aijohn784/Thinkstock

Global warming isn’t just going to melt the Arctic and flood our cities—it’s also going to make Americans more likely to kill each other.

That’s the conclusion of a controversial new study that uses historic crime and temperature data to show that hotter weather leads to more murders, more rapes, more robberies, more assaults, and more property crimes.

“Looking at the past, we see a strong relationship between temperature and crime,” says study author Matthew Ranson, an economist with the policy consulting firm Abt Associates. “We think that is likely to continue in the future.”

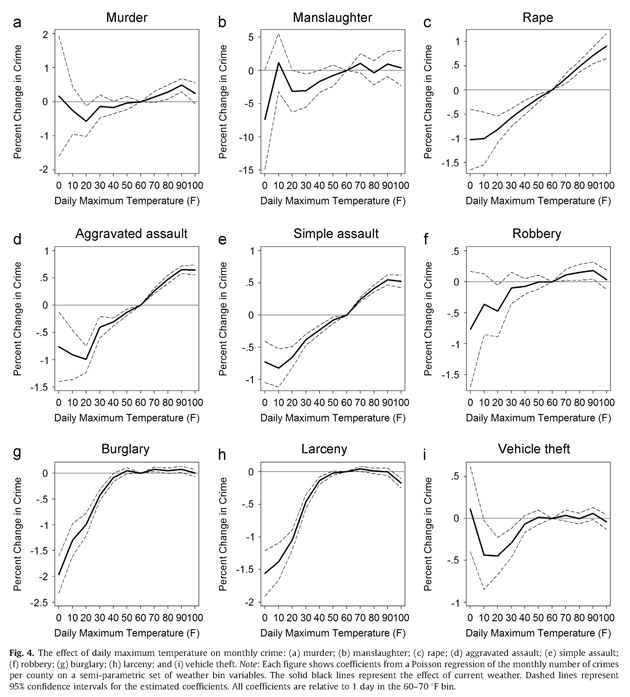

Just how much more crime can we expect? Using the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s warming projections, Ranson calculated that from 2010 to 2099, climate change will “cause” an additional “22,000 murders, 180,000 cases of rape, 1.2 million aggravated assaults, 2.3 million simple assaults, 260,000 robberies, 1.3 million burglaries, 2.2 million cases of larceny, and 580,000 cases of vehicle theft” in the United States.

Ranson acknowledges that those results represent a relatively small jump in the overall level of crime—a 2.2 percent increase in murder and a 3.1 percent increase in rape, for instance. Still, says John Roman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center, those numbers add up to “a lot of victims” over the course of the century.

The study’s results don’t mean that defendants should be able to argue that they were driven to a life of crime by the weather. “The decision to commit a crime is a matter of personal responsibility,” Ranson explained in an email. “Neither higher outdoor temperatures nor reduced police enforcement are valid excuses for individuals to commit criminal acts. Yet, from a statistical perspective, both cause crime to increase.”

So why would higher temperatures increase the crime rate? According to Ranson, the answer might vary depending on the type of crime. As shown in the charts below, property crimes, especially burglary and larceny, initially tend to increase as the weather warms but then level off once temperatures reach about 50 degrees. This suggests that cold weather may create obstacles to committing these types of crimes—Ranson cites closed windows, for example—obstacles that disappear when it’s warmer outside.

By contrast, the relationship between violent crime and temperature appears to be highly linear—as temperatures keep rising, so does the number of crimes. According to Ranson, this pattern supports the idea that “warmer temperatures increase the frequency of social interactions, some small percentage of which result in violence.” In other words, you’re more likely to mug someone if it’s warm enough to leave your house. But there’s another factor that Ranson suggests may also be playing a role: Past research indicates that as temperatures increase, people tend to become more aggressive.

Not every expert buys Ranson’s findings. Andrew Holland, a senior fellow for energy and climate at the American Security Project, says that the study seems “tailor-made for a headline” but that “on further analysis, I don’t know what it tells us.”

Holland sees climate change as a “threat multiplier” that could, in combination with other factors, exacerbate international instability and contribute to armed conflict. But he cautions against attributing individual events—be they armed robberies or civil wars—directly to climate change.

“Just like any war has many reasons for starting, any crime has many factors that go into it,” says Holland. “You can’t convince me that any one rape was solely because of the temperature.” Although attempting to separate out the various factors that contribute to a crime taking place can be “an interesting mathematical exercise,” Holland contends that it isn’t very “useful or helpful.”

But the Urban Institute’s Roman argues that the overall conclusion of Ranson’s study makes sense. Police have long operated with the understanding that “the summer is more dangerous than the winter,” explains Roman. “To the extent that climate change causes people to be out and interacting more, there will be more crime.”

Roman says the study can help policymakers begin to think about how to adapt their law enforcement practices to a warming world. “There will be more studies in the future that find these effects,” he says. “The concept fits with classic crime theory so neatly that we need to start thinking about how to get ahead of this and respond.”

Ranson has already thought about what that response might look like. One option is for communities to spend substantial amounts of money increasing the size of their police forces. Another possibility is that people will simply change their behavior in an attempt to avoid becoming the victims of crime—leaving their homes less frequently in nice weather or locking their windows.

Of course, there’s a third alternative—reining in the greenhouse gas emissions that are causing global warming in the first place.