Imgorthand/Getty

Americans are increasingly putting their money where their mouth is—and eating out more than ever before. Back in 1970, Americans only spent 26 percent of all their food expenses at restaurants or cafeterias. In 2014, that number rose to 44 percent. Today, about half of the country reportedly “hates” cooking and more than half of total US food dollars is spent at restaurants, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Now, a new study published Wednesday in the journal Environment International suggests that Americans’ habit of eating out could be costing us more than a portion of our paychecks. It turns out, eating outside the home—at restaurants, fast-food joints, and cafeterias, including delivery and take-out—is correlated with higher body levels of phthalates, a ubiquitous class of chemicals linked to all sorts of ailments including reduced semen quality, diabetes, lower IQ, and cancer.

Phthalates aren’t intentional food additives; they’re a group of chemicals mixed with plastics to make them more flexible, but they can also leach into our food, research suggests, through contact with products like plastic containers, food-handling gloves, and processing equipment.

In this study, researchers from UC-Berkeley, UC-San Francisco, and the George Washington University analyzed urine sample data for more than 10,000 Americans taken between 2005 and 2014 from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a government-backed, health survey performed every two years. Each of the participants reported what they ate the day before and where they got it. In all, about two-thirds of the respondents had eaten out at least once in the prior day.

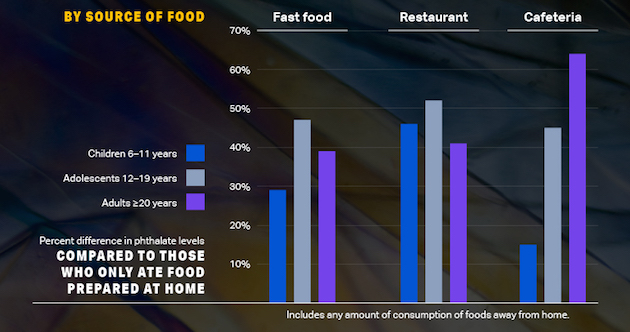

“We found that people who eat out more at full-service restaurants, cafeterias, and fast-food restaurants have nearly 35 percent higher phthalate exposures than people who bought their food from a grocery store, and are presumably eating at home,” Ami Zota, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health at the George Washington University and senior author on the study, tells Mother Jones.

Percent difference in phthalate levels compared to those who only ate food prepared at home.

Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University

The researchers also found that high fast-food consuming adolescents had phthalate levels 55 percent higher than their home-cooking counterparts. And across all ages, the difference of eating at home and eating out is particularly stark with sandwiches containing meat; people who ate restaurant-made meat sandwiches (including hamburgers) saw phthalate levels more than 30 percent higher than the people who ate homemade meat sandwiches. The group saw similar results for people who ate restaurant pizzas and fried potatoes.

While the authors aren’t able to specifically explain why cheeseburgers, for example, result in higher phthalate levels, the authors suggest that the way consumers cook foods (frying vs. grilling, for example) may play a role, as well as differences in plastic exposure.

“Our findings suggest that eating fresh, less processed foods at home can potentially reduce biologically-relevant phthalate levels in your body, and that’s something you could do tomorrow,” Julia Varshavsky, a postdoctoral scholar at UC-Berkeley’s School of Public Health and the lead author on the study, tells Mother Jones.

The ideal solution, though, isn’t really to keep people out of restaurants, says Varshavsky. “We all love going out to eat, clearly, by the statistics. I do too,” she says. “So yes, eating at home is a good strategy, but at the same time, there’s a bigger problem, and the challenge is really, how to solve that problem: how can we keep phthalates from contaminating the food supply in the first place?”

“This study points to the need for more systemic changes through policy and market-based solutions. We need both,” says Zota. “There’s some things that individuals can do, but phthalate contamination at the food supply represents a larger public health problem.”

Phthalates are used in hundreds of common products, and constant exposure to this class of chemicals may just be part of modern living. “Phthalate exposure is widespread,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and we don’t yet have a full understanding of the effect of these chemicals on human health.

“It is very hard to control exposures to these kinds of chemicals in your daily life,” Sheela Sathyanarayana, an associate professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Washington and chair for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee, who is not associated with the study, tells Mother Jones in an email. And, as Sathyanarayana points out, this study “supports eating at home, which is not always feasible for the average family or for children.”

The somewhat good news is that phthalates only last in the body for about a day, unlike other contaminants that can get into our food. (For example, as we’ve written about before, a chemical called PFOA takes years to leave the body.) The issue is really their ubiquity and the near-constant exposure many people have to phthalates. But, in theory, if changes were made to “remove phthalates from the food supply tomorrow,” says Varshavsky, we’d see a near-immediate drop in phthalates in people’s bodies.

If we remove the source of exposure, phthalates should go away, which is not what you can say about many chemicals out there,” she concludes. Until then, maybe those leftovers don’t look so bad.