I used to tune out when my father would go on about eminent domain: how his immigrant grandparents had built up a modest homestead with two houses, three grown children, and a flock of chickens on the banks of the Bronx River. And then, around 1913, how the government had seized the property to make way for the Bronx River Parkway. That the episode still rankled after almost a century just seemed like a manifestation of my father’s cranky late-life conservatism.

That was before I found out about Madison Grant.

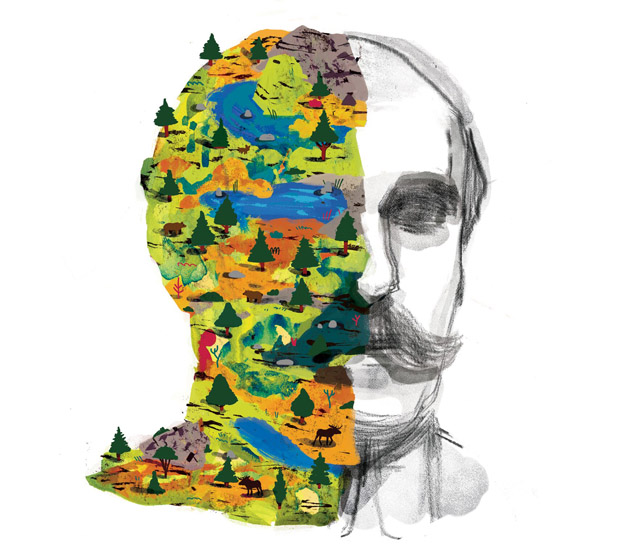

Madison Grant

Wikipedia Commons

It’s a name you should be hearing a lot this year because of the centennial of the National Park Service—in many ways a product of Grant’s pioneering work as the greatest conservationist who ever lived, according to one early Park Service director, and a creator of “the park concept,” in the words of another. But you probably won’t hear Grant’s name so much as whispered, because his peculiar line of thinking also helped lay the groundwork for the death camps of Nazi Germany.

Born in 1865, Grant enjoyed a blue-blood Manhattan childhood thanks to his mother’s family wealth and his father’s reputation as a doctor and Civil War hero. At 16, he went to Germany for four years of private tutoring before coming back for Yale and then Columbia Law School.

Grant was a handsome, urbane figure with a thick mustache and steady, deep-set eyes and a reputation as a ladies’ man. He set up a Manhattan law office but rarely practiced. Nor did he ever hold public office, despite his keen political interests. Big-game hunting was his real passion, according to the definitive 2008 biography Defending the Master Race, by historian Jonathan Spiro, and he recognized early on that reckless overhunting was driving many species to extinction. Wealth, social connections, and his sharp mind soon earned him membership among such early hunter-conservationists as Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, and George Bird Grinnell in a spectacularly influential little group called the Boone and Crockett Club.

By 1895, Grant was overseeing construction of the Bronx Zoo, dedicated to the preservation of North American species, and had founded its parent organization. (The Wildlife Conservation Society, as it’s now known, likewise never mentions Grant’s name.) Among his many other initiatives, Grant helped launch the campaign to stop the last of California’s magnificent redwoods from being logged, worked to save the bison (restocking the Plains with bison from his zoo), and pushed for the creation of the Denali, Olympic, Everglades, and Glacier national parks.

This legacy might sound like fodder for Park Service accolades and PBS documentaries, except for one problem: After 1908, Grant began extending his efforts on behalf of North America’s native species to what he considered its “native American” people—not Indian tribes but northern Europeans, preferably “of Colonial descent.” In 1916, he published The Passing of the Great Race to call attention to the plight of the “Nordics,” a word he helped popularize. “Unlimited immigration” and intermarriage, he warned, were “sweeping the nation toward a racial abyss.”

The book was a 476-page pseudoscientific compendium of stereotypes. Black men were “a valuable element in the community” so long as they remained “willing followers who ask only to obey and to further the ideals and wishes of the master race.” The Irish tended to be intellectually “inferior,” and “the Slovak, the Italian, the Syrian and the Jew” were “social discards.” Having seen New York City’s Jewish population surge from 80,000 to more than a million in just 30 years, Grant was especially enraged at “being literally driven off the streets…by the swarms of Polish Jews.”

Grant’s book ought to have been a national scandal. But eugenics, the idea that human stock could be improved much like livestock, was then becoming almost an establishment religion. So The Passing of the Great Race was published by Scribner’s and edited by Maxwell Perkins (who later edited F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway). The president of the American Museum of Natural History wrote the preface, and former President Theodore Roosevelt provided a blurb (“a capital book“).

Grant parlayed his rising influence as a eugenicist into a series of punitive measures aimed at “inferior races and classes.” The Bronx River Parkway, for instance, was originally about cleaning up a polluted river and adding a roadway through newly picturesque landscapes. But Grant’s commission carefully planned the project to take out “the wrong sort of development”—”Italian shacks” like my great-grandfather’s, and neighborhoods populated by “Negroes.”

Others lost far more than their homes under Grant’s influence. Many states pursued his recommendation to apply mandatory sterilization “to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased and the insane and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings.” Grant was also key to the passage of a 1924 law restricting immigration by groups he deemed undesirable, including Asians and Arabs.

When the Nazis established their compulsory sterilization program in 1933, they said they were following “the American pathfinders Madison Grant” and a Grant disciple, Lothrop Stoddard. Hitler once supposedly wrote to Grant to say his book had become “my Bible.” Grant died in 1937, too soon to see his theories turned into mass murder. But among those he inspired was Karl Brandt, the physician behind the Nazi program of forced euthanasia. At Nuremberg, Brandt’s lawyers presented The Passing of the Great Race as evidence that the Nazis had merely done what an American scholar had advocated.

Conservationists would understandably rather forget all this. But it’s worth remembering because the movement has always struggled with elitist and exclusionary elements in its ranks. Among other things, this country invented and exported worldwide the model of uninhabited national parks—together with its ugly corollary, forced removals of indigenous populations. It’s also worth remembering Grant’s history because minority groups remain vastly under-represented—just 22 percent of all visitors at last count—in our national parks, and even more so in the leadership of environmental agencies and nonprofits. To change that, the conservation movement needs to acknowledge that the ghost of Madison Grant still haunts the natural wonders he helped protect.