tommaso79/Getty

The San Francisco Bay Area did a remarkable job of rebounding from the 2008 recession: The region has since added 640,000 new jobs, and its unemployment rate hovers around 3 percent. But as you’ve probably heard, the area’s housing supply hasn’t kept up with its population growth, and neither has its public transportation. A 2017 report found that 75 percent of Bay Area commuters drive to work, and only 28 percent of new office developments are accessible by regional transit.

A state bill introduced earlier this year hopes to replenish the housing supply and encourage more drivers to ditch their cars for trains and buses—and it has sparked a fierce debate among urban planners, city leaders, and environmentalists up and down the coast. SB 827 would allow developers to bypass nearly all local zoning requirements within a half mile of a major transit stop, and build multi-family housing between four to eight stories high with no parking space requirements. (The state defines transit stops as a rail, ferry, or bus stop with two or more lines that run at least every 15 minutes.)

“California is in a deep housing crisis—threatening our state’s environment, economy, diversity, and quality of life—and needs an enormous amount of additional housing at all income levels,” bill sponsor and California Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener said in a Medium post. Wiener believes that the legislation will promote the construction of more housing; bring down housing costs by increasing supply; and create communities that emit a smaller carbon footprint by relying less on cars. Transportation makes up roughly a quarter of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions and 39 percent of California’s.

“The only way we will meet our climate and air quality goals is to build a lot more housing and to do so in urbanized areas accessible to public transportation,” Wiener wrote, referencing California’s landmark emission-reduction legislation. In September 2016, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill promising to cut greenhouse gas emissions to nearly half of the state’s 1990 levels by 2030.

There’s research to back up that SB827 will help the planet. Dense cities generally have lower emissions than sprawling suburbs. The University of California-Berkeley School of Law and Terner Center for Housing Innovation found that by putting all new residential development within three miles of a transit stop through 2030, the projected reduction in emissions would equate to removing 378,000 cars from the road, and account for almost 15 percent of what’s needed to reach the state’s emission target. Ethan Elkind, director of the Climate Change and Business Program at UC-Berkeley and UCLA Schools of Law, calls Wiener’s proposal “one of the most important climate bills in California.”

Most environmental groups agree, but one has diverged from the pack. The environmental nonprofit Sierra Club came out against the bill: “We support the goal of increasing transit-oriented development to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—but we have concerns about the approach,” it stated in a press release. The group fears that streamlining a state zoning method will remove municipalities’ authority to determine the policies right for their individual cities.

Take Los Angeles. Housing advocates there have helped pass policies to increase affordable housing—policies they worry could be hamstrung by SB 827. Measure JJJ, enacted last year, includes a stipulation that only allows developers to build more densely by transit stops if they include a certain number of low-income units. Alliance for Community Transit-Los Angeles (ACT-LA), in a February letter signed by dozens of other organizing groups, said it opposed Wiener’s bill because it would override the local measure, among other policies, allowing developers to build higher within transit zones and charge market-rate rental costs—forcing low-income families to look for housing elsewhere. To avoid such situations, ACT-LA Campaign Director Laura Raymond explains, “we organize historically excluded low-income and communities of color to be a part of planning processes. The idea to have this [legislation] coming from Sacramento is very problematic as a principle for us.”

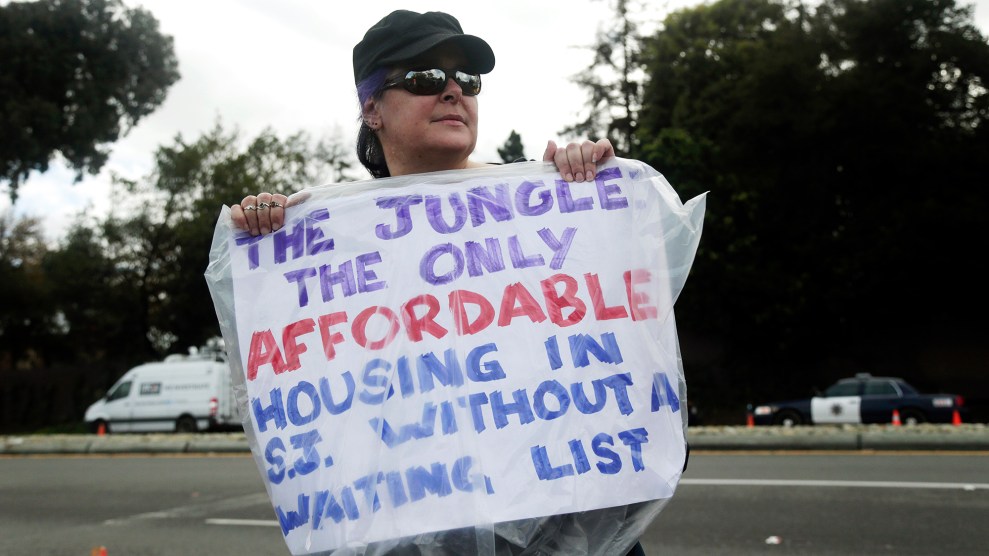

ACT-LA worries that SB 827 will propel gentrification and the displacement of low-income communities and those of color. In most cities across the state, there are weak or non-existent affordability requirements for new developments, according to Amy Schur, the campaign director for the social justice group Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE). “If 827 were to pass, it ushers in massive market rate and luxury housing development with no affordability requirements, leaving the majority of working-class folks out of the housing equation.”

“I do think the displacement concern is real in areas that are low-income now, but are already gentrifying,” Elkind says, citing San Francisco’s Mission District, a historically working-class neighborhood now brimming with artisan coffee shops. But he notes that in San Francisco, new buildings are required to make a portion of the units below market rate. The SF planning department’s preliminary analysis projected that SB 827 would result in more affordable housing units than any other existing program.

Wiener has since amended his bill to address some of the concerns about gentrification. For instance, the current version would require developers to uphold city policies like rent control, demolition requirements, and affordable housing incentives. But it wasn’t enough to garner support from Los Angeles organizing groups or the city council, which voted to unanimously oppose it this week. “The bill takes a chainsaw approach to the patient, instead of a scalpel,” said LA City Councilmember Joe Buscaino at the meeting. “It would lead to massive displacement,” Councilmember David Ryu said.

Elkind sees displacement as an inevitable product of the state’s housing shortage. “We don’t have a lot of great options given how badly we’ve under-produced housing relative to population and job growth in the state,” he says. Without taking some sort of action, “this problem is just going to continue to get worse and worse.”

Clarification: This story has been revised to better reflect the nature of the amendments to SB 827.