Shutterstock

Most writings on climate are tedious or polemical. Windfall, journalist McKenzie Funk‘s fabulous new book on the business of climate change, is neither. Funk’s reporting takes him all over the globe. We meet investors who are buying up land in Africa and water rights in Australia and the American West, and are wagering hundreds of millions of dollars that climate-related drought and food shortages will earn them a fortune.

Funk visits Greenland secessionists who imagine the mineral wealth made accessible by a thawing tundra will bankroll their cause, as well as Israeli snow makers, Dutch seawall developers, geoengineering patent trolls, private firefighters, Big Oil scenario planners, and the scientists deploying mutant mosquitoes against dengue fever—a horrific tropical disease that’s crept into Florida of late.

In one particularly surreal chapter, he finds himself in Senegal meeting with African military officials overseeing the first phase of a quixotic 4,700-mile-long foliage barrier against the encroaching Sahara. In short, rather than waste our time on a settled question (duh, it’s real!), Funk offers an up-close-and-personal glimpse of climate change’s potential winners—and inevitable losers. The book is as fascinating and readable as it is unsettling.

In the excerpt below, a greatly trimmed version of Funk’s chapter “Uphill to Money,” we meet a fund manager for whom the recent predictions of severe drought in the West can only be good for business. After that, we’ll circle back for a chat with the author.

****

The following was published by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company. Copyright McKenzie Funk, 2014.

****

Where water Runs when it runs out

The offices of the world’s first water-focused hedge fund overlook a parking lot in a subdivided landscape developers call the Golden Triangle. The neighborhood gets its water from the Alvarado Water Treatment Plant, run by San Diego’s Public Utilities Department, which gets its water from the San Diego County Water Authority, which gets its water from the larger Los Angeles–dominated Metropolitan Water District, which gets much of its water—in greater proportions during California’s droughts—from the 242-mile Colorado River Aqueduct, which gets its water from a reservoir straddling the Arizona border, Lake Havasu, which gets its water from the 1,400-mile Colorado River, which gets its dwindling water from thousands of streams, snowfields, lakes, and springs in a drainage basin covering nearly 250,000 square miles across seven western states. Without imported water, the 2.7-million-person San Diego metropolis, like much of Southern California, would be no more capable of supporting people than the coastal desert it once was. During my visit, at the height of a hot summer in 2010, I got my water one morning from a secretary, who handed me a tiny plastic bottle—Poland Spring, was it?—from the fridge.

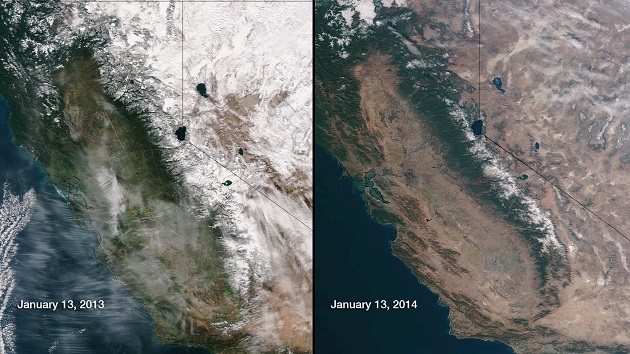

The man I’d come to meet was John Dickerson, the founder and CEO of Summit Global Management, a former CIA analyst, and the buyer of billions of gallons of water in two vital, desiccating river systems: the Colorado and Australia’s Murray-Darling. Both systems had recently experienced severe droughts that scientists tied to climate change. Financial managers like Dickerson, meanwhile, had experienced the opposite: a flood of money. Summit had launched its first water fund in 1999, but “for a long time,” he told me, “I was a voice in the wilderness. We couldn’t get anybody to buy our fund. Then came Al Gore and his stuff, the whole global-warming thing, droughts. Water became the go-to idea.”

For the climate investor, water was the obvious thing. Carbon emissions are invisible. But melting ice, empty reservoirs, and torrential rainstorms are tangible—the face of climate change. Water made it real. After An Inconvenient Truth, during 2007’s record melt in the Arctic, at least 15 water mutual funds launched globally; in two years, the amount of money under management ballooned tenfold to $13 billion. Credit Suisse, UBS, and Goldman Sachs hired water analysts, the latter calling water “the petroleum of the next century”—”At the risk of being alarmist,” Goldman said in a 2008 report, “we see parallels with Malthusian economics.”

Dickerson, in his late 60s, sat in a leather chair, and I sat across his desk from him. His bookshelf had three copies of An Inconvenient Truth and two of Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner’s seminal 1986 book on water and political power in the American West. “It’s the most necessary of all commodities,” Dickerson told me. “There’s no substitute for it at any price. And we cannot make water. Did you ever think about that, really? Hydrogen and oxygen. You can’t grow it.”

Already, global warming was creating shortages as the ratio of saltwater to freshwater increased. “The maldistribution of freshwater is getting much more severe,” Dickerson said. The supply/demand imbalance—fueled by population growth, accelerated by carbon emissions—was growing. It was a situation ripe for speculation, except there was no easy way for investors to get in. Summit’s first water fund, with $600 million under management, had navigated this roadblock by picking stocks within the $400 billion “hydrocommerce” sector—the business of storing, treating, and delivering water for use in households, manufacturing, and agriculture.

But Dickerson had decided that hydrocommerce wasn’t enough. He wanted actual “wet water”—the thing itself. In June 2008, he opened a second hedge fund, the Summit Water Development Group, to amass water rights in Australia and the American West. Already it had attracted hundreds of millions of dollars. “I’ve watched water rights go up and up,” he told me, lifting a hand into the air. “Just tick, tick, tick, tick.”

In the eastern United States, Dickerson explained, water could not be stripped from the land and sold as a separate commodity. The courts there followed English common law. “If you have 10 hectares of land, you get x liters from the Thames,” he said. “If you have 100 hectares, you get 10 times x from the Thames.”

The West was different. The Homestead Acts let pioneers win deeds to federal land if they lived on it for a period and made improvements. In dry years, common law could not stop farmers living upstream from using up all the water before it reached the others, since none of them owned the land. The law became essentially first come, first served. So long as the water was put to “beneficial use,” not hoarded, the oldest rights were the most valuable—and they could be freely traded.

Up and down the Colorado River system, Dickerson’s fund was buying stakes in private reservoirs, in ditches dug 150 years ago by pioneering ranchers—spending $500,000 here, $1 million there—whose water he hoped to package and sell to suburban boomtowns within the basin.

Since the dawn of the new millennium and the onset of the worst Colorado River drought in recent memory, country dwellers had migrated to cities and the rural-to-urban flow of water had doubled. There were now more people to eat food, and fewer to grow it, even as 18 of the 19 major scientific models predicted permanent drought in the Southwest by 2050, with conditions suggesting a new Dust Bowl in the making. The West’s fracking boom was putting new strains on the system; according to one study, energy companies controlled more than a quarter of the flow in the upper Colorado basin. In drought-plagued Texas, ranchers and cities already were being priced out of the water market by oil and gas interests. For the Summit Water Development Group, all of this was very good news.

As we said our goodbyes, Dickerson graciously loaded me up with books and reports. On top of the stack was Water for Sale: How Business and the Market Can Resolve the World’s Water Crisis, a 2005 book from the Koch brothers-funded Cato Institute. “Some people don’t like it,” my host conceded. “But this is what’s coming.”

****

Click here to read our interview with McKenzie Funk.