<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:121030-F-AL508-159_Aerial_views_during_an_Army_search_and_rescue_mission_show_damage_from_Hurricane_Sandy_to_the_New_Jersey_coast,_Oct._30,_2012.jpg">US Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Mark C. Olsen</a>/Wikipedia

This story first appeared on the Atlantic Cities website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the history of the United States, we’ve moved people for all sorts of reasons, blithely certain that they’ll be fine. The sterile terms we’ve given these processes—”managed retreat” or “urban renewal”—suggest that they’re, well, manageable. But it’s not as easy as the planners would have us believe. Over decades, I have studied the significant social, emotional, and psychological costs of displacement. As a psychiatrist, I have seen the painful and often unseen effects of urban renewal, gentrification, and other major changes in cities.

Displacement triggers lifelong sorrow, what psychologist Marc Fried famously called “grieving for a long home.” And it’s not just grief over a place. Displacement breaks up social networks, and disperses social capital. It costs individuals an enormous amount of money, very little of which is replaced by any of the “repayment” schemes, which typically cover the cost of a house, but not the intangibles like replacing one’s neighborhood. And it sets people back, adding opportunity costs to other kinds of problems. I’ve called this “root shock,” to try to capture the ways in which upheaval disturbs our very connection with the earth.

Experts tend to use displacement to mean moving people away from a particular geography. But recent storms in New Jersey, where I live, have caused me to reconsider this definition. In August 2011, Tropical Storm Irene was supposed to bear in on the coast of New Jersey, so my family and I decided to wait out the storm in the New York town of Warwick. As fate would have it, the storm hit there directly, flooding the downtown and nearby roads. On arriving home, I found two feet of water in my basement. Then, in October 2011, a freak snowstorm swept through the region before leaves had fallen from the trees, breaking limbs, downing electric lines and flooding my basement. Halloween was canceled. Just one year later, in October 2012, Hurricane Sandy destroyed our train service into New York City, where I work. It was months before the route was fully restored. To cap it all off, a nor’easter ripped through the region the following February, causing yet more damage.

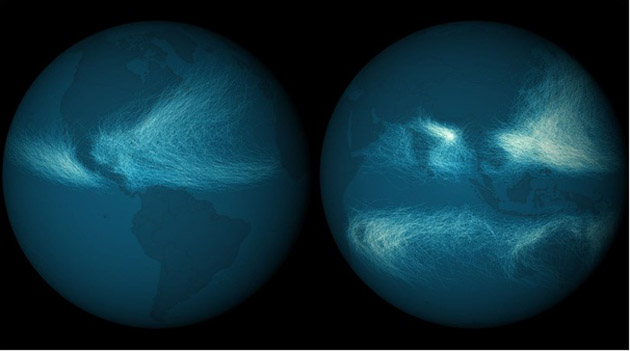

While many people living in the Sandy-affected region have been physically displaced by the storm, all of us—even those who continue to live in the same location—have to reconcile the fact that we now live in a new weather system. While the weather displaced some of us from our homes, it cost us all a way of life. This is a different, but very profound, kind of displacement.

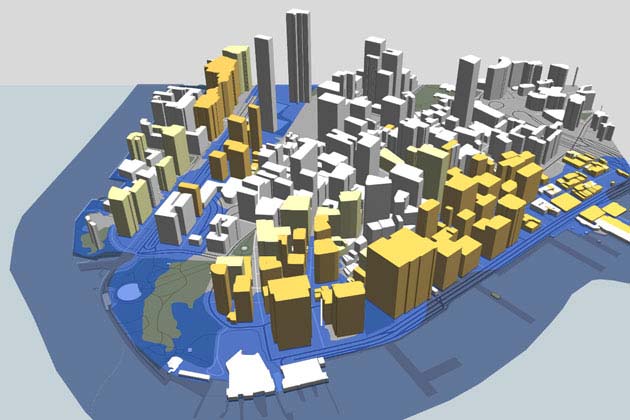

It is with this mindset I look at the reality we now inhabit. Sandy led FEMA to change its flood maps, which means countless homeowners now face a steep rise in insurance costs. That will lead some people to move, undermining communities and the very nature of the shore, which, in many ways, holds New Jersey together.

Understanding displacement isn’t just a matter of determining who lives in the FEMA flood zone and who lives safely outside it. Homeowners like me, five miles from the water’s edge, depend entirely on trains, gas deliveries and electricity, and all of this regional infrastructure is situated at the water’s edge. Flooding in my basement threatens all the equipment that makes my house function – my furnace, hot water heater, washer and dryer. I have put in a sump pump, but now I need a generator to run it if the electricity fails. I am saving up for the generator, and hoping I get the money before we get a storm. That is only the beginning of the costs I face in refitting my house for the new weather.

As an adviser to Rebuild by Design, I have helped teams develop their plans for Hurricane Sandy recovery. As the designers tackle the implications of their research, it is important to remember that climate change has deeply personal effects. I’ve asked designers to consider the Jersey Shore, for example, as the center of New Jersey, a place that is held together by homeowners now facing high insurance. By living on the shore, those homeowners help maintain one of the state’s greatest assets — might we plan differently if we understood that they are the backbone of New Jersey’s tourism industry?

We want to come through this crisis a stronger region. But to do that we must take good care of everyone who is displaced. In this situation, that is everyone.