<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-131090639/stock-photo-electric-lighting-effect-abstract-techno-backgrounds-for-your-design.html?src=gsSm2_D_Xq4YNGWvETJFYQ-1-1">Ase</a>/Shutterstock

The United States leads the world in the number of electric vehicles on the road, but the count is still tiny: about 350,000. That’s less than 1 percent of all passenger cars and trucks in the country. Recent market research suggests that number will climb steadily over the next several decades. But will it climb fast enough? When it comes to fighting climate change, that could turn out to be one of the most important questions of the next few years.

On April 22, world leaders gathered in New York City to sign the Paris Agreement on climate change, in which they vowed to keep global temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, a limit the world is already more than halfway toward exceeding. Meanwhile, energy experts have begun to map out the fine-grain details of what meeting that goal would actually require. And it’s becoming increasingly clear that electric vehicles have an indispensable role to play.

It turns out that one of the most immediate societal changes for average Americans in a climate-savvy future would likely be the electrification of just about everything. In other words, the hope of the planet could lie in a force—electricity—we’ve known about for hundreds of years.

That might sound strange, given that electricity production is the No. 1 source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Coal- and gas-burning power plants are still our main sources of electricity, and in some parts of the country the power grid is so dirty that electric vehicles might actually cause more pollution than traditional gas-guzzlers.

But thanks to the explosive growth of solar, wind, and other renewable energy technologies, electricity is getting cleaner all the time. Over the last decade, the share of total US electricity production from renewables (including hydroelectric dams) rose from about 9.5 percent to more than 14 percent, with year-to-year growth getting faster all the time. So there’s a good case to be made for phasing out the other types of fossil fuel use in our daily lives—particularly gasoline for cars and oil and gas for heating buildings. We should be using electricity instead—even if that means using more electricity overall.

That’s a key finding of the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project, an international consortium of energy researchers that produced a detailed technical study of how to cut US greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent compared with 1990 levels by 2050—the change necessary if Americans hope to do their part to stay within the two-degree limit. The report found that it’s technically possible for the United States to meet that target, at an annual cost of about 1 percent of GDP, without sacrificing any “energy services.” That is, the report assumes we’ll still drive and have houses and operate factories the same as we do today. But to do so will require a major boost in electrification—which will in turn require that the US produce about twice as much electricity as it currently does—while reducing the carbon emissions per unit of energy down to just 3 to 10 percent of their current levels. In other words, at the same time we’re electrifying everything, we need to continue to clean up the electric grid and double down on energy efficiency, especially in buildings.

“You can’t get to a level of emissions that’s compatible with 2C or less unless you do all three of those things,” said Jim Williams, one of the report’s lead authors and chief scientist at the private research firm Energy and Environmental Economics.

We get energy from fossil fuels in two basic ways: either by burning it in a power plant to create electricity that gets used elsewhere, or by burning it directly where it’s needed—i.e., your car’s internal combustion engine or a gas-fueled stove. Williams’ basic idea—which has also been advanced by other leading energy economists, particularly Stanford’s Mark Jacobson—is to ax that second category as much as possible, while simultaneously “decarbonizing” the electric grid by replacing fossil fuels with wind, solar, and other renewables.

Williams’ model doesn’t assume that all fossil fuel consumption goes completely to zero. A small portion of electricity could still come from natural gas plants; some oil and gas could still be used for manufacturing and industrial purposes; and airplanes, freight trains, and ocean liners may still rely mainly on petroleum. But by the middle of the century, the total “budget” for fossil fuels will become so small that they need to be limited only to uses that are absolutely unavoidable. Everything that can run on electricity needs to do so. Cars and buildings are low-hanging fruit. And despite gradual fuel efficiency improvements in cars over the last few decades, Williams said, there’s ultimately no way to make an oil-burning internal combustion car engine efficient enough to fit in the tiny fossil fuel “budget.”

“At some point you can’t continue to do direct combustion of fossil fuels, even if it’s efficient,” he said. “There is a point where you have to get out of direct fossil fuel combustion to the maximum extent.”

Ending direct combustion of fossil fuels would take a massive bite out of greenhouse gas emissions: Put together, buildings, transportation, and industrial uses account for more than half of the country’s carbon footprint.

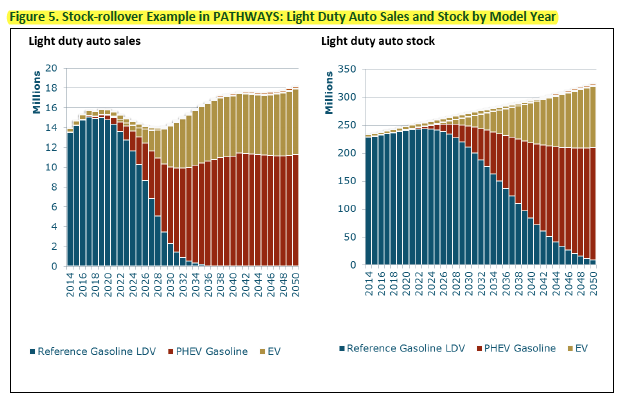

In practical terms, the most important element of that transition would be bringing electric vehicles off the sidelines and into the mainstream. The charts below, from the report, illustrate what that transformation would look like. It’s important to note that these charts are not a projection of what the authors think will happen, but rather a prescription for what they think should happen. In the left chart, you can see that starting in the mid-2020s, sales of gas-powered cars (blue) fall off dramatically in favor of hybrids (red) and fully electric vehicles (gold). On the right, you see that by the mid-2030s, there are more electric cars and hybrids on the road than gas-powered cars:

At the same time as this transformation is happening on the road, your gas stove will be swapped for an electric one; ditto the gas furnace in your basement. Gas stations will close and be replaced by charging stations. Machinery in factories that uses oil and gas will be largely replaced with electric equipment. Your propane or charcoal grill could be replaced by a George Foreman…you get the idea.

These are big shifts, but Williams said they probably won’t actually be very noticeable to most people. How much do you really know about what’s under your hood? Would you really notice if your basement held an electric heat pump instead of a gas furnace?

“The carbon aspect is in the guts of it that people don’t really look at,” he said. “The good news is that even if we continue to live like we’re living, we have the technology, we have what it takes to quit emitting so much CO2 to the atmosphere.”

Still, we’re not yet on pace to meet the goals laid out in the DDPP report. In a recent market forecast from Bloomberg New Energy Finance of global electric vehicle sales—a realistic picture of what the future actually holds, given current policies—global sales of electric and hybrid vehicles in 2040 are still only 35 percent of total car sales, instead of close to 100 percent in Williams’ model.

How do we get on track? Williams argues that policymakers need to start spending less energy worrying about fuel efficiency for oil-powered cars and focus instead on speeding up the transition to electric vehicles. That’s something the Obama administration has only scratched the surface of, so it could be an area of focus for the next president. Power grid operators, too, need to start planning for a future in which there could be major demand for electricity in sectors (i.e., electric cars, home heating, etc.) that are small now.

“We’re not used to having a whole lot of our electricity being used by sectors that currently don’t exist,” Williams said. “We need to already be thinking about that. If we don’t start planning now, we’ll run into dead ends.”

Have more questions about electricity? We’ve got your answers in this special podcast episode with our engagement editor, Ben Dreyfuss: