Illustration by Chris Philpot

Illustration by Chris Philpot

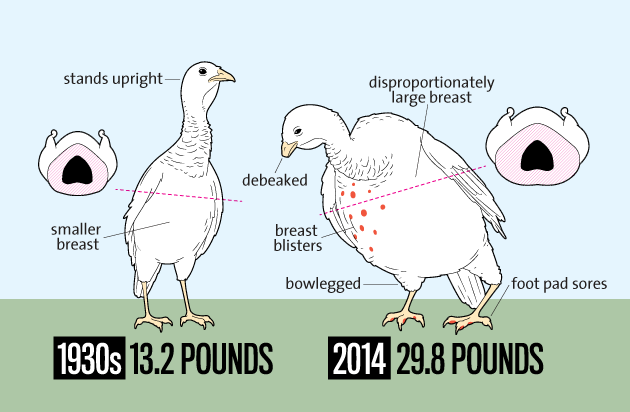

Thanksgiving turkeys are one of America’s oldest holiday traditions. But with their giant size, stooped frame, and limited mobility, today’s birds bear little resemblance to their early counterparts. So how did we end up with these modern megabirds? According to Suzanne McMillan, senior director of the farm animal welfare campaign of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, it wasn’t by accident.

Up until the the 1950s, turkeys found on Thanksgiving tables were essentially the same as their wild counterparts. But then, says McMillan, American poultry operations began to expand to meet Americans’ growing demand for meat. Turkey farmers began to selectively breed birds for both size and speed of growth—especially in the breast, the most popular cut among American diners. The birds grew so fast that their frames could not support their weight, and as a result, many turkeys were bowlegged and could no longer stand upright. The male turkeys, or toms, got so big—as heavy as 50 pounds—that they could no longer manage to transfer semen to hens. Today, reproduction happens almost exclusively through artificial insemination.

At around the same time, producers also began moving their operations indoors, where they could fit more birds and ensure that they developed uniformly, so turkeys’ feeding and care did not have to be individualized. In these close quarters, birds began to develop infections, like sores on their breasts and foot pads. To prevent these problems, and also to encourage growth, producers added low doses of antibiotics to the birds’ feed. Also because of space limitations, birds became aggressive and often resorted to cannibalism. In response, hatcheries began trimming birds’ beaks—known as debeaking—when they were a few days old.

If all of this makes turkey sound unappetizing, consider the latest development: As of October 20, turkey slaughter facilities were allowed to speed up their lines from 51 to 55 birds per minute—while also reducing the number of federal inspectors, as my colleague Tom Philpott has reported.

Consumer demand for cheap turkey has fueled these trends. The National Turkey Federation reports that turkey consumption has doubled over the last 30 years—today, the average American eats 16 pounds of turkey per year. Meanwhile, turkey prices haven’t increased much; in fact, this year turkey is cheaper than last year. Reuters reported that some grocery chains “use turkeys as ‘loss leaders’ to entice shoppers to buy other popular Thanksgiving foods.”

No wonder, then, that we end up trashing a lot of turkey:

By Jaeah Lee

By Jaeah LeeIf you don’t want to support turkey factory farms, McMillan says, look for birds that are certified through animal welfare programs. Grist has a good guide to picking a turkey with real humane bona fides here. A word of caution, though: This year, turkey giant Butterball says it has gone humane, but as Philpott reports, it so far hasn’t ditched many of the most cruel practices.