The science behind climate change is indisputable. With more than 190 countries signing off on a historic climate deal, the case for action has never been more clear. And yet in the United States, one of the major political parties and most of its presidential candidates stand firmly against even market-friendly policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Why?

This question has vexed pundits, academics, and scientists for decades. New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait recently examined new research from the University of Bergen in Norway and provocatively asked, “Why Are Republicans the Only Climate-Science-Denying Party in the World?” One reason, he argues, is that “the virulence of anti-government ideology in the United States has no parallel anywhere in the world.” While this is certainly true, it can’t explain the fact that a recent survey and other data suggests that the majority of Republican voters accept the science behind global warming.

Here’s another possible explanation for the GOP’s intransigence in accepting and addressing climate change: the overwhelming influence of its donors, which stifles the preferences of the party’s majority.

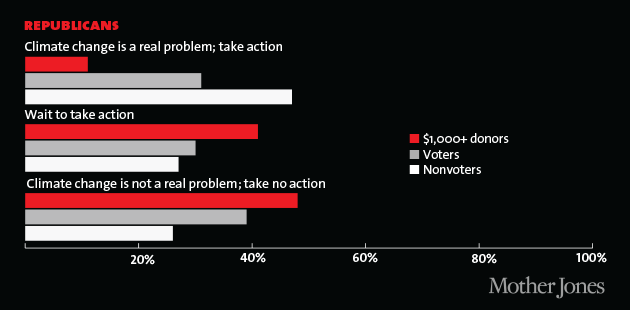

Using the 2012 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, a survey of more than 50,000 Americans funded by the National Science Foundation and designed by scholars from more than 40 universities, we compared the preferences of Republican voters, nonvoters, and donors who gave $1,000 or more political contributions in the previous year. (The nonvoters and voters were not donors.)

Survey respondents were asked which of the following five options was closest to their own opinion:

• Global climate change has been established as a serious problem, and immediate action is necessary.

• There is enough evidence that climate change is taking place and some action should be taken.

• We don’t know enough about global climate change, and more research is necessary before we take any actions.

• Concern about global climate change is exaggerated. No action is necessary.

• Global climate change is not occurring; this is not a real issue.

The data shows stark divides among Republicans, with nonvoting supporters of the party most likely to accept climate change and big donors most likely to deny the reality of climate change. Republican voters are essentially split into thirds between taking action, waiting, and rejecting the science behind climate change. More than 30 percent of voters and 47 percent of nonvoters believe the science is well enough established for action. Yet only 15 percent of donors support action. And almost half of donors are flat-out deniers, entirely rejecting the science of global warming.

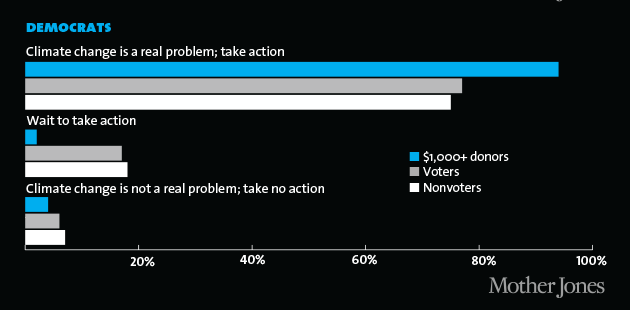

On the Democratic side, the divide between donors and nondonors is much smaller: 77 percent of Democratic voters who are not donors and 94 percent of Democratic donors say they support action on global warming.

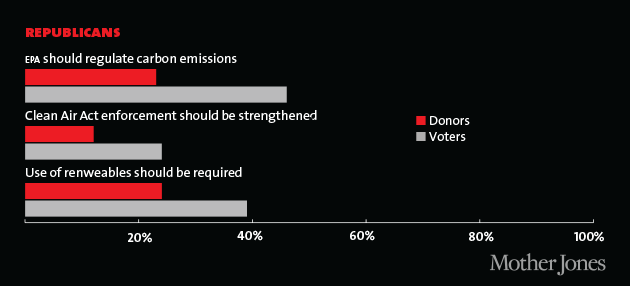

According to the 2014 CCES, which asked different questions on climate change, most Republican donors express little interest in taking action on global warming even when presented with specific policy proposals. Just 23 percent of all Republican donors think that the Environmental Protection Agency should regulate carbon dioxide emissions, compared to nearly half of Republican voters. Just 12 percent of donors support strengthening enforcement of the Clean Air Act, compared with 24 percent of the party rank-and-file. And while nearly 40 percent of Republican voters support requiring the use of renewable fuels, just one in four Republican donors support such a policy.

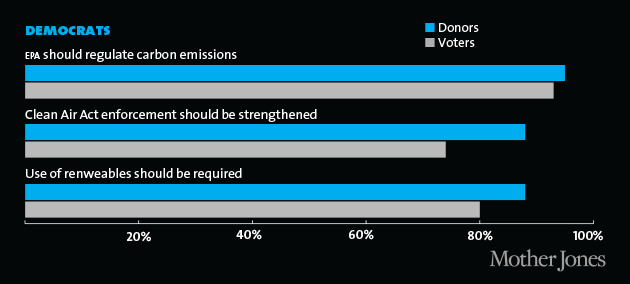

On the Democratic side, voters and donors have close views on these policies, though donors generally favor stronger environmental policies than the rank-and-file.

A survey of donors who gave more than $200 in 2012 performed by Michael Barber, a political scientist at Brigham Young University, further confirms the CCES data. He finds that only 26 percent of Republican donors support implementing requirements to lower the amount of greenhouse gases produced by American businesses. Fully 70 percent of Republican donors support repealing the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gasses.

Donors’ attitudes toward climate change also have implications for environmental justice. A recent AP investigation estimated that 90 percent of donations over $200 in 2012 came from majority white Census blocks. In a recent report from the think tank Demos (where Sean is a research associate), Adam Lioz noted that the power of the overwhelmingly white donor class frequently undermines steps towards racial justice. Climate change is no different. In the 2012 CCES, 55 percent of white donors of both parties said that global warming has been established and action should be taken, compared to 71 percent of non-white donors. And in the 2014 CCES, 58 percent of white donors supported EPA regulation of carbon emissions, compared to 71 percent of non-white donors.

There are numerous reasons why the United States has failed to take action on climate change, from collective-action problems to the difficulty of making immediate changes to stave off what may seem like a far-off catastrophe. However, it’s increasingly clear that money in politics is also a key impediment to action. This data suggests that progress on climate change has been thwarted by the Republican Party catering to a small and extreme donor base that is overwhelmingly opposed to facing reality.