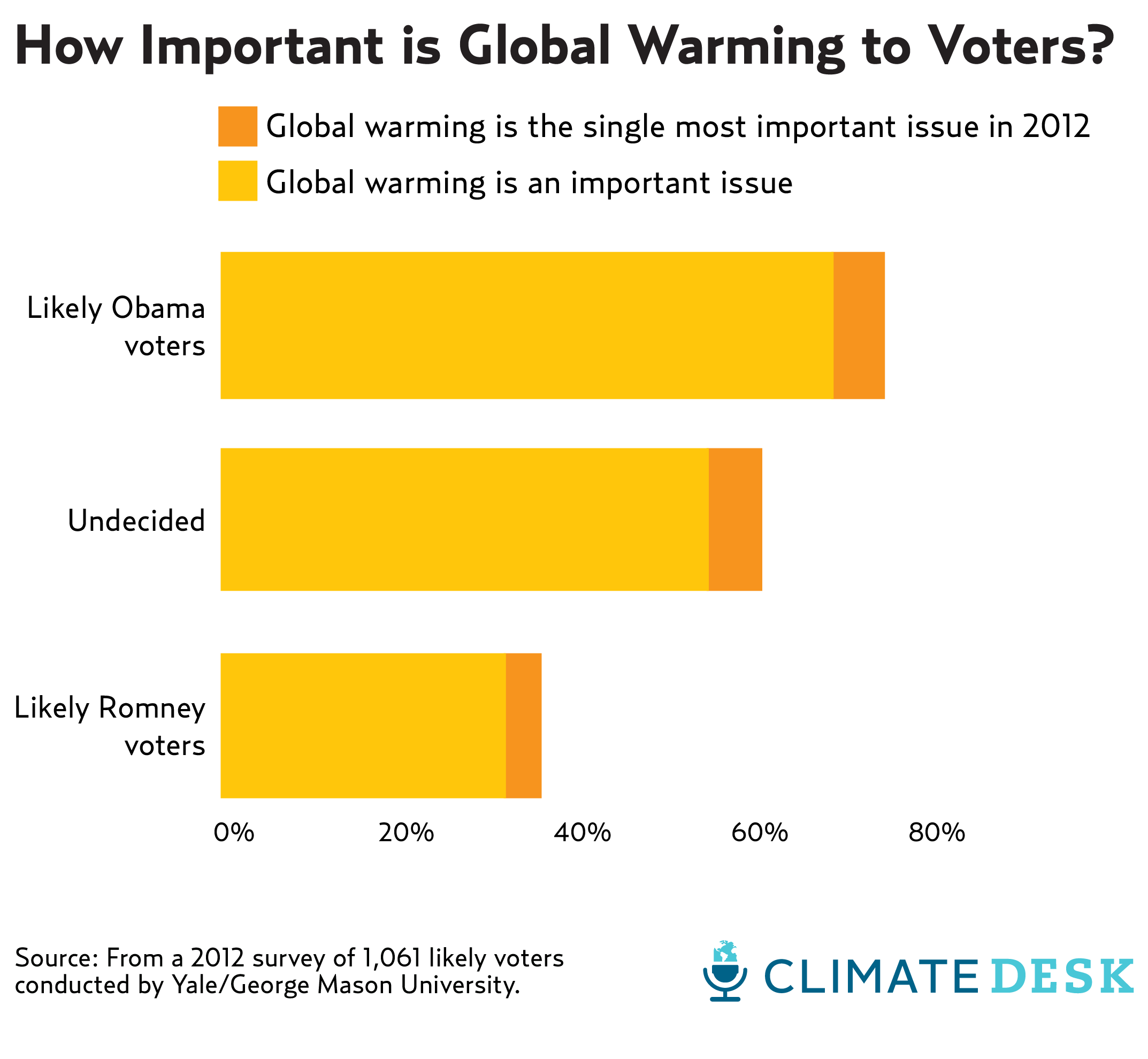

What’s perhaps most fascinating is that all three studies discussed above are based on public opinion data gathered prior to the summer of 2012, when record heat and freak storms drove up public belief in global warming. The Yale and George Mason group just conducted another more recent poll, this one on likely but undecided voters in the 2012 election. Not only do most undecideds think global warming is happening and caused by humans, but 61 percent say it will be an important issue in determining who they vote for.

To be sure, none of the pollsters or strategists are saying that climate change will be a winning issue across the board. There are good ways and bad ways for politicians to communicate about climate, explains Paul Bledsoe, a Washington-based consultant who was the chief staffer on climate change communications in the Clinton White House. “When it is isolated from the things they care about, people tend to react more negatively, especially if they feel they’re being lectured about it, because they often feel there’s little they can do about it,” Bledsoe says. Rather, he explains, a climate message will resonate with voters if it is made “relevant to their livelihoods, experiences in their states and localities.”

In other words, it is not that any type of climate communication is a guaranteed win—just that it is far from a guaranteed loser. But that still leaves a growing disconnect between politicians’ fear of the climate issue on the one hand, and emerging public opinion data on the other. “Democrats don’t need to be as afraid of this issue as they are,” Maxfield says. From President Obama on down, if candidates who talk about climate change win in 2012, expect that situation to rapidly change.