Colorado River near Moab, Utah.Jon Fuller/VW Pics/ZUMA

This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Fears, concerns, and legal challenges over a proposed oil train route along the Colorado River were finally addressed in federal court last week. Until then, plans for the Uinta Basin Railway project, which would ferry vast amounts of crude oil from northeast Utah eastward alongside the Colorado River, sailed through federal agencies tasked with approving large transportation projects. But then the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, DC, successfully challenged the project’s environmental impact assessments, siding with the railway’s opponents and striking a blow against what would have been the largest petroleum corridor in the United States.

A coalition of seven fossil fuel-producing counties in Utah allied with the investment bank Drexel Hamilton sought to quadruple oil production in Utah’s Uinta Basin, 12,000 square miles of desert floor crowned by mountains and currently accessible only by truck. The Ute Indian Tribe also has a stake in the project, as some of the oil would be extracted from Uintah and Ouray Reservation land. The $2 billion plan called for 88 miles of new track through the Ashley National Forest, connecting to an existing Union Pacific line into Colorado, which snakes another 150 miles along the Colorado River and into downtown Denver.

The crude would travel south from Denver toward the constellation of city-scale refineries on the Gulf Coast commonly referred to as “Cancer Alley.” Before the trains—up to five of them a day, each about two miles long—reached their final destination, a federal analysis predicted that, every other year, one of them was likely to experience an accident by the Colorado River.

The lawsuit against the project was backed by multiple Colorado communities along the proposed route as well as the Center for Biological Diversity, a nonprofit conservation group. They raised a number of issues, but the main one attacked the way that environmental impacts were studied in the federal analysis of the rail project. The environmental impact statement, which the plan’s approval depends on, almost exclusively considered risks posed to Utah and a small segment of new track exiting the Uinta Basin. The rest of the route, including the part skirting the Colorado River and Colorado mountain towns, was largely omitted from the study.

That omission was a key factor in the court’s decision to effectively reverse the approval previously granted by the Surface Transportation Board, which arbitrates disputes on transportation projects. According to the court ruling, the environmental impact statement failed to “take a hard look at wildfire risk as well as impact on water resources.” The court also cited a lack of consideration for endangered fish in the Colorado River as well as the health of the Texas and Louisiana residents who would bear the brunt of increased air pollution near oil refineries.

By ignoring those concerns, the project ran afoul of the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires all federal agencies, including the Surface Transportation Board, to fully assess the environmental impacts of projects they oversee.

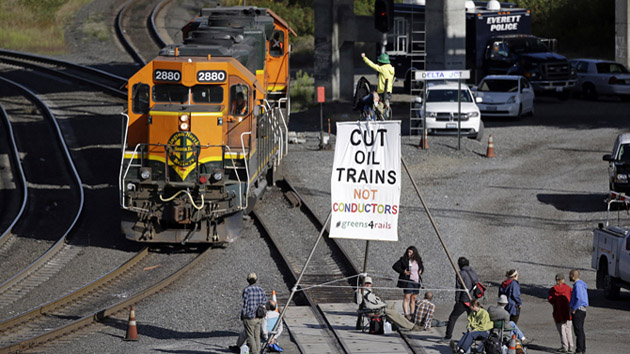

Railway opponents celebrated the decision as a hard-fought victory. For months, Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet and Rep. Joe Neguse, District 2, both Democrats, criticized the oil train, writing letters to Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg and other federal officials in a position to intervene on the project. In April, they even staged a press event in Glenwood Canyon by the Colorado River to raise awareness about the risks posed by the oil trains.

“This ruling is excellent news,” Bennet and Neguse said in a press release following the court decision. “The approval process for the Uinta Basin Railway Project has been gravely insufficient, and did not properly account for the project’s full risks to Colorado’s communities.”

Bennet and Neguse added that “an oil train derailment in the headwaters of the Colorado River would be catastrophic—not only to Colorado but the 40 million Americans who rely on it.”

Equally vindicated were the countless staff and attorneys at the Center for Biological Diversity involved in the now five-year struggle. The group, which lodged the earliest lawsuits against the project, was dealt an early defeat when it failed to persuade the U.S. Forest Service to deny preliminary approval for the rail segment through the Ashley National Forest in 2021.

“This is an enormous victory for our shared climate, the Colorado River, and the communities that rely on it for clean water, abundant fish, and recreation,” said Deeda Seed, a senior campaigner with the nonprofit. In the meantime, the Surface Transportation Board and the coalition supporting the oil train project “ has a lot of work to do before this can be considered again,” Seed told High Country News on a call. “If they want to go ahead with this, they need to do the research about downline impacts.”