UPDATE (3/20/2017): Late Friday afternoon, March 17, a federal judge dismissed the Des Moines Water Works’ lawsuit discussed below. With the suit having failed, Iowa residents demanding water without excessive nitrate pollution will have to rely on farmers’ voluntary efforts—which include most crucially, as discussed below, the planting of offseason cover crops. A recent Environmental Working Group analysis of satellite data found that just 2.6 percent of Iowa corn and soybean acres utilized cover crops over the winter of 2015-’16. As a result, Des Moines residents “will continue to pay an inordinate amount to clean the waters of the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers that are heavily polluted by agricultural discharge,” Des Moines Water Works CEO Bill Stowe told Iowa Public Radio’s Clay Masters. Meanwhile, the Iowa Legislature is considering a bill that would disband Des Moines Water Works as an independent entity, placing it under control of the city’s government—a move widely seen as retaliation for filing the lawsuit.

Corn is to Iowa what oil is to Texas—so it’s not every day that an Iowa official takes on the state’s biggest industry. But Bill Stowe, CEO and general manager of Des Moines Water Works, has had it with Big Ag. It “rules the roost in this world,” he says. “It’s a nasty business.”

Stowe isn’t just talking smack: Last March, in an unprecedented move, Des Moines Water Works filed a lawsuit in federal court against three upstream counties, charging that they violate the federal Clean Water Act by allowing fertilizer to flow into one of the rivers from which the city gets its drinking water. The suit will likely drag out for years, says Neil Hamilton, director of Drake University’s Agricultural Law Center. But if it succeeds, it will not only force farmers upstream from Des Moines to limit their fertilizer runoff; it could also herald a new era for the Clean Water Act, the ’70s-era legislation that severely limited pollution from heavy industry but left farms essentially unregulated.

Not everyone is so keen on the changes that the lawsuit could bring about. Six-term Republican Gov. Terry Branstad, famously aligned with agribusiness, is fuming. “Des Moines has declared war on rural Iowa,” he snarled at a January press conference. And in May, a group affiliated with the Iowa Farm Bureau called Iowa Partnership for Clean Water began running TV ads praising farmers for their water stewardship and claiming the suit “threatens our land, home, and even your food.”

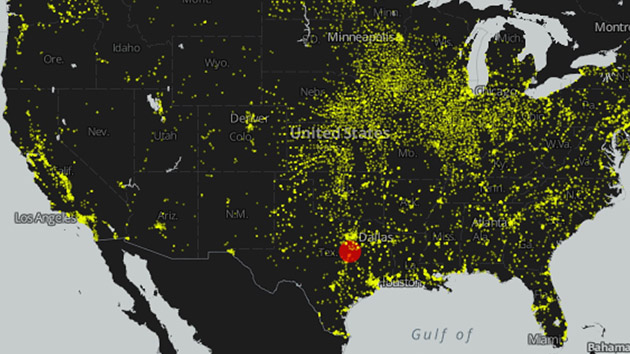

But Des Moines Water Works argues that the real threat to land and food is the chemical that farms are releasing: nitrate. Corn, which uses more nitrogen fertilizer than any other US crop, blankets about 40 percent of Iowa’s landscape. Much of the harvest is fed to the state’s 21 million hogs—nearly a third of the entire US herd—whose nitrogen-rich manure is collected in huge lagoons. Nitrates leaching from fields and lagoons wind up in the rivers that supply more than a half million Des Moines-area residents with water. That’s a problem, because nitrate-laced water has been linked to a range of health problems, including birth defects, blood problems in babies, and cancers of the ovaries and thyroid. Yet nitrogen fertilizer runoff is completely unregulated, in Iowa and most other states.

That leaves cities to cope with the fallout. About 20 years ago, Stowe says, Des Moines Water Works found its water often had nitrate levels above the Environmental Protection Agency’s limit of 10 parts per million. So the agency built what Stowe says is the globe’s largest nitrate-filtration facility. The cost of operating it runs between $4,000 and $7,000 per day—a burden passed on to the city’s residents via water bills.

And the burden has been growing. In 2013, in part because of an unusually wet spring followed by a drought, river nitrate levels surpassed 24 ppm, the highest ever recorded. Des Moines had to run its nitrogen-removal plant for 74 days that year, to the tune of more than $500,000. In 2015, nitrate levels have soared again; at press, the utility company had run the plant for 150 days. What’s more, the nitrate-removal facility is nearing the end of its life, and replacing it will cost Des Moines up to $185 million, says Stowe.

That’s where the utility’s lawsuit comes in: If successful, it could force upstream farms to cut back on runoff. Sarah Carlson of the environmental advocacy group Practical Farmers of Iowa says that if farmers planted cover crops—which suck up and sequester nitrogen after the harvest, keeping it out of water—on 60 percent of the region involved in the lawsuit, it would drastically reduce fertilizer runoff within four years, solving the problem. “Farmers are worried that they’re going to be regulated, and that this is a sign of regulations to come”—fear that is already contributing to a growing interest in cover crops, she adds.

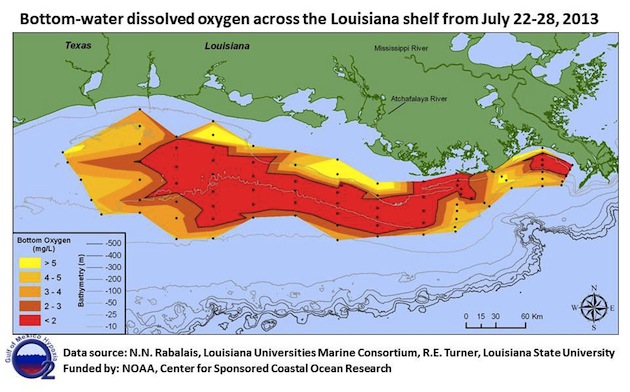

It’s not just Des Moines residents and their angry water chief who stand to benefit from change spurred by the suit. The thousands of pounds of nitrates the plant filters out are dumped back into the rivers downstream, to flow on to other cities. A 2009 University of Iowa survey of nearly 500 private drinking wells found nitrates at or above the 10 ppm limit in 12 percent of them. And once they leave Iowa, most of these nitrates also travel down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, where they help create a dead zone that can be as large as the state of New Hampshire. Meanwhile, public officials in other parts of the Corn Belt—including those in Columbus, Ohio, who warned that pregnant women and infants shouldn’t drink tap water after nitrate levels spiked above federal standards in June—are watching the Iowa suit closely.

Now that Des Moines Water Works has broken the taboo of challenging corn growers on their own turf, other municipalities and citizen groups may be emboldened. Hamilton of Drake University says that the suit “has already inspired a more urgent discussion about protecting soil and water” in Iowa and beyond. If it succeeds, he says, it will “no doubt inspire other jurisdictions [to] look for similarly creative ways” to apply the Clean Water Act.