This story first appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The Mississippi as seen from Ed Drager’s tug boat is a river in retreat: a giant beached barge is stranded where the water dropped, with sand bars springing into view. The floating barge office where the tug boat captain reports for duty is tilted like a funhouse. One side now rests on the exposed shore. “I’ve never seen the river this low,” Drager said. “It’s weird.”

The worst drought in half a century has brought water levels in the Mississippi close to historic lows and could shut down all shipping in a matter of weeks—unless Barack Obama takes extraordinary measures.

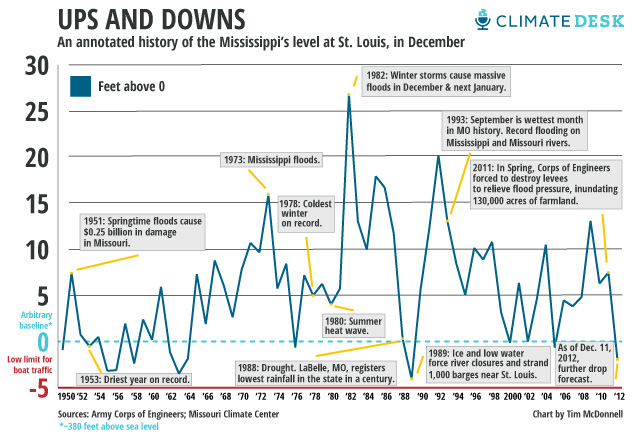

It’s the second extreme event on the river in 18 months, after flooding in the spring of 2011 forced thousands to flee their homes.

Without rain, water levels on the Mississippi are projected to reach historic lows this month, the national weather service said in its latest four-week forecast.

“All the ingredients for us getting to an all-time record low are certainly in place,” said Mark Fuchs, a hydrologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in St. Louis. “I would be very surprised if we didn’t set a record this winter.”

The drought has already created a low-water choke point south of St. Louis, near the town of Thebes, where pinnacles of rock extend upwards from the river bottom making passage treacherous.

Shipping companies are hauling 15 barges at a time instead of a typical string of 25, because the bigger runs are too big for current operating conditions.

Barges are being sent off with lighter loads, making for more traffic, with more delays and backups. Stretches of the river are now reduced to one-way traffic. A long cold spell could make navigation even trickier: shallow, slow-moving water is more likely to get clogged up with ice.

Current projections suggest water levels could drop too low to send barges through Thebes before the new year—unless there is heavy rainfall.

Local television in St. Louis is already dispensing doom-laden warnings about rusting metal and hazardous materials exposed by the receding waters.

Shipping companies say the economic consequences of a shutdown on the Mississippi would be devastating. About $7 billion in vital commodities typically moves on the river at this time of year—including grain, coal, heating oil, and cement.

Cutting off the transport route would be a disaster that would resonate across the Midwest and beyond.

“There are so many issues at stake here,” said George Foster, owner of JB Marine Services. “There is so much that moves on the river, not just coal and grain products, but you’ve got cement, steel for construction, chemicals for manufacturing plants, petroleum plants, heating oil. All those things move on the waterways, so if it shuts down you’ve got a huge stop of commerce.”

Local companies which depend on the river to ship their goods are already talking about layoffs, if the Mississippi closes to navigation. Those were just the first casualties, Foster said. “It is going to affect the people at the grocery store, at the gas pump, with home construction, and so forth.”

And it’s going to fall especially hard on farmers, who took a heavy hit during the drought and who rely on the Mississippi to ship their grain to export markets.

Farmers in the area typically lost up to three-quarters of their corn and soy bean crops to this year’s drought. Old-timers say it was the worst year they can remember.

“We have been through some dry times. In 1954, when my dad and grandfather farmed here, they pretty much had nothing because it was so dry,” said Paul McCormick who farms with his son, Jack, in Ellis Grove, Illinois, south of St. Louis. “But I think this was a topper for me this year.”

Now, however, farmers are facing the prospect of not being able to sell their grain at all because they can’t get it to market. The farmers may also struggle to find other bulk items, such as fertilizer, that are typically shipped by barge.

“Most of the grain produced on our farm ends up bound for export,” said Jack McCormick, who raises beef cattle and grain with his father. “It ends up going down the river. That is a very good market for us, and if you can’t move it that means a lower price, or you have to figure out a different way to move it. It all ends up as a lower price for the farmers.”

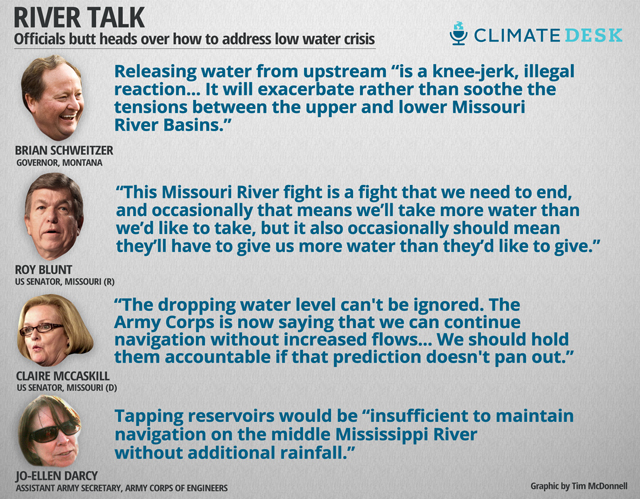

The shipping industry in St. Louis wants the White House to order the release of more water from the Missouri River, which flows into the Mississippi, to keep waters high enough for the long barges that float down the river to New Orleans.

Foster said the extra water would be for 60 days or so—time for the Army Corps of Engineers to blast and clear the series of rock pinnacles down river, near the town of Thebes, that threaten barges during this time of low water.

But sending out more water from the Missouri would doom states upstream, such as Montana, Nebraska, and South Dakota, which depend on water from the Missouri and are also caught in the drought.

“There are farmers and ranchers up there with livestock that don’t have water to stay alive. They don’t have enough fodder. They don’t have enough irrigation water,” said Robert Criss, a hydrologist at Washington University in St. Louis who has spent his career studying the Mississippi. “What a dumb way to use water during a drought.”

Elected officials from South Dakota and elsewhere have pushed back strenuously at the idea of sending their water downstream. Foster reckons there is at best a 50-50 chance Obama will agree to open the gates.

But such short-term measures ignore an even bigger problem. Climate scientists believe the Mississippi and other rivers are headed for an era of extremes, because of climate change.

This time last year, the Mississippi around St. Louis was 20 feet deeper because of heavy rain. In the spring of 2011, the Army Corps of Engineers blew up two miles of levees to save the town of Cairo, Illinois, and Missouri farmland, and deliberately flood parts of rural Louisiana to make sure Baton Rouge and New Orleans stayed dry.

“It has kind of switched on us, and it switched pretty quick,” said the Coast Guard chief Ryan Christiansen. “It wasn’t that long ago that you had pretty high flooding, and now we are heading towards record lows.”

Others argue that the Mississippi is already overengineered, after a century and a half of tampering with the river’s natural flow.

Over the decades, Congress funded a number of projects to deepen the shipping channel, doubling it in depth to nine feet, and building an elaborate system of locks and dams to keep the river in a confined space.

The Army Corps of Engineers is constantly dredging the river’s sandy bottom or building new levees to keep barges moving.

Those efforts to confine the river to a deep and narrow channel are believed to have made surrounding areas more vulnerable to extreme floods—like in 2011, when thousands were forced to flee their homes.

They may also not make sense in the long-term use of the river.

Criss argues the long barge trains floating on the Mississippi are just too big for the upper reaches of the river anyway, and that the industry is unfairly subsidized compared with other transport providers such as rail.

“The whole system around here has been entirely reconfigured to accommodate these monstrous barges,” he said.

“This is the whole problem. We want to run boats on the river with nine-foot drafts that are almost a quarter of a mile long. They are too big for the size of the river up here.”

The Mississippi, Criss said, needs smaller boats.

The Mississippi River has long been a flashpoint for climate change. Climate Desk has collected and mapped stories from our partners over the last several years; click on the map below to explore.