Ruaridh Stewart/Zuma

There’s been a lot of talk lately about the drought in California, especially since this past week, when Gov. Jerry Brown introduced mandatory water cuts for the first time in the state’s history. So what exactly makes this drought so bad? And what are people doing about it? Here are a few important points to keep in mind:

Drought is the norm in California. How bad is this one? There are always wet years and dry years, but the past three years have been among the driest on record—and state officials worry that 2015 will be even drier. Last week, for the first time in the state’s history, Brown imposed mandatory water restrictions, requiring all cities and towns to cut their water usage by 25 percent. Though agriculture uses more than 80 percent of the state’s water, the regulations merely require farmers to submit “water management plans.”

California’s reservoirs have about a year’s worth of water left. Groundwater levels, seen as a “savings account” that the state can draw from in dry times, are at an all-time low. The US Drought Monitor comes out with weekly drought maps based on satellite imagery, precipitation, and water flow data; the Central Valley—America’s bread basket—is covered in dark red, “exceptional drought.”

What exactly is groundwater, and why are people in California freaking out about it? Groundwater is the water that seeps through the ground when it rains. Over the centuries, it accumulates in vast underground aquifers, with older water found deeper in the earth’s crust. Accessed through wells, groundwater is often compared to a savings account in California—good to have in dry times but difficult to refill. The issue now is that with reservoirs (above ground) so depleted, groundwater use is spiking. Farmers are drilling deeper and deeper for water—using water that fell 20,000 years ago. Usually, groundwater makes up about 40 percent of the state’s freshwater usage, but with the recent drought, that number has leapt to 65 percent. This year, it may rise to 75 percent.

What are the state’s biggest water users? Farming in general, and alfalfa (used to feed cows) and almonds in particular. California grows half of the fruits and veggies produced in the States, including more than 90 percent of the country’s grapes, broccoli, almonds, and walnuts. Here are some of the state’s most thirsty crops:

Alfalfa is a superfood of sorts for cows, and it’s in high demand in the Golden State, which leads the country in dairy production and is also a major beef producer. (Fun fact: It takes nearly 700 gallons of water to grow the alfalfa necessary to produce one gallon of milk, and 425 gallons of water to produce 4 ounces of beef.)  Almonds are second from the top, both because it takes a lot of water to produce nuts (a single almond takes a gallon of water) but also because the crunchy snack is in vogue in the United States and abroad. The water that’s used to grow the California almonds that are exported overseas in one year would be enough to fuel Los Angeles for nearly three years.

Almonds are second from the top, both because it takes a lot of water to produce nuts (a single almond takes a gallon of water) but also because the crunchy snack is in vogue in the United States and abroad. The water that’s used to grow the California almonds that are exported overseas in one year would be enough to fuel Los Angeles for nearly three years.

What about fracking? Fracking uses a lot of water, since the process involves injecting water and chemicals into the earth to release oil and gas. According to a recent Reuters article, California oil producers used about 70 million gallons of water in 2014—about the amount that San Francisco homes use collectively in two days. But that’s just the water from fracking. The amount of water that was produced by California’s oil and gas production in 2014—which is to say, the groundwater that bubbled up during production and wasn’t returned to the original aquifers—was about 42 billion gallons. That’s enough to fuel San Francisco homes for 3 years.

Will we get back the water we lose? Your elementary school teachers didn’t lie to you—the water cycle is really a thing. But as Peter Gleick, the president of the Pacific Institute, explained, the water that California is losing “is still falling—it’s just falling somewhere else.” It’s impossible to know exactly where the water that would normally fall in California is going, but there are plenty of places, especially in the North and Northeast, that have been having abnormally wet years. Scientists are also concerned that climate change is both increasing the likelihood of drought and accelerating its effects: As the earth warms, water evaporates more easily from reservoirs, rivers, and soil.

California is on the coast. Can’t we desalinize the ocean? Because desalinization technology is so expensive and energy-intensive, most water officials—and taxpayers—don’t see it as a viable option. The latest attempt is the Carlsbad desalinization plant, just outside of San Diego, which will be complete in 2016. The project will cost taxpayers $1 billion and produce 50 million gallons of water per day—the largest desalinization plant in the Western Hemisphere—and it will provide just 7 percent of the county’s total water needs.

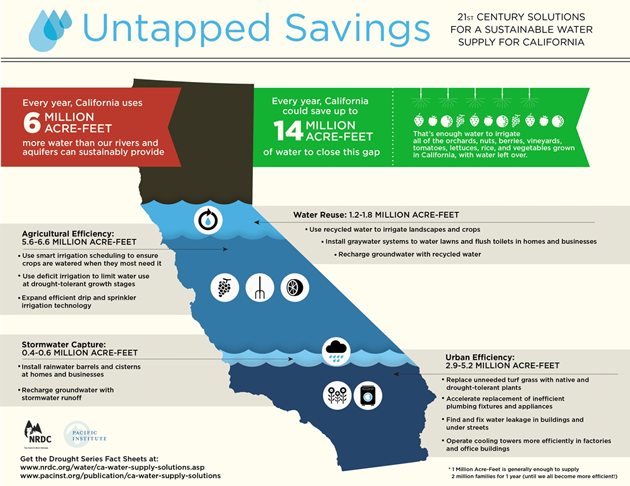

Well, this is depressing. What are viable solutions? There’s no silver bullet, but the good news is that there are some good solutions. This chart, part of a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Pacific Institute, sums up some of the options. California could reduce its water use by 17 to 22 percent with more efficient agricultural water use, including fixes like scheduling irrigation when plants need it and expanding drip and sprinkler irrigation. Urban water use could be reduced by 40 to 60 percent if residents replaced lawns with drought-tolerant plants, fixed water leaks, and replaced old toilets and showerheads with more water-efficient technology. And instead of channeling used water into the ocean, the state could treat it and reuse it—a practice that tends to gross some people out (because of the “drinking pee” factor) but has long been used in Orange County and is becoming more popular as the drought continues.

This article has been updated.