Flood waters from the Rock River surround homes in Barstow, Illinois, in April 2013.evin E. Schmidt/Quad-City Times/Quad-City Times/Zuma Press

The Midwest is no stranger to devastating floods. Last summer, the region was inundated with two month’s worth of rainfall in just one week, submerging farms and killing crops. Torrential downpours following a drought in Illinois in 2013 led to flooding that cost $1 billion. And Midwest flooding in 2008 caused 24 deaths and $15 billion in losses. Across the country, the United States has suffered from more than $260 billion in flood-related damages between 1980 and 2013—it’s the most common natural disaster experienced by Americans, according to FEMA.

Expect more of that in a climate-changed world. That’s the message from new research released Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Scientists have found that flood events in the Midwest have increased in number over the last 50 years. The researchers from the University of Iowa, funded by the National Science Foundation, studied 774 stream gauges across 14 US states and found that rivers over much of the region have burst their banks more often, resulting in more flooding.

According to the study, 34 percent of these gauges showed an increase in flooding events from 1962 to 2011, while only 9 percent showed a decrease. “The thing that I was surprised about the most was that there was such a coherent change” across the whole region, said one of the study’s authors, Gabriele Villarini, a hydrologist and engineer at the University of Iowa. Villarni described it as “a very homogeneous pattern.” That gave researchers confidence that the increase was the result of something more than simply localized weather or changes in specific watersheds, Villarini said. It was about bigger changes in the climate. There was “a nice, coherent pattern between rainfall and discharge” of rivers, he said.

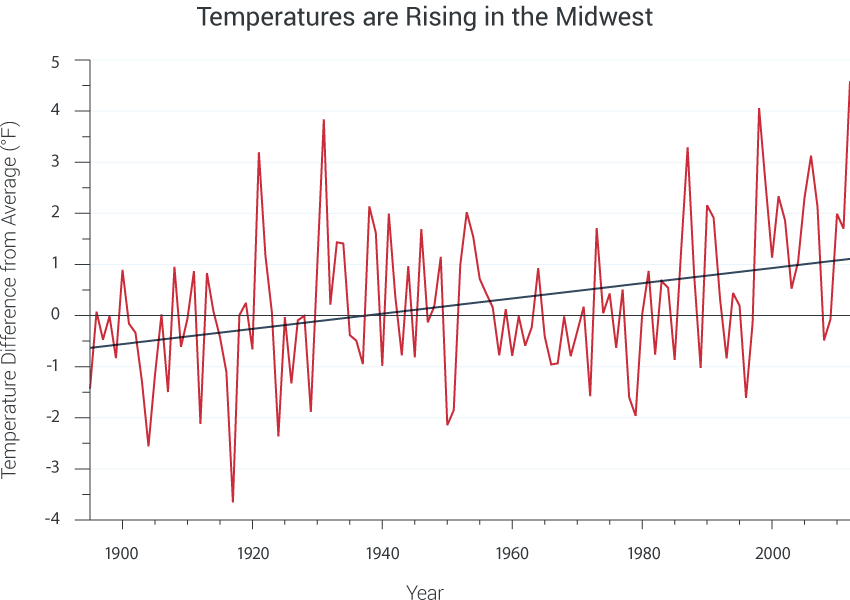

While the study does not attempt to pinpoint precisely how climate change might be directly responsible for these increased flooding events, the scientists say in the report that the changes “can be largely attributed” to changes in rainfall and temperature, with shifts in land surface temperatures “potentially amplifying this signal.”

That means the study’s findings are generally consistent with how climate scientists describe one of the major impacts of global warming: As the atmosphere warms, it can hold more moisture, resulting in more frequent episodes of intense precipitation, and therefore flooding. Last year’s National Climate Assessment reported that annual precipitation has increased over the past century, by up to 20 percent in some parts of the Midwest, in part “driven by intensification of the heaviest rainfalls.” That trend is likely to worsen.

In an earlier national assessment conducted by FEMA, the government found that rising seas and more severe storms are expected to increase the areas of the United States at risk of floods by up to 45 percent by 2100. These changes could double the number of flood-prone properties covered by the National Flood Insurance Program and drastically increase the costs of floods, the report found.

Quantifying the economic losses in the Midwest is the next step for the University of Iowa scientists: “Over the next several months we’ll be working on modeling the economic damages with these flood events,” Villarini said, to get a more accurate picture of the devastation, and to help local governments prepare answer the question: “How do we move forward in a world when we have to make decisions today, for structures and projects designed for the next 50 years?”

The research comes at the same that time the White House is pushing new rules for America’s flood-prone buildings, which put climate science at the center of federal regulations. At the end of last month, President Obama issued an executive order to implement a new “Federal Flood Risk Management Standard,” designed to reduce risks and cut the costs of future flood disasters. But the president’s plan is being met by Republican opposition—mainly from senators whose states border the Gulf of Mexico. These lawmakers question the legality of the executive order and imply that the White House didn’t do enough to solicit input before drafting the order.