Photoilustration by Matt Connolly

The paleo diet is hot. Those who follow it are attempting, they say, to mimic our ancient ancestors—minus the animal-skin fashions and the total lack of technology, of course. The adherents eschew what they believe comes from modern agriculture (wheat, dairy, legumes, for instance) and rely instead on meals full of meat, nuts, and vegetables—foods they claim are closer to what hunter-gatherers ate.

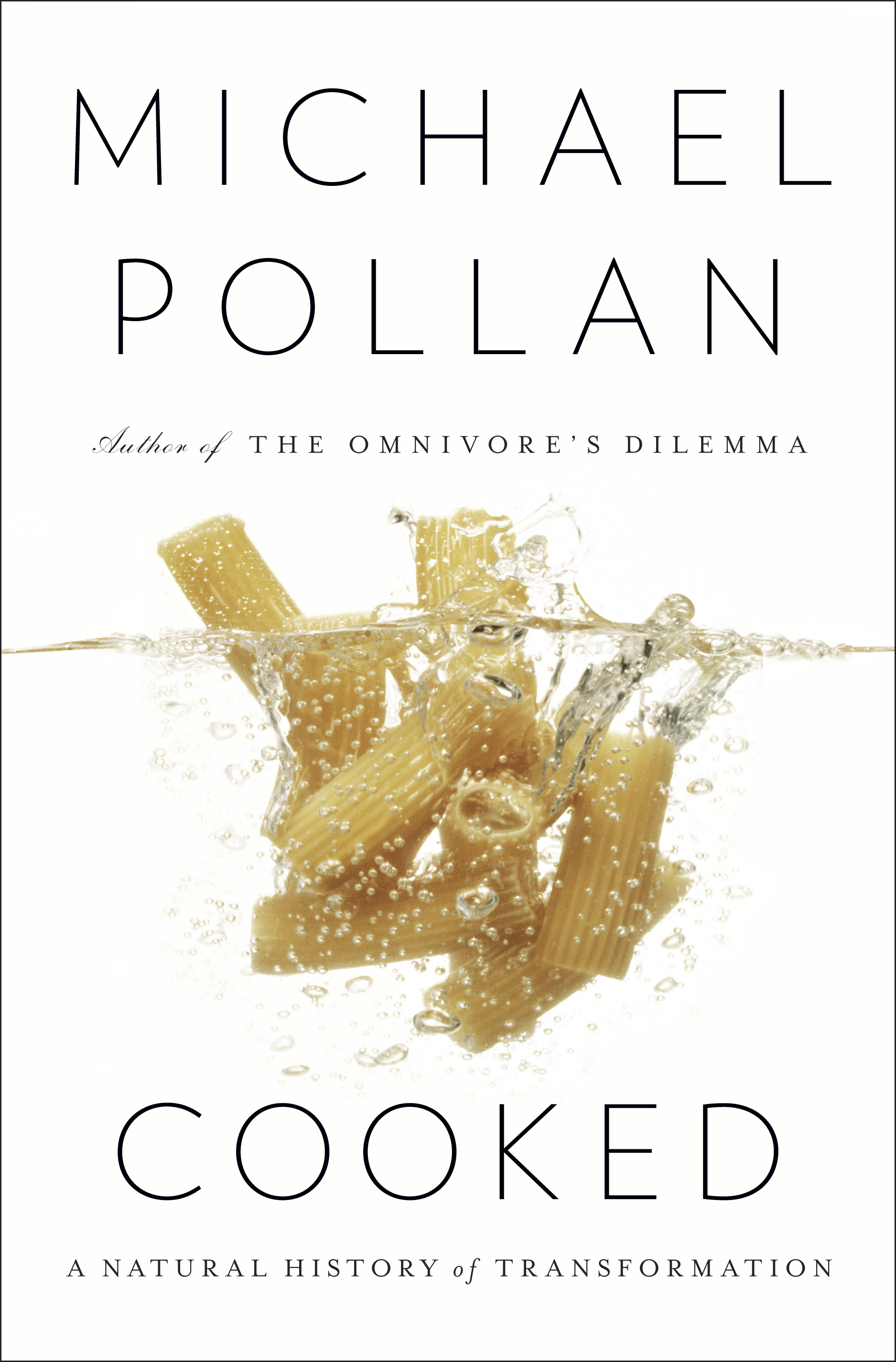

The trouble with that view, however, is that what they’re eating is probably nothing like the diet of hunter-gatherers, says Michael Pollan, author of a number of best-selling books on food and agriculture, including Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. “I don’t think we really understand…well the proportions in the ancient diet,” argues Pollan on the latest episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast (stream below). “Most people who tell you with great confidence that this is what our ancestors ate—I think they’re kind of blowing smoke.”

The wide-ranging interview with Pollan covered the science and history of cooking, the importance of microbes—tiny organisms such as bacteria—in our diet, and surprising new research on the intelligence of plants. Here are five suggestions he offered about cooking and eating well.

1. Meat: It’s not always for dinner. Cooking meat transforms it: Roasting it or braising it for hours in liquid unlocks complex smells and flavors that are hard to resist. In addition to converting it into something we crave, intense heat also breaks down the meat into nutrients that we can more easily access. Our ancient ancestors likely loved the smell of meat on an open fire as much as we do.

But human populations in different regions of the world ate a variety of diets. Some ate more; some ate less. They likely ate meat only when they could get it, and then they gorged. Richard Wrangham, author of Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, says diets from around the world ranged greatly in the percentage of calories from meat. It’s not cooked meat that made us human, he says, but rather cooked food.

In any case, says Pollan, today’s meat is nothing like that of the hunter-gatherer.

One problem with the paleo diet is that “they’re assuming that the options available to our caveman ancestors are still there,” he argues. But “unless you’re willing to hunt your food, they’re not.”

As Pollan explains, the animals bred by modern agriculture—which are fed artificial diets of corn and grains, and beefed up with hormones and antibiotics—have nutritional profiles far from wild game.

Pastured animals, raised on diets of grass and grubs, are closer to their wild relatives; even these, however, are nothing like the lean animals our ancestors ate.

So, basically, enjoy meat in moderation, and choose pastured meat if possible.

2. Humans can live on bread alone. Paleo obsessives might shun bread, but bread, as it has been traditionally made, is a healthy way to access a wide array of nutrients from grains.

In Cooked, Pollan describes how bread might have been first created: Thousands of years ago, someone probably in ancient Egypt discovered a bubbling mash of grains and water, the microbes busily fermenting what would become dough. And unbeknownst to those ancient Egyptians, the fluffy, delicious new substance had been transformed by those microbes. Suddenly the grains provided even more bang for the bite.

As University of California-Davis food chemist Bruce German told Pollan in an interview, “You could not survive on wheat flour. But you can survive on bread.” Microbes start to digest the grains, breaking them down in ways that free up more of the healthful parts. If bread is compared to another method of cooking flour—basically making it into porridge—”bread is dramatically more nutritious,” says Pollan.

Still, common bread made from white flour and commercial yeast doesn’t have the same nutritional content as the slowly fermented and healthier sourdough bread you might find at a local baker. Overall, though, bread can certainly be part of a nutritious diet. (At least, for those who don’t suffer from celiac disease.)

3. Eat more microbes. Microbes play a key role not just in bread, but in all sorts of fermented foods: beer, cheese, yogurt, kimchi, miso, sauerkraut, pickles. Thousands—even hundreds—of years ago, before electricity made refrigeration widely available, fermentation was one of the best means of preserving foods.

And now we know that microbes, such as those in our gut, play a key role in our health, as well. The microbes we eat in foods like pickles may not take up a permanent home in our innards; rather, they seem to be more akin to transient visitors, says Pollan. Still, “fermented foods provide a lot of compounds that gut microbes like,” and he says he makes sure to eat some fermented vegetables every day.

4. Raw food is for the birds (too much of it, anyway). There’s paleo, and then there’s the raw diet. Folks who eat raw tout the health benefits of the approach, saying that they’re accessing the full, complete nutrients available because they’re not heating, and thus destroying, their dinner. But that’s simply wrong. We cook to get our hands on more nutrients, not fewer. According to Wrangham, the one thing absolutely all cultures have in common is that they cook their food. He points out that women who move towards 100 percent raw diets often stop ovulating, because even if in theory they’re tossing sufficient food into the blender to fulfill their caloric needs, they simply can’t absorb enough from the uncooked food.

Our hefty cousins, the apes, spend half their waking hours gnawing on raw sustenance, about six hours per day. In contrast, we spend only one hour. “So in a sense, cooking opens up this space for other activities,” says Pollan. “It’s very hard to have culture, it’s very hard to have science, it’s very hard to have all the things we count as important parts of civilization if you’re spending half of all your waking hours chewing.” Cooked food: It gave us civilization.

5. Want to be healthy? Cook. Pollan says the food industry has done a great job of convincing eaters that corporations can cook better than we can. The problem is, it’s not true. And the food that others cook is nearly always less healthful than that which we cook ourselves.

“Part of the problem is that we’ve been isolated as cooks for too long,” says Pollan. “I found that to the extent you can make cooking itself a social experience, it can be a lot more fun.”

But how can we convince folks to give it a try? “I think we have to lead with pleasure,” he says. Aside from the many health benefits, cooking is also “one of the most interesting things humans know how to do and have done for a very long time. And we get that, or we wouldn’t be watching so much cooking on TV. There is something fascinating about it. But it’s even more fascinating when you do it yourself.”

For the full interview, in which Pollan also discusses cheese made from his belly button microbes and the latest research on how plants can hear insects snacking on neighboring leaves, listen here:

This episode of Inquiring Minds, a podcast hosted by best-selling author Chris Mooney and neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas, is guest-hosted by Cynthia Graber. It also features a discussion of the new popular physics book Trespassing on Einstein’s Lawn, by Amanda Gefter, and new research suggesting that the purpose of sleep is to clean cellular waste substances out of your brain.

To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. We are also available on Swell. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also recently singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” shows on iTunes—you can learn more here.

Photoilustration: Caveman: ollyy/Shutterstock; Scale: Fabio Freitas e Silva/Shutterstock; Kabob food: Africa Studio/Shutterstock.