stellalevi/Getty Images

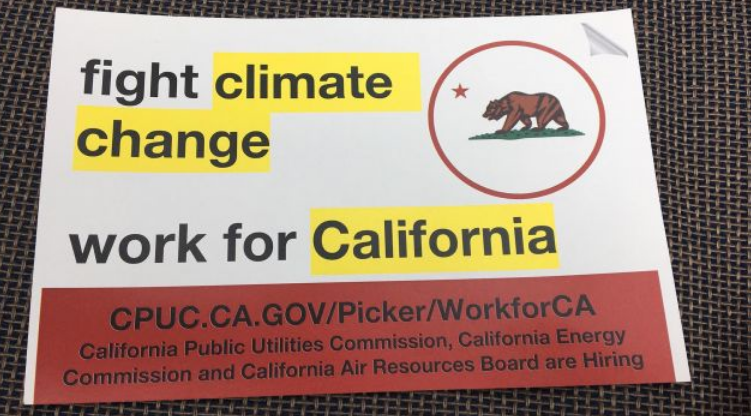

Michael Picker stood in the freezing cold outside of the Environmental Protection Agency early Thursday morning passing out fliers that read, “Come work for California. Fight climate change.”

Picker was far away from his home in Sacramento, where he is the president of California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), for meetings with the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners. He decided to try to recruit demoralized EPA staffers, who are facing deep program cuts and controversial new leadership. The EPA’s new administrator, Scott Pruitt, has a long record of opposing the agency’s work.

Picker hopes to entice them to work for a state government with one of the most ambitious climate goals in the country. California is looking to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. The flyers pointed people to a webpage to sign up for more details.

Picker’s timing was good: The White House had just unveiled cuts of 31 percent to the agency’s budget, the smallest proposed budget in 40 years. In Michigan, Trump had announced his plan to roll back the EPA’s fuel efficiency standards for cars. And, any day now, the president’s executive orders gutting EPA’s climate change work are expected to be announced.

“I don’t agree with the president and certainly am not going to shy from an opportunity to give people good work to pursue their goals,” Picker told Mother Jones. He’s hoping to find a handful of DC-based federal workers willing to move west to work for the utility energy regulator and add some fresh insight and much-needed talent to the CPUC.

Picker squeezed in the EPA visit—and another one at the Department of Energy—because the CPUC faces a hiring problem. CPUC needs to replace about 60 percent of its staff in the next three to five years because its older workforce is approaching retirement. Two other government agencies that work on helping the state cut greenhouse gases—the California Air Resources Board and California Energy Commission—are also recruiting for the same reason. But CPUC was the only agency targeting EPA employees; Picker joked representatives from the other regulators probably just didn’t want to wake up that early.

The unusual hiring drive isn’t a political stunt, argues the California energy regulator, even if it might appear to be another example of California’s antagonism towards Trump. Gov. Jerry Brown (D), who appointed Picker, promised after the presidential election, “If Trump turns off the satellites, California will launch its own damn satellite.” Trump has opened the door to weakening the EPA and Department of Transportation’s fuel efficiency standards, and lawmakers in California are poised to fight if the administration rescinds the waiver that gives California the freedom to pursue tougher standards on automotive emissions.

California still has a way to go to meet its climate goals. It will have to tackle the transportation sector, its single-largest source of emissions, and compensate for ditching nuclear power, which cuts down on carbon emissions, after its last nuclear plant closes in the next decade. Still, the electricity sector has made strides, with solar, wind, and natural gas now comprising a majority of electricity generation. (Prior to the prolonged drought, large hydropower projects accounted for a lot of generation too, at 18 percent). “Who would’ve thought [a few years ago] you’d have wind and solar so competitive with hydropower?” Picker asks.

So far, Picker’s unconventional recruiting drive has resulted in some interest from federal workers. When he went through the same exercise in front of the Department of Energy from 7 to 9 a.m. on Wednesday, one staffer even helped him pass out fliers. CPUC’s executive director texted him later that day, excited to inform him that one other federal worker found his contact information on the website and expressed interest in a job.

The verdict is still out on if this approach is the most effective solution for the state’s recruitment challenges. But after his long day on Wednesday, Picker seems to have sympathy for the federal workers in DC. “I feel bad for them,” Picker says about the Department of Energy staffers. “I noticed some folks coming in late.”