Matthew Rogers delivers bottles of water in the East Porterville, California.Chieko Hara/AP

This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Bulmario Tapia Madrigal doesn’t want to shower in a stream of dirt. He doesn’t want to cook with bottled water, haul a bucketful to flush the toilet, or wonder if he has enough water to clean the diabetes wounds on his feet. But since his well went dry three months ago, that’s how life has been.

Some relief is coming for the 70-year-old orange picker. On a dry August afternoon, he zips his motorized wheelchair up and down his driveway, anxiously watching a crew of workers. They’re nearly finished connecting his pipes to a new emergency water-storage tank in his front yard, so large it casts a shadow over Madrigal’s red-trimmed bungalow.

“Over by the bakery, there’s a lady who has lived like this for two years,” Madrigal says in Spanish. He sweeps his arm toward the street, where the dusty front yards of neighbors are also occupied by hulking water tanks. “Anyone who used a well before no longer can.”

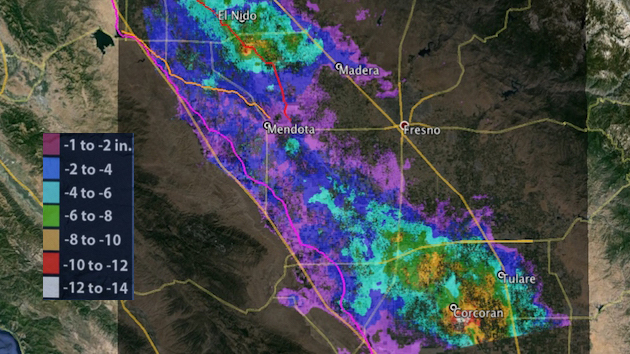

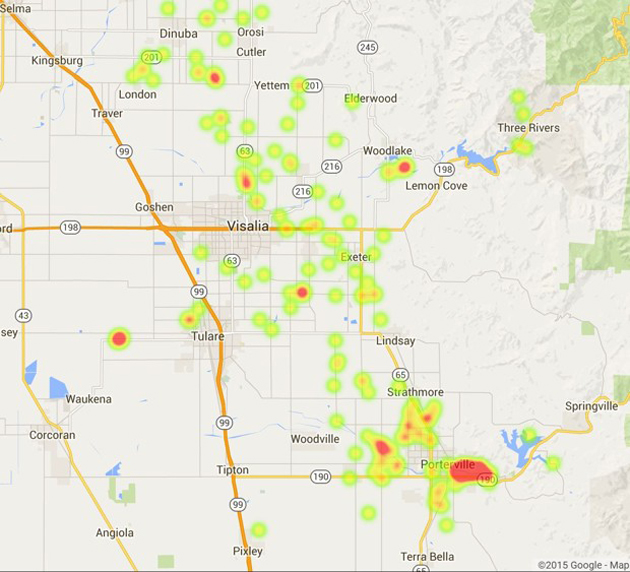

This is not a developing nation. This is East Porterville, California, where more than 500 wells have dried up since the beginning of the state’s worst-on-record drought four years ago. It’s home to most of the 1,675 wells (and counting) that are sucking dirt in Tulare County. Tulare is one of the eight inland counties that make up the San Joaquin Valley, the richest agricultural region in the world.

Tulare County has been working with local nonprofits to provide and refill storage tanks for low-income families who’ve run out of well water. There are an estimated 1,750 households in East Porterville, and at least 35 percent of residents live in poverty. For people like Madrigal, the tanks are literally lifesavers.

But they’re also a mark of disparity. If it weren’t for those tanks, you might never know that where Madrigal lives is separate from the city of Porterville. Even though his address reads “Porterville,” he lives on unincorporated county land adjacent to municipal limits. That means he is just beyond the reach of Porterville’s formal water district, which has continued to serve its more than 16,000 customers with clean, running water without issue throughout the drought.

Dry wells are spreading beyond East Porterville. There is a pattern to the spread: Poor, unincorporated, predominantly non-white communities are the ones struggling. Caught between city and county, water issues are nothing new to these densely settled places. Many have dealt with a lack of appropriate water infrastructure—and contaminated supplies—for decades. The drought is only the newest, most visible layer in a strata of disparities.

“The land is half and half here,” Madrigal says. “Half dry, half alive.”

Madrigal and his neighbors have long relied on wells that pump water from the ground, the same reserves used by surrounding farms to keep crops lush. Since the beginning of the drought, farmers have drilled their wells deeper, sucking up more of the ground supply. With scarce rain, the aquifer hasn’t been recharged. Tulare County’s water table is shallow, relative to other parts of the San Joaquin Valley. So more and more wells are coming up empty.

It’s tempting to call what’s happening here a slow-motion natural disaster. It is also tempting to point the finger at farmers, as so much media coverage of the drought has.

But those hit hardest by the drought have been vulnerable for decades. The San Joaquin Valley’s history of Wild West land-use planning, its governance structures, and the political disenfranchisement of an entire class of citizens have created a human-made crisis.

The sprawling, underserved San Joaquin Valley

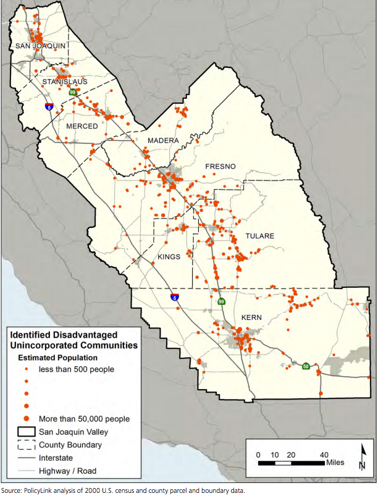

A recent report by the California nonprofit PolicyLink counted 525 poor, densely populated, unincorporated communities throughout the San Joaquin Valley, inhabited by some 310,000 people. Some, like East Porterville, are on the fringes of larger towns. Others are islands within city limits. And still others are scattered to the hinterlands, far from anywhere else.

Sixty-five percent of the population in these places are people of color. Sixty-four percent are low-income.

Waves of black and Latino farmworkers settled many of these communities in the first half of the 20th century, sometimes living in tents or shacks until they had the means to build their own homes. Until the 1960s, land use—an authority reserved for local governments in California—was almost totally deregulated in the region. Hundreds of subdivisions sprang up throughout the San Joaquin Valley, with little thought about the future impact of disconnected sprawl.

Many of these places probably looked good to poor farmworkers: inexpensive, close to the fields, with low taxes and little government oversight. Outside the city, you could keep the kinds of animals you wanted, and the kinds of vehicles. What land-use restrictions existed were barely enforced.

“There are lots of good reasons to build outside the city,” says Eric Coyne, an official with the Tulare County Resource Management Agency. “At one point, a shallow well might have been sufficient for a family.”

It’s true: For most of the past century in California, there has been rain to replenish groundwater supplies. And there used to be more surface water. East Porterville, for example, is just across from the once-overflowing Tule River.

Carrie Bonner was seeking field work and an affordable place to live when she came to the Fresno County subdivision of Lanare in 1948. At that time, it was mainly her family and other black families, settling in substandard farmworker housing until they’d saved enough to buy some land.

“You got to choose where you put your house,” the 91-year-old says. “There was no one saying, ‘Go here’ or ‘Go here.’ You dug your well. It was a community effort.”

Lanare sits right next to Riverdale, a wealthier community settled at around the same time by white dairy owners. Some research suggests that Riverdale real estate agents excluded people of color from settling there in the first half of the 20th century, or at least encouraged them to look elsewhere. Certainly, the poverty that these farm workers faced locked them out of pricier lots. Elsewhere in the San Joaquin Valley, racially restrictive covenants did expressly keep people of color out of white communities.

Michelle Anderson, a Stanford University public law scholar who focuses on state and local governments, writes in the UCLA Law Review about the development of these subdivisions:

Neglect by white officials, often compounded by community need to keep housing costs low, resulted in a lack of rudimentary infrastructure, including paved streets, sewers, utilities, and water. These unplanned, unregulated communities retained a rural character—embodied by backyard husbandry and subsistence farming—that reflected the importance of self-sufficiency during times of employment insecurity.

Over the years, that government neglect was explicit in some cases. An ordinance in Tulare County’s 1971 general plan (updated only within the last decade) is particularly grim, intentionally aiming investment away from 15 poor, unincorporated communities—assuming that they would eventually depopulate. The plan reads:

Public commitments to communities with little or no authentic future should be carefully examined before final action is initiated. These non-viable communities would, as a consequence of withholding major public facilities such as sewer and water systems, enter a process of long term, natural decline as residents depart for improved opportunities in nearby communities.

Today, 13 of those “non-viable” communities are still around. They include Seville, which went into a water shortage emergency during the week in August that I visited the San Joaquin Valley. They also include East Orosi, Farmersville, Yettem, Monson, and Exeter—all places where wells have dried up in the last year. Far from disappearing, some of these communities have even grown since the 1970s, surviving on the insufficient infrastructure that marked them for disinvestment. Many are now adjacent to cities that crept up toward them. By density measures, some read like suburbs. They are not temporary places, as Tulare County had hoped.

Clearly, steering funds away has not encouraged residents to “depart”: Property values are so low that it’s hard for residents to move, even if they wanted to.

Which not everyone does. The characteristics that attracted residents to county subdivisions in the first place—their low cost, minimal government oversight, and spirit of self-sufficiency—still appeal. Many residents retain a good deal of pride in a place they’ve built with their own hands.

Yet for water (and other types of infrastructure), many of these poor, county subdivisions remain largely self-reliant—using either small, private wells, like in East Porterville, or community water systems that source from a few larger, common wells. The recent drought is hardly the first time that access to drinking water from these wells has been compromised.

When water is available, it’s not always safe to drink

Surrounded by farmland, many unincorporated communities have had fertilizers, pesticides, and livestock waste leaking into their groundwater for decades. The San Joaquin Valley has the highest rates of drinking water contamination in the state, and the largest number of public water systems found in violation of EPA limits for nitrates, arsenic, fecal coliform bacteria, and other contaminants. The health effects can be severe.

Unincorporated places are particularly at risk for contamination, since their wells tend to be shallower. The drought is exacerbating this problem: With less water, concentrations of groundwater contaminants are spiking.

All of this, despite the fact that California has legally declared that every citizen has a right to safe drinking water.

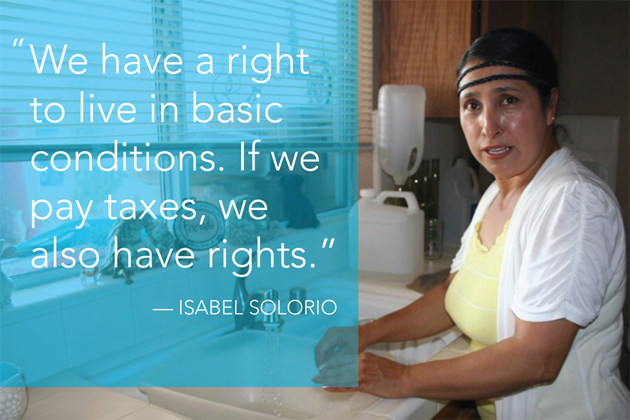

In Isabel Solorio’s spartan kitchen in Lanare, the countertops are lined with plastic gallon jugs of water. Solorio stands at her sink, letting water run from the tap. “Sometimes it’s slimy,” the 50-year-old says, rubbing her fingers in the stream. She puts her fingertips to her nose, hesitantly. The water has a faint sulfuric mustiness.

In the nearly 28 years she’s lived here, Solorio says she can’t remember a time when the water was safe to drink. Levels of arsenic (which occurs naturally, unlike nitrates from runoff) in Lanare’s water supply are are well above the EPA limit. For her, the drought is just another piece of a world in disorder. “The atmosphere and the Earth are sick,” she says in Spanish, looking out the kitchen window. There’s a children’s play structure in her yard and a sea of alfalfa fields beyond it. “And people are sick. All these dots connect.”

In addition to cleaning houses for a living, Solorio has acted as Lanare’s lead community activist, convening residents and legal advocates on a monthly basis to fight for safe drinking water and other basic services (Lanare also lacks a sewage system, street lights, and sidewalks).

In 2002, the community won a $1.3 million federal grant to construct an arsenic treatment plant, which took five years to build. But the project was mismanaged, and after the plant opened, operational costs skyrocketed for the low-income community of 600. The plant ran for just six months before shutting down, and now sits disused in a chain-link cage next to Lanare’s community center. The community’s water system—which sources from two common wells—then went into state receivership.

The water that comes out of residents’ taps is not safe to drink. Yet Solorio and her neighbors still pay $54 a month for their water bills, largely to pay off debts incurred by the plant. Meanwhile, they rely on jugs of water delivered and paid for by the state.

Will the plant ever come back into commission? Phoebe Seaton, co-director of the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, which provides legal and advocacy services to Lanare, darkly jokes that the best solution might be to turn it into a jungle gym.

The county won’t budge

It’s not clear how Lanare is going to move forward. In the absence of a formal town government, a special “community services district” is supposed to run Lanare’s water system after its receivership ends. That “CSD” consists of volunteers, one of whom is Solorio’s husband, who also works full-time as a contract welder on farms. Right now the CSD doesn’t even have enough members to constitute a quorum.

Could the county intervene? Lanare residents say that officials had hardly even visited until last July, when Fresno County Supervisor Buddy Mendes sat down for a meeting in the community center after repeated invitations. Residents aired their grievances, and Mendes listened. But when one resident asked what concrete steps he was was going to take to resolve Lanare’s problems, “he told them the best thing that could happen was that he had come there,” Veronica Garibay, the Leadership Counsel’s other co-director, recalls.

Mendes says he thought it was a productive meeting. “I told them to straighten out their affairs,” he says. He feels Lanare is on its way to being solvent, and “fixing its culture so that everyone pays their water bills,” a concept that had to be “pounded into people.” Beyond that, Mendes says it’s up to the community to figure out how to get their needs met.

County governments in the San Joaquin Valley aren’t legally responsible for providing urban infrastructure, nor are they set up to do so. “We could have designed government schemes where counties are really tailored to rural government, but by and large we didn’t,” says Anderson, the Stanford legal scholar. She points to 1964’s “One Man, One Vote” US Supreme Court decision (currently being challenged) as a critical reason that it’s so difficult for rural areas to leverage county resources. When it comes to voting on how money is allocated, city voters outnumber rural voters heavily.

When asked how Fresno County might be able to help Lanare obtain safe drinking water, Bernard Jimenez, Fresno County’s deputy director of planning, echoes Mendes’ sentiment. “The county does not have the resources or the funding to provide services to all the unincorporated communities,” he says. “That’s just the way it works.”

But compare the people who are supposed to run Lanare’s water system to the fully trained, paid employees of a municipal water district.

Then add to that the challenge and cost of maintaining a safe water system—an inherently expensive endeavor, even more so for a poor community of 600 that lacks economy of scale—and it’s incredible that the residents of Lanare have made it this far.

It’s even more incredible that, as the drought drags on and water becomes all the more precious, there’s been little meaningful government intervention.

“It is inspiring for people to go these distances without government support, in a country where so many forms of infrastructure are subsidized through taxes,” says Anderson. “But there are limits to individual self-reliance. There are things people cannot build all by themselves.”

City connections

Government neglect in the San Joaquin Valley’s unincorporated communities is certainly not limited to counties. As cities in the San Joaquin Valley grew and annexed more surrounding land, they often avoided the poorest communities as they did so. That’s generally how “island” communities—unincorporated patches within city limits—formed.

For those communities, and for those like East Porterville on the fringes of larger cities, the question of why the city can’t just extend some pipes can seem bewildering.

At the chain-link fence at the front of his property, Madrigal points to a clearing of pines just beyond the last house on his street. “Just right over there is the supply cut-off,” he says. “I believe there’s water for the town. It’s just this area that’s left off.”

The workers in his yard finish their work. They flip the switch on the pump they’ve installed and water starts coursing through Madrigal’s pipes for the first time in months. He tells me I can go inside to check the kitchen sink. I flip the handle up. Sure enough, water flows out, clean and pure. But Madrigal’s supply is limited to what’s in the tank. So I quickly turn off the tap.

The drought is dragging on. Water is only becoming more precious and more expensive. Questions of annexation and consolidated water services are fundamental to the debate around how these communities are to survive. State and local governments are beginning to ramp up efforts to invest in and connect unincorporated communities to larger, more reliable systems. But in a region plagued with a legacy of questionable planning decisions, there’s plenty standing in the way.

“We all want to serve these people,” says Coyne, the Tulare County official. “The question is, how do we get those funds?”

An equally important question is: Where do they get the water?

Next week, I’ll try to answer both.