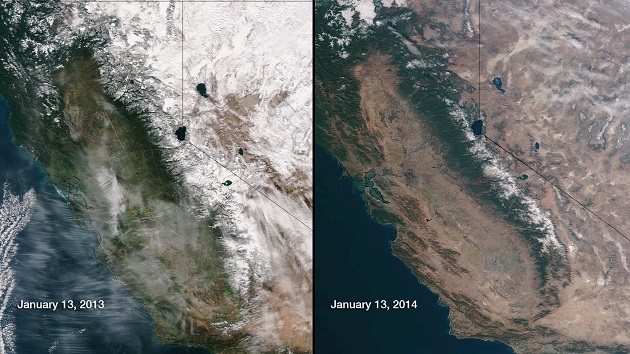

When people tell you to “eat your veggies,” they’re really urging you to take a swig of California water. The state churns out nearly half of all US-grown fruits, vegetables, and nuts; farms use 80 percent of its water. For decades, that arrangement worked out pretty well. Winter precipitation replenished the state’s aquifers and covered its mountains with snow that fed rivers and irrigation systems during the summer. But last winter, for the third year in a row, the rains didn’t come, likely making this the driest 30-month stretch in the state’s recorded history. So what does the drought mean for your plate? Here are a few points to keep in mind:

The abnormally wet period when California emerged as our fresh-produce powerhouse may be over. B. Lynn Ingram, a paleoclimatologist at the University of California-Berkeley and author of The West Without Water, says the 20th century was a rain-soaked anomaly compared to the region’s long-term history. If California reverts to its drier norm, farmers could expect an average of 15 percent less precipitation in the coming decades, and climate change could exacerbate that. Less rain means more irrigation water diverted from already dwindling rivers—bad news for river fish such as the threatened delta smelt. Wells won’t save the state, either: Farmers are already pumping the groundwater that lies deep under their farms much faster than it can be naturally recharged.

Cotton out, orchards in. California farmers have increasingly turned toward orchard crops like nuts, grapes, and stone fruit. That’s because those crops bring more return for the water invested than lower-value row crops like cotton, rice, and vegetables. But they also make for less flexibility: A broccoli farmer can let land lie fallow during a drought year, but an almond farmer has to keep those trees watered or lose a long-term investment.

California will keep getting nuttier. According to US Geological Survey hydrologist Michelle Sneed, there’s even been a push to convert unirrigated rangeland to permanent crops like almonds*. She says it’s not family farms driving this water-intensive push. Rather, it’s large finance firms like Prudential, TIAA-CREF, and Hancock Agricultural Investment Group. To cash in on surging demand for nuts among China’s growing middle class, these companies are buying up California farmland and plunking down nut orchards; acres devoted to pistachios jumped nearly 50 percent between 2006 and 2011, and the almond orchard area expanded 11 percent. Nuts are some of the thirstiest perennial crops around, with a single almond requiring a gallon of water and a pistachio taking three-quarters of a gallon. So when the finance companies snatch up farms in the Central Valley, they’re also grabbing groundwater—and California places no statewide limits on how landowners can exploit the water beneath their land. Even Texas, a state known for its deregulatory zeal, has stricter rules.

Mexico and China won’t fix this for us. Nearly half of the fruit and almost a quarter of the vegetables we eat come from abroad, mainly from Mexico, Canada, China, and Chile. But water supplies are dwindling worldwide. Mexico, for example, supplies 36 percent of our fruit and vegetable imports, almost all of it in the winter months. Most of that produce is grown in Sinaloa and Baja California, states that also are under intense water stress, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Parts of the Mediterranean have a California-like climate suitable for year-round farming, yet those places, too, have severe water issues (and an already-ravenous market for their goods in Europe). Even Southern Hemisphere countries like Chile, from which we get 8 percent of our imported produce, face serious water challenges.

But the Midwest could. According to a 2010 Iowa State University study, just 270,000 acres of land—about what you’d find in a single Iowa county, and a tiny fraction of the tens of millions of acres devoted to corn—could supply everyone in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin with half of their annual tomatoes, strawberries, apples, and onions, and a quarter of their kale, cucumbers, and lettuce. Add another 270,000 acres and the region’s farmers could grow enough for the parts of the country that aren’t as well suited for expanding fruit and veggie production, such as the Northeast, where land is too expensive and development pressures too high.

So why aren’t we seeding the heartland with lettuce already? The problem is that fruits and veggies would require a far different kind of infrastructure from the huge mechanical harvesters and grain bins used for corn and soy (most of which goes to feed livestock, not people). The transition would be pricey, and so far, few farmers have taken the chance. But the calculus could soon change: The US population will continue to grow, and, if current nutritional recommendations hold, so should our appetite for produce. This year, for example, a Harvard study found that after a 2012 change in federal school lunch standards, US students consumed 16 percent more vegetables. Eventually, California’s water issues will mean “large and lasting effects” on your supermarket bill, the US Department of Agriculture warned in February. Once the era of $7 a pound broccoli dawns, setting up the Midwest to grow fruits and veggies might not look so expensive after all.

*Correction: The original version of this article misstated hydrologist Michelle Sneed’s opinion about land use, making it sound like she thought finance firms were sucking up more water than family farms. As she responded to us in an email, “there is no evidence one way or the other! How could we know this since pumping is not measured/monitored?” We’ve amended the sentence in question, and regret the error.