ilovedust

Let me guess: You don’t cook as much as you wish you did. The whole rigmarole, from menu planning to navigating the store to chopping and cleaning everything up, seems like a time-sucking ordeal. Yet you’ve heard the messages: Home-cooked meals engender a healthier relationship with food and a richer family life.

But if you’re like most Americans, achieving those kitchen aspirations will require some help. Left to our own devices, we now spend half our food dollars eating out. And even when we stay in, we often revert to takeout—only 50 percent of the main dishes served at home are cooked there.

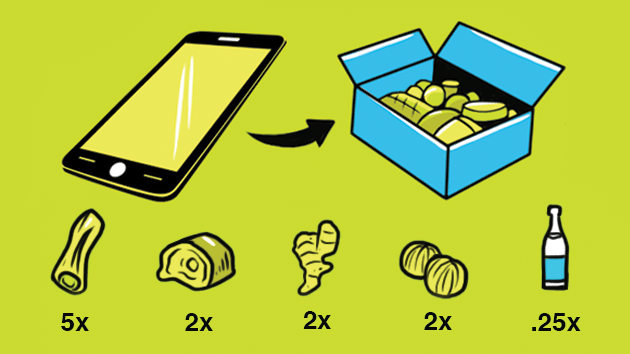

Silicon Valley has just the thing for you. For a fee, more than a dozen well-funded startups will overnight you a box with a simple recipe and all the ingredients, even perishable stuff like meat, precisely measured and ready for the pan.

These “meal kit” services, as they’re known, exist to deliver the thing we miss about cooking—the thrill of transformation with fire—while stripping away much of the drudgery. “Throw a dart,” and you can find a company catering to just about any food preference, says Brita Rosenheim, founder of a consulting firm focused on food-related tech companies. In addition to big names like Blue Apron, there’s Sun Basket, catering to paleo and gluten-free tastes, and Purple Carrot, whose vegan kits are fronted by home cooking champion Mark Bittman. Chef’d woos the starry-eyed with recipes by culinary celebrities. Even Bittman’s former employer, the New York Times, is getting into the game. As part of a new partnership with Chef’d, fans of the Times food section can order meal kits based on recipes ripped from the pages of the “paper of record.”

Venture capital firms—eager to disrupt the trillion-dollar US food economy—are drenching the space with cash. Rosenheim reports that top meal-kit companies have attracted massive investments—$477.6 million in 2015, more than triple their 2014 haul. In January, the market research firm Technomic estimated that these companies’ 2015 revenues hit $500 million, and projected they would rise by a factor of 10 within five years, positioning them to “change the way consumers think about food at home.”

But it remains to be seen whether enough at-home short-order cooks will bite. So far, “very few, if any,” of these meal-kit companies “are cash-flow positive,” Rosenheim suspects. She predicts a “dramatic” shakeout this year, with “larger players gobbling up some of the smaller players” and others shuttering altogether.

The problem is pretty fundamental: Food businesses generally operate on razor-thin profit margins. And while meal-kit purveyors don’t have the huge real estate expenses that restaurants do, they face the pricey proposition of shipping perishable goods across great distances. If a recipe calls for parsley, that sprig will typically arrive in its own plastic bag; a tablespoon of butter for finishing a sauce requires a tiny plastic container. And keeping the whole thing cold for a long-distance journey, including that shrink-wrapped salmon fillet, typically means gel-filled ice packs and a whole lot of packaging.

The math can work, Rosenheim says, but only at massive scale. And reaching that scale is expensive: Meal-kit players spend as much as $100 to attract each new customer. Then they face churn: customers drifting away, either to join up with a rival service or drop out. Some will start to wonder why they’re paying a premium—up to $15 for one serving—for meals that require their labor. Why not just fire up one of the zillions of new prepared-food delivery apps, funded to a tune of more than $457 million last year, instead?

A few winners will emerge, and they’ll probably diversify their models to offer fully prepared meals. But in the end, venture capitalists may tire of this fad. Ultimately, investing in a meal-kit company “is not as sexy as it seems,” Rosenheim says. “It’s more like running a restaurant or a catering business.”

Bittman, who shocked the food world in late 2015 by leaving his perch as a columnist at the New York Times to become the chief innovation officer at Purple Carrot, is undaunted. When I talked to him in February, he viewed his new gig as the next logical phase of a 25-year career trying to convince people that learning to cook is doable and worth the trouble. “If they graduate and say, ‘I’m now a cook and I no longer need Purple Carrot,’ of course that costs us—but that’s a happy ending,” he said.

But several months later, Bittman left his post at Purple Carrot to “move on to new things,” he told me this week. Bittman retains an ownership stake in the company. “I still feel the same way about meal kits, and I wish Purple Carrot the best,” he added.

For now, with all that venture capital sloshing around, free stuff abounds for curious would-be cooks. Last time I checked, Green Chef, which boasts nearly 100 percent organic ingredients, was offering a deal: “Order 2 meals, get 4 free on your first order!” Get ’em while they’re still hot.