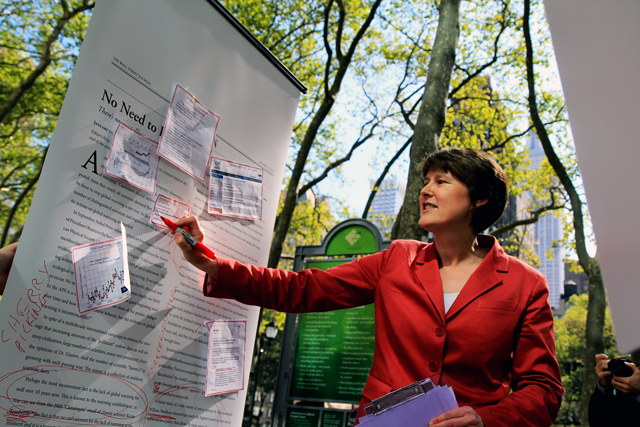

Last month, the University of Virginia won a legal battle to protect the private emails of one of its former researchers. The records had been requested by a group critical of the scientific consensus on global warming.

The close of the 20-month public records fight brought interesting documents to light—including some suggesting that one of the group’s lawyers had misrepresented his employment status, and had been fighting the case while working a federal job, a potential violation of ethics rules.

On September 17, Judge Paul Sheridan of the Prince William County Circuit Court ruled that the Virginia Freedom of Information Act did not apply to data and records created in the course of scholarship. The decision barred the American Tradition Institute, a “free-market”-minded think tank, from accessing the emails of Michael Mann, a well-known climate scientist who previously worked at the University of Virginia.

Mann, now the director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University, is the co-author of a widely-cited paper that included the so-called “hockey stick” chart documenting the uptick of global temperatures in the industrial age.

His work has long made him the subject of attacks from climate change deniers. But things ramped up in 2009 when over one thousand stolen emails between climate scientists, including some sent by Mann, were released. While at least nine academic and governmental investigations have exonerated the scientists, climate skeptics argued that the emails revealed a conspiracy to fix data, most notably around his famous chart. In the wake of that kerfuffle, others have sought to access Mann’s inbox through legal means.

In 2010, a judge rebuffed a subpoena from Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, a Republican and a climate change skeptic, for Mann’s emails. Then in January 2011, ATI made its request under the state’s open records law, on behalf of itself and state Delegate Robert Marshall, another vocal climate change critic. University of Virginia, ATI, and Mann’s lawyer have been wrangling over the information ever since.

ATI has offices in Colorado and Washington, DC, and is closely affiliated with the American Tradition Partnership, a 501(c)4 that bills itself as “a no-compromise grassroots organization dedicated to fighting the radical environmentalist agenda.” As the Institute for Southern Studies has documented, both groups and the people involved with them have extensive ties to energy interests and have led other attacks on climate science and renewable energy.

ATI’s network includes very well-known climate deniers, like Chris Horner, who serves as the director of litigation for ATI’s Environmental Law Center. He’s also a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute and a frequent contributor to right-wing blogs. The director of ATI’s Environmental Law Center, David Schnare, worked at the Environmental Protection Agency for 33 years, most recently as a senior attorney.

In ATI’s suit seeking Mann’s emails, those two lawyers argued that the work—including the email correspondence—of any scientist at a state university or federal agency should be subject to open records laws.

In May 2011, UVA and ATI had entered into a protective order that would have allowed ATI’s lawyers—Schnare and Horner—to review the records in order to contest their withholding, on the condition that the information not be shared. UVA president Teresa Sullivan said the school would use “all available exemptions” to protect academic freedom.

According to Megan Rhyne, the executive director of the Virginia Coalition for Open Government, this arrangement allowing ATI’s attorneys full review of the documents was very unusual. And the university was particularly troubled that Horner and Schnare were ATI officials who were deeply involved in anti-climate science circles, and not merely hired outside counsel. With the risk that they might share information in the documents in mind, in October 2011, UVA’s lawyer filed an affidavit with the court, citing “disturbingly inaccurate” information in the press that seemed to have originated with Schnare and Horner about the protective order. They also noted that Delegate Marshall, who was not permitted to see the claimed exemptions, had told the Washington Times that he wanted “to look at what they’ve given us and examine what they’ve withheld and see why it’s been withheld,” which would be a clear violation of the terms of the protective order.

The school asked to modify the order noting it had “developed increasing concerns about the reasonableness of its agreement to allow these two individuals access to exempt records.” The school feared that the pair would not review the documents as disinterested legal experts, but would use the information to advance the political mission of ATI and to attack Mann. In its request to modify the order, UVA also noted additional information they’d received since May that had raised alarms about whether ATI’s lawyers were being entirely honest. In particular, the school felt that Schnare had misrepresented himself by claiming that he had already left his job at the EPA when this order was issued back in May. In fact, Schnare noted in an email to UVA’s lawyers dated September 29, 2011 (included as Exhibit 21 here) that he was only leaving his job the next day—September 30.

Working for ATI while at EPA isn’t in itself a problem, necessarily: ethics rules allow federal lawyers to do pro bono work, provided they receive permission and that they only conduct that business outside of work hours and work facilities.

In court documents, Schnare says he sought prior permission from the EPA. But UVA provided the court a letter from the EPA that, while acknowledging such a memo from Schnare, says its first record of that memo is also from September 2011—when Schnare provided it in response to a media request, and after Schnare had been seeking the documents on ATI’s behalf for nine months. The EPA’s letter (included as Exhibit 26 here) raises some questions regarding his approval request:

The request for approval of the outside activity was purportedly prepared by Mr. Schnare on or about November 16, 2010, but neither his Deputy Ethics Official nor his Assistant Deputy Ethics Official has any record of receiving it or approving this request to engage in outside activity.

In its court filing, UVA raises concerns that Schnare’s letter “may have been prepared after the fact.” The university’s lawyers also note that the memo refers to the American Tradition Institute, even though at the time that memo had purportedly been drafted the organization was actually known as the “Western Tradition Institute.” UVA’s filing goes on to note that even if Schnare did have permission from EPA, “he frequently and consistently communicated with counsel for the University and its Public Records officer during regular weekday business hours,” and provides time stamped emails to back up that assertion.

UVA concludes in its filing that:

University counsel can no longer defend their willingness to entrust tens of thousands of pages of personal, scholarly, and research communications from Professor Mann and other scientists to two individuals who have regrettably provided far too many reasons to doubt that their words may be trusted.

ATI responded with a filing disparaging UVA’s argument as a discourteous and “error-filled personal attack.” It argued that his request had been properly filed but lost in the EPA bureaucracy, and provided a computer printout purporting to show that the document had been created in November 2010 (exhibit 5). While ATI’s response includes a copy of the contested permission memo where Schnare pledges not to do any work on the case using EPA equipment or during working hours, it does not address UVA’s time stamped emails suggesting he may have. Nor does it address the issue of the American Tradition Institute’s name change. (The EPA’s press office did not respond to multiple requests to comment on Schnare’s employment status and permission to do outside work.)

Schnare insisted in an interview with Mother Jones that he had proper authorization to litigate the email case. “I had permission to do legal work outside of work that did not directly involve the EPA or issues in front of the EPA and this is one of them,” he said. He added that the work was pro bono and insisted it was done outside of his day job.

While the court’s ruling on Mann’s emails didn’t touch on ATI’s motivations or Schnare’s employment, the legal record suggests that ATI’s own lawyer may have been working on the case while at has taxpayer-funded EPA job. Wherever and whenever Schnare did his lawyering, ATI’s main argument for why they should have had access the emails was to “fulfill the public’s right to know how taxpayer-funded employees use the taxpayer’s resources.”

Peter Fontaine, the lawyer representing Mann in the case, called the court’s decision a victory for science. “Scientists and public universities across the United States are under attack by industry-funded attack groups who seek to confuse the public about the scientific facts on climate change,” he said. “But rather than engage in an honest debate over the facts, such groups attempt to chill scientific research itself by using public records laws to tie-up faculty and university resources by filing FOIA requests seeking faculty correspondence, which they want to ‘crowd-source’ on the world wide web.”

Schnare told Mother Jones that the group will most likely appeal the decision to the Virginia Supreme Court. In the meantime, ATI has broadened its records-law tactic to include the emails of other prominent climate scientists like Texas A&M University’s Andrew Dessler and Texas Tech’s Katharine Hayhoe, including their correspondence with reporters. Environmental and academic groups, as well as other climate scientists, say ATI is again using this tool to intimidate and burden scientists.