Residents evacuate as the Easy Fire approaches Simi Valley, California on October 30.David McNew/Getty

California’s Kincade and Getty fires—burning across the state’s northern wine region and Los Angeles’ Santa Monica Mountains—have consumed almost 80,000 acres of land and prompted more than 200,000 evacuations. The Kincade Fire alone threatens 90,000 structures. By Wednesday morning both fires were almost 20 percent contained, but severe winds could reverse progress firefighters have made. Meanwhile, almost a dozen other large fires are burning across the state.

Add to their many tragic consequences—the loss of life and property, the dislocation, the strain on resources—the fact that wildfires release large amounts of pollution into the atmosphere. A study published last week by the National Bureau of Economic Research from air pollution scientists at Carnegie Mellon University revealed that for the first time since 2009, air quality nationwide had plummeted, and nowhere fared worse than the west. Between 2016 and 2018, the levels of fine particulate matter—inhalable specks of liquids and solids that make up air pollution—increased by 11.5 percent. The result? Vulnerable people in these areas experience a greater number of heart attacks, strokes, and worsening of pulmonary conditions such as emphysema and asthma.

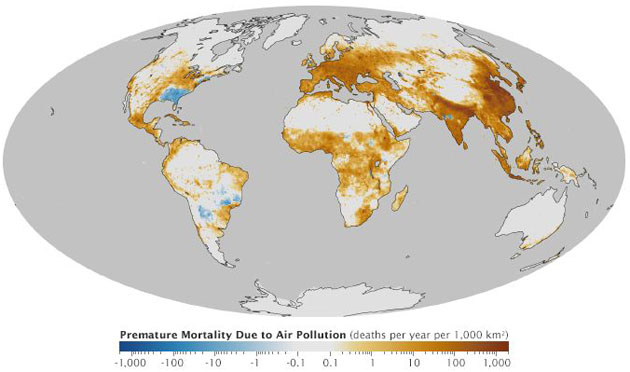

Researchers also found that the increase in air pollution since 2016 has caused almost 10,000 premature deaths across the country, with more than 40 percent of them in California alone. Karen Clay, an economics and public policy professor at Carnegie Mellon and one of the study’s authors, speculates that the overall increase in California’s air pollution comes from myriad sources, including increased economic activity and a decline in EPA regulation enforcement. Wildfires are one important factor in the uptick, but, she says, their specific impact is difficult to measure with any accuracy.

One way to do so, though, is look at health data of people who have been exposed to those fires. According to Dr. Nicholas Kenyon, a professor and pulmonologist at UC Davis, the school’s Environmental Health Sciences Center has been conducting surveys of Californians in areas affected by wildfires. The research hasn’t been published yet, but the numbers he’s seen are troubling —especially when it comes to preexisting conditions like asthma.

“Fifty percent of them had worsening asthma symptoms,” he says. “These were folks who were from a few miles to many miles away [from fire events].”

The mortality rates specifically linked to air pollution can be difficult to measure, but a particularly dramatic event, a wildfire for instance, that occurs during a restricted time period could provide useful data. While analyzing stats on air pollution rates and resulting deaths, Clay and her colleagues decided to isolate specific months to spot trends. When findings from November 2018, the month of California’s Camp and Woolsey fires, were separated from the data overall, they found that over a thousand people died from air pollution-related ailments, in comparison to the previous months when the average mortality rate was a fraction of that. After eliminating all other possible factors, the researchers concluded the fires were the only variable that could explain the upturn.

“To cause that kind of effect,” Clay says, “some polluter would suddenly take off their emission controls, but only in November of 2018.”

Officially, 88 deaths have been attributed to the Camp and Woolsey fires, but these were the people who were directly in harm’s way. But then researchers examined the effects of the pollution the fires released into the atmosphere, and found that it lead to the premature deaths of up to 1400 more people. This does not include how the pollution has affected countless others whose preexisting conditions were intensified by the bad air.

“There’s a huge quality of life component for people who didn’t die,” she says. “The kid down the block who gets asthma and has another asthma attack because the air quality is really bad. The person who has to be on oxygen because of air quality issues.”

Researchers noticed that during the Camp Fire, many who suffer from respiratory ailments made more trips to the pharmacy rather than the hospital. Anthony Wexler, the director of the Air Quality Research Center at UC Davis, said that the 2018 wildfires, which burned about 250,000 acres and displaced almost 300,000 people, caused “probably the worst air pollution in the world at the time,” but didn’t lead to an increase in ER visits to UC Davis Medical Center.

“People who have some preexisting condition,” Wexler says. “Those people are very much susceptible to this kind of stuff, and it could push them over the edge. Albuterol use went up. People who have asthma used more inhalants in order to get past this terrible wildfire smoke.”

And not all wildfire smoke is equal. In 2018, the same year of the Camp and Woosley fires, the Mendocino Fire burned more than 450,000 acres of national forest land and was the biggest fire in California history. But the effects of this fire’s pollution weren’t visible in the mortality rates of the Carnegie Mellon study. Wexler suggests that the worst fires aren’t the biggest ones, but the ones that burn closest to people—and their man-made materials.

“Houses have terrible chemicals in the construction materials and whatever they got lying around,” Wexler says. “That stuff probably is much worse for you than regular old wildfire smoke.”