<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/scjody/495643172/sizes/z/in/photolist-KNirW-pLrLR-KNtRx-b7j3v-b7j5z-b7iF4-b7iLP-b7iTC-b7jde-b7iXr-b7jgU-b7iZQ-b7j9o-9MAroH-2E13XA-2DZZSy-2DVZJv-2E3eJK-5zBjp7-5zBiAC-5zBjZW-89xGYk-8E715f-7QPMTV-pLrLT-pLrLW-7HAPe-5zx2Ha/">scjody</a>/Flickr

This story first appeared on the Atlantic Cities website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Today marks the 10th anniversary of the Northeast blackout of 2003, the largest power outage in North American history.

For a while, this colossal disaster was a shared reference point for millions. We salvaged a tub of ice cream on the roof, hitched a ride home with strangers, directed traffic at a darkened intersection, and so on. Everyone had a story.

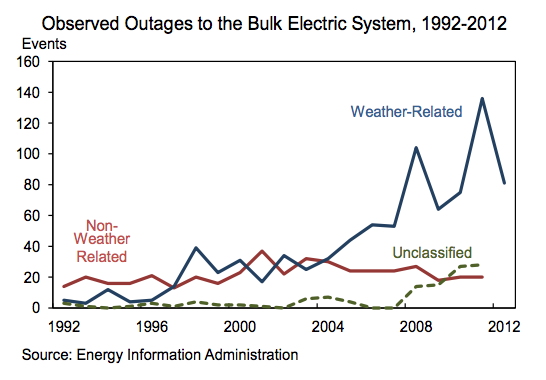

But a decade later, it seems a faded memory. For those in the affected area, recollections have been supplanted by disaster stories of Superstorm Sandy, and then some. Despite regulations tightened in response to the 2003 blackout, power outages – particularly those caused by the weather – are more common than ever.

According to a new report released by the Department of Energy this month [PDF], there were 679 widespread (affecting at least 50,000 people) power outages due to severe weather between 2003 and 2012. The cost of these incidents has been calculated to be anywhere between $18 and $70 billion per year.

There are two explanations for this spike. First, the grid is getting older. Second, the weather is getting (or at least has gotten, in the last ten years) worse.

What’s changed since 2003, from an infrastructure standpoint? The National Energy Policy Act, passed in 2005, has successfully compartmentalized grid malfunctions. This reduces the chance of another “domino effect” like the one that took place a decade ago, when a glitch in an Ohio alarm system shut down the power for 55 million people. The Recovery Act of 2009 set aside $4.5 billion for technology improvements, like sensors, to improve the grid’s resilience. Other achievements include the requirement that power companies trim trees around lines, and a bevy of other, more technical regulations.

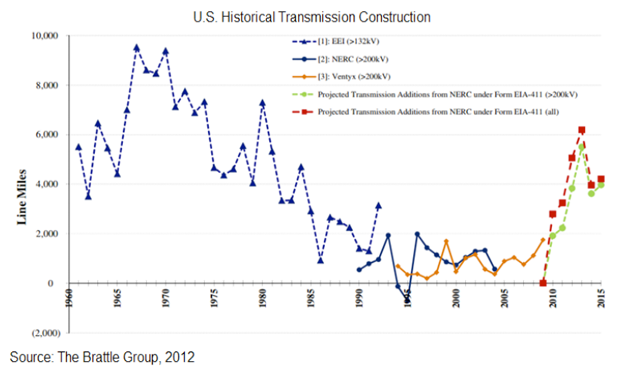

And yet, despite a burst of construction of transmission lines in the past five years, the grid is aging faster than we can rebuild it. We haven’t approached the rates of line construction that characterized the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Seventy percent of transmission lines and transformers, according to the report, are now over a quarter-century old.

Particularly where extreme weather adaptations are concerned, power companies have (evidently) failed to keep up. Even if another enormous regional blackout is unlikely, low-lying transformers and aerial power lines leave grid-dependent population centers vulnerable. The financial case for resilience—spending now to save later—has not yet sunk in.

What has changed since 2003, however, is the level of readiness at the municipal level. Natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Ike have inspired coastal cities to revise disaster preparations. Counter-terrorism funding distributed to big cities since 9/11 has been used to develop sophisticated and versatile emergency response plans. And when bad weather bears down, cities have adopted a “better safe than sorry” approach, shutting down basic services as a cautionary measure.

When the power goes out next time, your city may be ready, even if your energy company wasn’t.