Aerial footage of coastal New Jersey after Superstorm Sandy hit in 2012.Mark C. Olsen/USAF/Zuma

This story was originally published by CityLab and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

When Superstorm Sandy struck at the end of October 2012, the fallout was widespread and remarkable.

Some of the most overt consequences were immediate: signs of crisis were shouted through a bullhorn. Homes and buildings kneeled at the foundation; trees were yanked out by their roots. Water poured into subway stations, ruining electrical and mechanical systems. Power outages washed across the coast and toward the center of the country, all the way to Michigan and Ohio. Sewage seeped into bodies of water in D.C., Maryland, Virginia, and beyond.

Other consequences were quieter at first, and grew more dire as time elapsed. Mold bloomed in housing units, particularly in affordable apartments that were battered by the storm. Flooding in Hunts Point and other commercial cores highlighted profound vulnerabilities with the potential to imperil New York City’s food system.

After infusions of federal relief funds and residents’ sweat equity, some of these scars have faded. Others still linger, alongside unresolved questions.

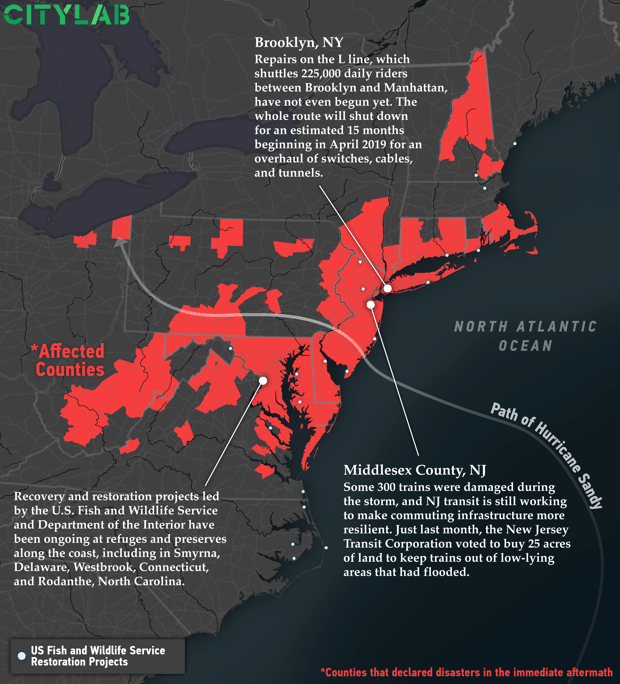

Across the affected areas, rebuilding has been an ongoing task. Below, we’ve mapped the counties that declared disasters in the immediate aftermath of the storm, and annotated a few of the efforts that are still in progress. This was a storm with years-long aftershocks.

It’s taken years to fully repair mass transit that was doused with water. Manhattan’s South Ferry subway station, inundated with 15 million gallons, just reopened this June, after renovations topping $340 million. Storm-related repairs on the embattled L line—which shuttles 225,000 daily riders back and forth between Brooklyn and Manhattan—are slated to begin in April 2019, long after flooding snarled mechanical systems.

Housing repairs have been slow going, too. Renovations to buildings managed by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) have met with significant delays. The outfit received $2.9 billion in FEMA funding, plus an additional $317 million from HUD—but in a comprehensive accounting of where the money went, DNAInfo reports that 129 buildings are still under construction, and only one has been completely repaired.

Though significant efforts have been made, programs to repair or bolster the shoreline are also incomplete. Many portions of the “Rebuild by Design” program, another enormous resiliency effort backed by a HUD grant, are still in the planning phases. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Department of the Interior are still funding recovery efforts in preserves and wildlife refuges along the coast.

The storm—and its long tail—haven’t faded from residents’ minds. As FiveThirtyEight reported last month, New York’s 311 hotline continues to field calls from locals asking about mental health services and fraud reports, all pertaining to storm recovery.

Earlier this week, in advance of the five-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy’s landfall, the FEMA photographer Liz Roll retraced her steps along the Jersey coastline, revisiting the sites of particularly wrenching photographs that became visual shorthands for the storm’s teeth and documenting the visual transformations.

Back in 2012, Roll had captured a house cleaved in two, a roller coaster swallowed and mangled by waves, and a wooden boardwalk shredded like pencil shavings. Five years later, the coaster has been rebuilt on shore, with more distance from the water’s mouth. A crane hauled the components of a new boardwalk—this time, constructed from concrete. All traces of the house had vanished: the bricks and fence and roof had been carted away, leaving a straight-on view of the water.

Doing more—and doing it well—is crucial as coastal cities like New York stare down a flood-filled future. As Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria bore down on the U.S. this summer, they resurfaced questions that Sandy provoked: How do we evacuate people from harm’s way? How do we keep transit moving, keep residents fed, and keep the lights on? How do we save people’s lives—and then look squarely at unthinkable risks, refusing to accept them as inevitable? Experts have floated a number of proposals and experiments, but none are holistic, singular solutions—or thoroughly satisfying.Meanwhile, city officials are convinced that the region is in better shape to weather future storms. “We are absolutely safer than we were when Sandy hit because of the upgrades we’ve made to emergency procedures and because of the infrastructure investments we’ve been making,” Dan Zarrilli, Senior Director of Climate Policy and Programs for the de Blasio administration, told Gothamist. “And we’ll have much more to do before we’ll ever be satisfied.” Future steps might include revisiting building and zoning codes to further emphasize storm-proofing.

Over the next few days, with our partners at Climate Desk, we’re rolling out a package of stories that take stock of what’s happened since Sandy. We’re also bringing back some previous CityLab stories about the storm and its aftermath—all to survey how cities chose to rebuild or opted not to. This is an effort to track how the region is trying to get smarter and stronger, to withstand the future storms we can’t evade. Follow along here, or on Twitter.