The anti-Keystone "Forward on Climate" rally in Washington DC, February 17th, 2013.Jay Mallin/ZUMA Press

On February 17, more than 40,000 climate change activists—many of them quite young—rallied in Washington, DC, to oppose the Keystone XL pipeline, which will transport dirty tar sands oil from Canada across the heartland. The scornful response from media centrists was predictable. Joe Nocera of the New York Times, for one, quickly went on the attack. In a column titled “How Not to Fix Climate Change,” he wrote that the strategy of activists “who have made the Keystone pipeline their line in the sand is utterly boneheaded.”

Nocera, who accepts the science of climate change, made a string of familiar arguments: The tar sands will be exploited anyway, the total climate contribution of the oil that would be transported by Keystone XL is minimal, and so on. Perhaps inspired by Nocera-style thinking, a group of 17 Democratic senators would later cast a symbolic vote in favor of the pipeline, signaling that opposing industrial projects is not the brand of environmentalism that they, at least, have in mind.

The Keystone activists, not surprisingly, were livid. Not only did they challenge Nocera’s facts, they utterly rejected his claims as to the efficacy of their strategy: Opponents of the pipeline have often argued that it is vital to push the limits of the possible—in particular, to put unrelenting pressure on President Obama to lead on climate change. Van Jones, the onetime Obama clean-energy adviser and a close supporter of 350.org founder and Keystone protest leader Bill McKibben, has put it like this: “I think activism works…The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender movement kept pushing on the question of marriage equality, and the president came out for marriage equality, which then had a positive effect on public opinion and helped that movement win at the ballot box and in a number of states, within months.”

This article is about the emotionally charged dispute between climate activists and environmental moderates, despite their common acceptance of the science of climate change. Why does this sort of rift exist on so many issues dividing the center from the left? And what can we actually say about which side is, you know, right?

Does Joe Nocera really have a sound basis for calling the pipeline opponents’ strategy boneheaded—or is that just his gut feeling as a centrist? Does Van Jones have any basis for claiming that activism works—or is it just his gut feeling as someone favorably disposed towards activism?

It’s high time we considered the science on these questions. There is, after all, considerable scholarly work on whether activists, by pushing the boundaries of what seems acceptable, create the conditions for progress or, instead, bring about backlashes that can complicate the jobs of sympathetic policymakers.

There’s also data that may shed light on why these rifts between “moderates” and “activists” are more the rule than the exception—across the ideological spectrum. “I can’t really think of any movement where there isn’t some internal dissent about goals and tactics,” says Carleton College political scientist Devashree Gupta, who studies social movements. The recurrence of this pattern on issues from civil rights to gun control to abortion suggests that there is something here that’s well worth understanding, preferably before the next rhetorical bloodbath around Keystone.

A chief benefit of this line of inquiry: It should prove duly humbling to activists and moderates alike—and thus might help to unite them.

FROM THE OUTSET, I think we can agree on one fundamental point: Over the past several years, driven by the failure of cap and trade and a worsening climate crisis, America’s environmental movement has become considerably more activist in nature—some might even say “radical.” Exhibit A is the successful attempt by 350.org inspirer-in-chief McKibben (who has written extensively about climate for Mother Jones) to create a grassroots protest movement rather than simply to work within the corridors of power.

“What Bill is doing is actually quite impressive—he’s the first one to create a social movement around climate change, and he’s done it by creating a common enemy, the oil industry, and a salient target, which is Keystone,” says Andrew Hoffman, a professor at the University of Michigan who studies environmental politics.

One crucial aspect of this shift is a growing reluctance by environmentalists to work hand in hand with big polluters. The latter was a central feature of the US Climate Action Partnership, the industry-environmental collaboration that led an unsuccessful cap-and-trade push a few years back. Nowadays, the environmental movement is moving toward a more oppositional relationship with industry, as evidenced by its attempts to block a major industrial project (Keystone) and to get universities and cities to drop their investments in fossil fuel companies (another of McKibben’s goals).

The rival environmental factions are sometimes described as “dark greens” (the purists who want to force radical change) and “bright greens” (those who seek compromise and accept tradeoffs). There’s really little doubt that dark greens are on the ascendant. “He’s pulling the flank out,” Hoffman says of McKibben. “I do think he has a valuable role in creating a space where others can create a more moderate role.”

It’s also fair to say that McKibben—the charismatic journalist-turned-organizer—lies a good way to the political left. Its centrist biases notwithstanding, a recent paper by American University communications professor Matthew Nisbet does capture McKibben’s “romantic” ideology: Like most people, he’s unhappy about environmental degradation, but he also seems opposed, in a significant sense, to the economic growth engine that drives it. He believes in living smaller, in going back to nature, in consuming less—not a position many politicians would be willing to espouse. (Indeed, President Obama’s comments about climate change often contain an explicit rejection of the idea that environmental and economic progress are mutually exclusive.)

So environmentalists are moving left and becoming more activist in response to political gridlock and scary planetary rumblings. Then along come the moderates, unleashing flurries of what Grist‘s David Roberts calls “hippie punching” under the guise of being more rational and reasoned than those they are criticizing. For example, Nisbet writes: “McKibben’s line-in-the-sand opposition to the Keystone XL oil pipeline, his skepticism of technology, and his romantic vision of a future consisting of small-scale, agrarian communities reflects his own values and priorities, rather than a pragmatic set of choices designed to effectively and realistically address the problem of climate change.”

You can see how an activist might find this just a tad irritating. For what is Nisbet’s statement if not a reflection of his own values and priorities? Words like “pragmatic” and “realistic” give away the game.

THE TRUTH IS, ?there is every reason to suspect that both groups are driven by divergent emotions, passions, and personality dispositions—or at least, so says the body of research (admittedly, still in an early phase) that exists on the matter.

We live in an era in which politics seems less and less comprehensible without turning to psychology. In particular, there is a growing realization that today’s Democrats and Republicans simply don’t understand one another, and are trapped in a kind of unending political Mars and Venus saga due to their divergent personalities, psychologies, and emotionally rooted moral systems.

Yet anyone who has hung around the environmental movement long enough may have noticed an eerily similar version of this phenomenon in the divide between moderates and activists. And there are at least some researchers out there helping us to make sense of this divide.

First, let’s consider the personalities of so-called moderates: Research by Yale political scientist Alan Gerber and his colleagues suggests that people who score high on the personality trait “openness to experience” are not only more likely to lean liberal (a long-standing finding in political psychology) but, more surprisingly, are more likely to insist on remaining politically unaffiliated—in which case they tend to identify themselves as centrist, moderate, or independent.

It appears that openness to experience, beyond its literal meaning, signals a desire to stand out from the crowd. These people are not joiners, or team players. So it would not be out of character for them to criticize people on their side of the aisle in order to distinguish themselves from their presumed allies. In this camp, we might expect to see plenty of instinctive contrarians, like the pundits and journalists who enjoy declaring a pox on both houses.

So, are moderates like Nocera really more rational or reasonable than activists? Gerber’s results suggest that there may simply be a “moderate” personality for whom this contrarian hippie-punching instinct simply feels right.

Beyond the personality studies, there is a growing body of research on the deep-seated emotions that underlie our personal politics. Dubbed “moral foundations theory,” it consists largely of work done by New York University psychologist Jonathan Haidt, Jesse Graham of the University of Southern California, and their colleagues and collaborators. Their approach is to measure the five (sometimes six) moral “foundations” that seem to drive our responses. (They are: “care/harm,” “fairness/cheating,” “loyalty/betrayal,” “authority/subversion,” and “sanctity/degradation.”) In short, they have been able to demonstrate that people’s views on right and wrong, and the intensity with which we respond to moral and political situations, have more to do with our gut instincts than rational consideration of the facts before us; our moral “reasoning” is actually a form of post hoc rationalization.

What can moral-foundations theory tell us about the chasm between environmental moderates and activists? Ravi Iyer of USC, a collaborator of Haidt and Graham, agreed to run some data for me, based on a sample of 15,552 individuals who responded to the researchers’ moral-foundations questionnaire, as well as a separate questionnaire that included a question about environmental attitudes.

The result was revealing: People who had professed that it is important to “protect the environment” not only tended to be liberal (no surprise), but they also exhibited a considerably higher sensitivity to moral considerations about “care/harm.” In other words, when they weighed the right and wrong of a given situation, these respondents were more concerned than their fellow citizens about “whether or not someone suffered emotionally” and “whether or not someone cared for someone weak or vulnerable.”

Iyer suggests that environmentalists’ care/harm considerations extend far beyond the immediate and the local—they also apply to distant peoples, animals, habitats, and future generations. (This finding is consistent with a recent study on the “moral roots” of environmentalism by Matthew Feinberg of Stanford and Robb Willer of the University of California-Berkeley.)

Iyer then ran a second analysis. He compared the moral responses of liberals who scored highest in their desire to protect the environment with those of liberals who scored lower, yet still said they cared about the environment. This analysis, a proxy for the differences between the environmental purists and moderates, turned up relatively small but still noteworthy differences. The purists, or activists, tended to be more sensitive to three of the five moral foundations: “care/harm,” “fairness/cheating,” and “sanctity/degradation.” This suggests that if you want to engage an environmentalist activist on an emotional level, you should try a moralizing narrative: A corporation with too much power (unfair) is causing devastating damage (care/harm), defiling (sanctity/degradation) the environment and jeopardizing the planet for future generations (care/harm). Sound familiar?

Perhaps most revealing, though, was the center-vs.-left difference in the realm of “sanctity/degradation,” a moral sensibility associated with disgust that is usually much stronger on the political right than on the left. It is measured by asking people how much they factor in “whether or not someone violated standards of purity and decency” and “whether or not someone did something disgusting” when deciding what is moral or immoral. Iyer’s analysis suggests that environmental activists, more so than the moderates, associate the environment with purity and feel revulsion when it is defiled. This may leave them viscerally offended by perceived abuses of the sanctity of nature—and less willing to compromise on their ideals.

The moderates, who are less driven by pure “care/harm” concerns, may tend to be less emotional about preserving the environment in a pristine state, and are thus more willing to endorse trade-offs. “The more moderate you are, the less extreme you are in any of the moral foundational domains,” says Stanford’s Matthew Feinberg. “So you probably are more utilitarian or consequentialist in the way you perceive the world.”

Does this mean that moderates are more rational? Insofar as they are less moralistic, they have something of a claim. But it is offset by their tendency towards knee-jerk centrism, which can be just another reflex.

The bottom line is that the activists and moderates respond and feel differently when faced with the same moral and political situation. And both factions are likely biased by their initial, emotional responses. Thus, a moderate can be just as reactionary as an activist—especially if he or she never moves beyond that first instinct and simply splits the difference between the opposing sides in every situation.

LET US NOW return to the Keystone debate. If you’ll recall, the moderates’ instincts tell them that activists create backlash that interferes with the movement’s wider goals, whereas the activists believe their protests create space for, at minimum, the achievement of more moderate goals. So which side is correct?

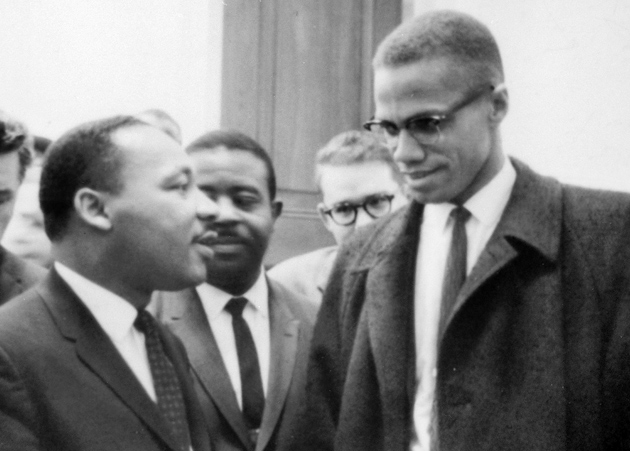

To answer that question, we have to turn to a different body of research: the study of “radical flank effects” in social movements. Perhaps the most seminal work on the matter was Black Radicals and the Civil Rights Mainstream, 1954-1970, a book published in 1988 by Herbert Haines, a scholar at the State University of New York-Cortland. Haines argued, provocatively, that radical groups like the Black Panthers and individuals like Malcolm X actually helped make space for a series of moderate successes (led by Martin Luther King Jr.) that culminated in the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Haines called this a “positive radical flank effect” because it led to a beneficial outcome for civil rights. But he also raised the possibility of “negative radical flank effects”—indeed, a delayed civil rights backlash had kicked in by the early 1970s. But overall, he argued, the presence of the radicals and their growing prominence helped create favorable conditions for the moderates to push important legislation.

The radical flank concept now “has a lot of credibility among social-movement scholars,” says Riley Dunlap, a sociologist at Oklahoma State University who studies climate change (and the people who claim it isn’t real). The concept has since been applied to political movements and moments ranging from women’s rights to the New Deal.

Some of Haines’ observations sound entirely relevant to today’s environmental moment. For instance: “Radicals specialize in generating crises which elites must deal with”—Keystone anyone?—”while moderates specialize in offering relatively unthreatening avenues of escape.” In other words, it’s a symbiotic relationship: The moderates are more attractive for the power brokers to negotiate with, Haines writes, “but all the more so when more militant activists are applying pressure.”

The sad irony here is that the activists don’t get what they want. In the end, they merely get to help out the moderates. But that’s the nature of the positive radical flank effect.

For this article, I asked several sociologists and specialists on movements—Haines included—how one might apply the radical flank theory to the current environmental movement. Short answer: It’s tough without the benefit of hindsight. “It’s easy to do when you look over the course of history, but when it’s right in the moment, it’s really complex,” explains Jules Boykoff, a specialist on social movements at Pacific University in Oregon.

First, it is important to acknowledge, as Haines did, that the definition of “radical” hinges entirely on what society considers mainstream—and that’s a moving target. The tactics of radicals vary greatly, too—in this context, the peaceful anti-Keystone movement hardly counts as extreme.

But certain scholarly considerations may prove illuminating. For instance, one of the critical factors in determining whether a radical flank effect will be positive or negative is the way moderates and activists relate to one another. “How clearly are the moderates and radicals differentiating themselves?” asks Carleton College’s Devashree Gupta. This, as Gupta notes, shapes media coverage and the thinking of politicians and policymakers who may be calculating whether helping the moderates will ease the headaches the radicals create for them.

It is noteworthy that as the Keystone XL pipeline protests have heated up, environmental organizations have not differentiated themselves clearly. Indeed, the leaders of typically moderate groups such as the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council wrote a letter to President Obama in 2011 noting that “there is not an inch of daylight between our policy position on the Keystone Pipeline and those of the very civil protesters being arrested daily outside the White House.”

A second major consideration involves policy momentum. Here, the question is whether all sides agree that change is coming anyway. If so, a positive radical flank effect is more likely, as the status quo comes to envelop and embrace moderates (and spurn radicals). “For a positive effect to happen,” Haines explains, “what you kind of have to have is things moving in the right direction politically. So around environmentalism, it would have to be that policy is already moving in a pro-environmentalist direction, like civil rights was, and the radicals come along and give it a boost.”

Are things moving that way? That’s incredibly difficult to discern at the moment. Climate progress is clearly in congressional limbo. But culturally, you could say that there is indeed momentum as the public awakens to the reality of increasingly extreme weather, and even the Wall Street Journal is publishing op-eds supporting a carbon tax. There is also positive momentum in the sense that Obama clearly wants to do something for his environmental legacy, and there is still much he can do without cooperation from Congress.

Finally, any radical-flank analysis must consider the possibility of backlash. In a sense, that backlash has already happened, as the political right has taken up Keystone XL as a case study in environmentalists wanting to kill jobs. Haines cautions: “If you’ve got a radical flank and a very polarized environment, where there’s no real concept or impulse to compromise on the other side, then not only is more-militant stuff less likely to encourage progress, but it can become a weapon that the other side uses.”

In other words, the jury is still out on whether the Keystone protests will encourage positive action on climate—so it’s awfully premature to be calling the strategy “boneheaded.” Mobilizing thousands of people, drawing massive media attention, perhaps redefining environmentalism—these are all actions that, even if they do produce some backlash, will assuredly have myriad other effects that are difficult to foresee.

But the protesters might also take a gut check from this analysis: Their success is far from certain. And most galling, from the vantage point of history, their “success” may well be defined by their failure on the specific issue they care most about. It is not hard to imagine, for instance, an outcome that would be the very definition of a positive radical flank effect: Obama approves Keystone and simultaneously announces a number of initiatives long desired by centrist environmental organizations. Chief among them: new steps by the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants.

The activists would be bitterly disappointed, of course, but progress would be real and tangible. In this context, would Van Jones be wrong in saying that “activism works”?

TO SUM THINGS UP, we’ve seen that there is likely a deep seated, emotional and dispositional reason why some people wind up as activists and others as moderates. Perhaps the rift between the Noceras and the McKibbens of the world will make more sense—and even, perhaps, be diminished—if we can all accept the fact that enviros on both sides of the Keystone protests are feeling their way to their opinions.

Second, the study of social movements suggests that both outcomes—progress and backlash—can occur simultaneously, and the activists might well win by losing (or, if you prefer, lose by winning). Given all of the complexities, calling the mobilization of thousands of people around climate action “boneheaded” is, well, just that.

In the final analysis, it’s hard not to admire what McKibben and his supporters have pulled off. We don’t yet know which way the radical flank effect will go, but until fairly recently, there wasn’t even a flank to discuss. “The reality is that we’ve had no radicals so far, until Bill McKibben,” says Oklahoma State’s Riley Dunlap. McKibben has thrown the switch, and now the gears are turning, to uncertain end.

As we wait for the outcome, there’s a lesson here for the moderates: Un-jerk those knees. For moderates’ actions matter, too, and their choices may have historic consequences. “Whether it’s a positive or negative flank effect, we decide that,” says Jules Boykoff. “If you diss somebody, dismiss them, use them for your short term gain, you might sacrifice that group on the altar of missing what you actually want to happen.”

If the “bright greens” want to be known for nuanced views, sophistication, and willingness to endorse complexity and tradeoffs, then let them begin with this simple acknowledgement: Determining the historical impact of a movement like this one is anything but simple.