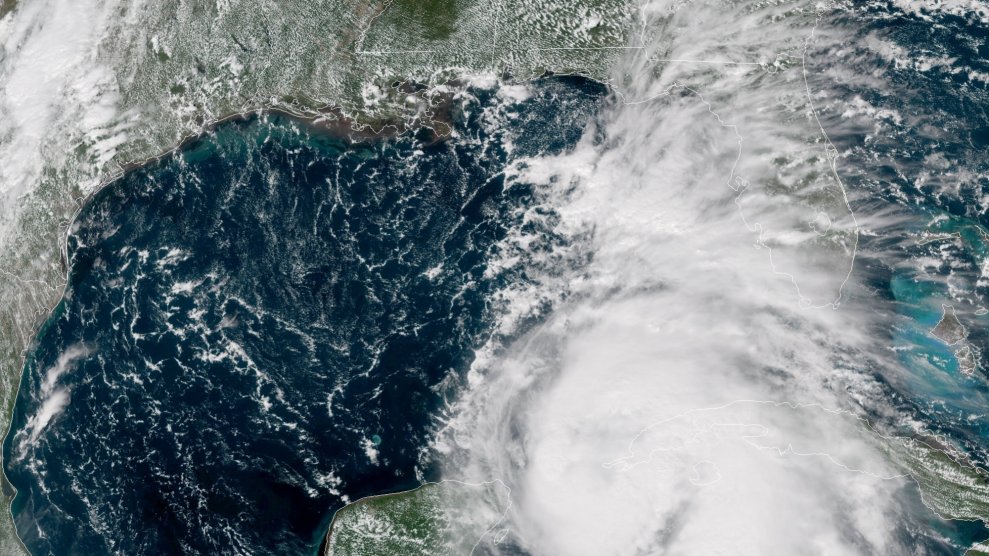

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Hurricane Michael—with its 145 mph winds—has made landfall and it’s set to become the strongest hurricane on record to hit the Florida Panhandle. Coming on the heels of Florence, which inundated the Carolinas with record rainfall and led to at least 17 deaths, Michael is especially dangerous because of the threat of catastrophic storm surges.

Storm surge refers to the rise in sea level above the normal tide level. The one that Michael threatens could be up to 14 feet in some communities and could potentially devastate property throughout the region. Hurricane Sandy, which brought at most 9 feet of storm surge, was responsible for $19 billion in damage across the New York area, and Michael’s size and unique path could ensure it packs an even more powerful punch. “Unfortunately, Hurricane Michael is a hurricane of the worst kind,” FEMA Administrator William “Brock” Long said Wednesday at a news briefing.

A number of factors make Michael’s storm surge such a threat. For one thing, the hurricane is huge and very strong. After it makes landfall, the National Hurricane Center predicts that it will be a Category 4 storm with tropical-storm-force winds extending up to 175 miles from its center. If Michael remains at that level, it will be the most powerful October hurricane since Hazel hit the Carolinas in 1954. The Weather Channel has an explainer to show what the storm surge could mean:

Just after noon on Wednesday, the storm tide on the shore of Apalachicola Bay was more than 6 inches above high tide, the forecasting service Weather Underground reported.

“Winds blow in a spiral direction and pile up water right near the center of the storm,” says Jeff Masters, the co-founder of Weather Underground. “When the water gets all piled up there in the eye, it has nowhere to go. As the storm moves ashore, it takes that bulge of water with it.”

In a year of several extreme weather events—even Siberia recorded historically warm temperatures in July— Michael is still unusual. It will only be the tenth major hurricane to make landfall in the Florida Panhandle since 1851 and one of the few at this time of year, when colder seas make tropical storm formation more unlikely. Instead of finding obstacles to expansion, Michael is sweeping up water from an abnormally warm Gulf of Mexico. “Even though it is early October, no cold fronts have yet chilled the waters near the central Gulf Coast, so very warm surface waters are in place to support Michael right up to landfall,” Masters wrote in a blog post this week.

While the Panhandle will take the brunt of Michael’s impact, the already-waterlogged Carolinas won’t be immune from remnants of the storm. Michael is arriving during a time of extraordinarily high tide, known as the “King Tides,” which could produce another storm surge along the Atlantic Coast, where residents are still recovering from Hurricane Florence. During these tides, which occur when the Sun and Moon are aligned with the Earth, a weakened Michael may drive up flooding totals.

Both North and South Carolina declared states of emergency on Wednesday in preparation for the storm and Long, the FEMA administrator, urged Georgia residents to “wake up and pay attention.” Michael could be the worst storm, he said, the state has seen in “many, many decades—and maybe ever.”