A West Indian manatee surfaces for air in Tampa, Florida.Douglas R. Clifford/Tampa Bay Times/Zuma

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The second line started at four, but it was five o’clock somewhere.

Hundreds of people gathered here on a September Sunday—their Hawaiian shirts and flip-flops brightening the city streets—to participate in a walking parade in remembrance of Jimmy Buffett, who spent much of his childhood in this Gulf Coast city. Buffett, a poet of paradise, died Sept. 1 at age 76.

Though he may be more commonly associated with Florida, the late musician and environmental philanthropist was born in Pascagoula, Mississippi, and was raised in Mobile. In addition to his musical legacy, Buffett was a champion for environmental causes, co-founding the Save the Manatee Club with then Florida Gov. Bob Graham.

Like Buffett, the West Indian manatees the musician worked to protect are more commonly associated with Florida, but the threatened species also calls Alabama home.

Increasingly, however, scientists are concerned that factors including climate change are complicating life for the large marine mammals, changing their migratory behavior in ways that may be causing them harm.

Micha Reed was among the Parrotheads in Mobile for the memorial march. She’d heard about Buffett’s environmental work, particularly that involving the manatees.

Micha Reed shows off her Buffett concert poster from 1982.

Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News

“I think it was a great thing,” she said of the Save the Manatee Club. Her southern twang hung thick in the late summer humidity as she spoke outside Moe’s BBQ after the second line had come to a close.

But discussing climate change and its political and environmental implications wasn’t something Reed or others seemed eager to do this Mobile Sunday. “Sometimes I just think we focus on the wrong things,” Reed said as the sun began to set, declining to be drawn out on the subject.

Bama’s scars tell the story.

Often, scars become a part of a manatee’s identity—a way for environmentalists to identify one animal from another. That’s the case for Bama, the first manatee tagged by staff with the Dauphin Island Sea Lab’s Manatee Sighting Network in Mobile Bay in 2009.

Bama swims in Florida waters during much of the year.

Patricia Wilbur/Florida Department of Environmental Protection

“Bama’s key identifying feature is a scar on the left side of her back, near the middle of her body, which was caused by a boat propeller,” according to the Save the Manatee Club.

Using the scars for identification purposes is making lemonade from lemons, said Elizabeth Hieb, manager of the Manatee Sighting Network, who called the healed wounds “human-caused fingerprints.”

“A lot of these manatees have interactions with boats and have scars from propellers that we can use to identify individual manatees, much like a fingerprint,” she said.

Being able to identify one manatee from another has become increasingly important as scientists like Hieb grapple with better understanding the ways in which climate change is impacting the species, both directly and indirectly.

West Indian manatees are large marine mammals, like dolphin and whales, and are native to the Gulf Coast. Typically, manatees spend their winter months in more southern areas, often in Florida, and migrate north to areas including Alabama during the summer.

Over time, however, scientists like Hieb believe the number of manatees in the area has increased and that manatees are lingering in the area longer in the year—a change potentially caused by climate change that could have serious implications. “As far as we know, manatees can’t withstand a full winter here, so they have to migrate back to those warmer sites,” Hieb said.

Scientists are trying to understand the dynamic in more detail, Hieb said, but it seems that the warmer surface water temperatures in places like Alabama may be lulling manatees into a false sense of security that is quickly stripped away when temperatures begin to dip in November and December. Hieb pointed out that climate change can also lead to extreme cold events, which could worsen the impact of increasing average temperatures on manatees’ migratory patterns.

“It could be the perfect storm of it being warm enough for them to come, but then during the coldest parts of the winter, we’re still getting this extreme cold,” Hieb explained.

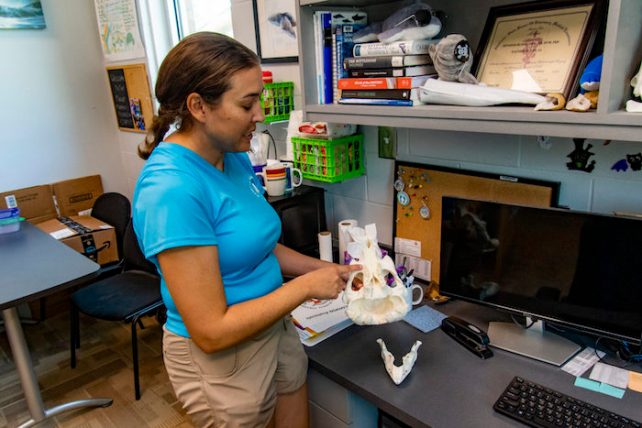

Elizabeth Hieb describes the manatee’s anatomy as she holds a skull inside Dauphin Island Sea Lab’s marine mammal research facility

Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News

The leading cause of death for manatees in Alabama in recent years has been cold stress, according to Hieb.

Manatees, like humans, can suffer from frostbite lesions, especially on their extremities. Manatees will eventually die in waters below 68 degrees Fahrenheit, Hieb said.

Water temperatures in the Mobile area reach lows of 68 degrees as early as October, according to federal meteorological records.

Hieb said the Manatee Sighting Network has logged more live manatee sightings in the winter in recents years, likely because of higher and higher water temperatures later in the year. But once winter comes, the chance of a manatee surviving in Alabama drops drastically. “Ultimately, most of these manatees don’t make it,” she said.

Migratory changes aren’t the only human-caused impacts on manatee life on the Gulf Coast, either.

Next to cold stress, boat propeller strikes are the most common cause of injury and death to manatees in the area.

And because manatees are becoming more common in the area for a longer period of time, the number of interactions between humans and manatees will likely go up, too.

In 2022, sea lab officials responded when a local fisherman reported a manatee in distress in the Theodore Industrial Canal in Mobile County. A rescue was undertaken by officials, but the manatee died during transport. A necropsy concluded that the manatee suffered from cold stress and heart disease and that the animal’s esophagus was blocked by plastic debris.

“While cold stress alone could have been enough to cause the manatee’s death, in this case, there was more to the story. The manatee also had chronic heart failure that led to severe lung disease,” said Dr. Jennifer Bloodgood, a veterinarian with the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. “This condition would have made it very difficult for the manatee to breathe and may have been exacerbated by the cold water temperatures. In addition, a plastic bag was found blocking the animal’s esophagus and likely prevented the animal from being able to swallow food.”

Dauphin Island, Alabama, is the state’s only barrier island, providing protection for much of the Alabama’s coastal natural resources.

Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News

Hieb said it’s important for the public to be aware of the risks humans pose to manatees. “It’s illegal to do anything that changes the animal’s behavior,” Hieb said.

Most people understand that injuring or killing a manatee is outlawed, but something as simple as feeding one of the marine mammals is also prohibited—and for good reason. “Let’s say it’s late November, and you’re feeding a manatee,” she said. “They may not leave when they’re supposed to, because there’s a buffet for them to eat.”

That seemingly innocuous decision—to feed the manatee—could then cost the animal its life.

Ultimately, Hieb said efforts like the Manatee Sighting Network and Save the Manatee Club are important because they help both scientists and the public to better understand the challenges facing the threatened species. And all evidence on that front point to one important reality, Hieb said: “Humans are the number one threat to manatees.”

As news of Jimmy Buffett’s death spread earlier this month, Alabama’s governor weighed in on the state’s loss.

“Like many Alabamians, I am saddened to learn of Jimmy Buffett’s passing,” Gov. Kay Ivey posted on X, the social media platform previously called Twitter. “Truly, the stars fell on Alabama’s shores with his music, and there will never be another quite like him who can capture the spirit of our Gulf Coast. Rest easy, Jimmy.”

Buffett has deep roots in the Yellowhammer State. The country icon was raised in Mobile, Alabama, and graduated from what is now McGill-Toolen Catholic High School.

“I was still an altar boy ‘til I was 17 years old,” Buffett once said. “I didn’t get into a lot of trouble, and I was just kind of bouncing along… What I fall back to is my Jesuit years, my parochial school years and my summers on the Gulf Coast.”

Through the years, crowds flocked to see Buffett perform at concerts across the state. In 2015, Buffett—considered a native son by many despite his birthplace—sang to a crowd of 10,000 in Orange Beach. “If I were a religious person, I would say that constitutes the redneck Riviera rapture,” he told those gathered.

Before Buffett’s death, the southerner’s environmental activism had long been part of his identity. In 1987, for example, Buffett testified before Congress in support of reauthorizing the Endangered Species Act.

During the hearing, Buffett argued that the act had specifically helped protect the West Indian manatee. Sen. Max Baucus asked Buffett to tell him more about the animal. “We don’t have many in Montana,” Baucus said.

“They hang out in bars,” Buffett replied.

Years earlier, in 1981, Buffett and Gov. Graham founded Save the Manatees after a backstage conversation about the endangered species. In the years since, the organization has worked to increase education, regulations and enforcement to reduce manatee deaths caused by humans. Buffett also was part of the board of directors for the Everglades Foundation, a science and advocacy organization.

Parrotheads crowd Mobile’s streets to celebrate the life of Jimmy Buffett.

Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News

Lined up alongside other Parrotheads, Micha Reed said she thinks Buffett’s work to save the manatees was admirable.

Reed said Buffett has always been an important part of her life in Mobile. “Every girl has a rock star,” Reed said, a smile on her face. “For the girls a little older than me, it was Elvis. For me, it was Jimmy Buffett.”

Buffett’s style of music drew her in, Reed said. Just the day before, she explained, she drove down the long bridge to Dauphin Island, Alabama’s de facto Margaritaville.

“I listened to Jimmy Buffett all the way there and all the way back,” she said.

As Reed spoke on Sunday, a man strumming a guitar began to sing Margaritaville nearby. She smiled again.

“When my husband took me to my junior prom, he borrowed his sister’s car, and it had an eight-track player in it,” she said. “After the prom, he took me over there to the overlook in Spanish Fort, and we listened to ‘Stars Fell on Alabama.’”

Reed said it was important for her to come out to the second line to remember Buffett. “I just had to be here,” Reed said. “It’s like going to his funeral, but it’s a party at the same time.”

Earlier in the evening, Reed said she’d spoken with a stranger who’d been to the same Jimmy Buffett concert in Mobile that she’d attended more than four decades ago. Reed had brought a poster from the concert to the second line, decorated with island leis at its top. Reed said after they’d talked about the concert, the stranger hugged her neck.

“It’s like how you see old family and friends at a funeral,” she said. “We didn’t know each other at all, but we have that in common.”

Asked about Buffett’s environmental work, Reed said she agrees that protecting the Earth is an important cause. “I think God created the Earth, and it’s our responsibility to take care of it,” she said. “I’m trying to do my part. We like to go kayaking, and we never leave trash. You bring it in, you take it out.”

But sometimes, Reed said, celebrities go “too far” in their support for certain causes. “I think it’s okay to have their concern,” Reed said. “Like the manatee thing—I think that was a great thing. But I think when they start to tell us who we ought to vote for, that crosses a line. We love them for what they do and not all their politics.”

In his time, Jimmy Buffett didn’t shy away from taking political sides, which he argued was necessary in order to protect threatened species like the manatee. During the 2018 primary campaign for Florida governor, Buffett held a concert in support of Gwen Graham, Bob Graham’s daughter and a Democratic candidate for the state’s highest office.

“It’s pretty simple, we live in paradise, and paradise is in peril,” Buffett said at the event. “We need to have a little more attention about the place where we grew up, and where our children should grow up. It’s not that hard. It really isn’t.”

For some, though, climate change and the political baggage that come with it can be a hard subject to broach. On Sunday, Micha Reed wouldn’t say whether she believed climate change is primarily caused by humans. When asked about the subject, she took a moment to reply. Then she chose her words carefully. “I think we focus on the wrong things,” she finally said.

She paused again. “But I’m afraid to go there.”