Pinch the skin on the top of your hand and then let go. It should drop back into place, a nursing student told me as we stood in a dim Sunday School room at Wesley United Methodist Church in South Phoenix last summer. If, however, the skin stays up, “tenting” as nurses say when they’re testing skin turgor, then you’re in some trouble—seriously dehydrated, headed toward the kinds of physical heat response that would kill 425 people in Maricopa County before the year was out.

That day at the Wesley UMC Cooling Center, all sorts of people were trying to keep the death count from rising higher. The nursing students putting in their community health hours, a handful of senior church ladies, the pastor herself, and people who lived on the streets—they were all moving in and out of two cinderblock rooms that the church’s beleaguered rooftop heat pump was able to keep down to about 80 degrees. Wesley was one of nearly 100 designated sites in Phoenix open to the public for daytime refuge during heat season. City-funded spaces like libraries or rec centers had certain restrictions—no bathing, no lying down to sleep, no pets—but self-funded sites like Wesley had the freedom to create their own rules and culture.

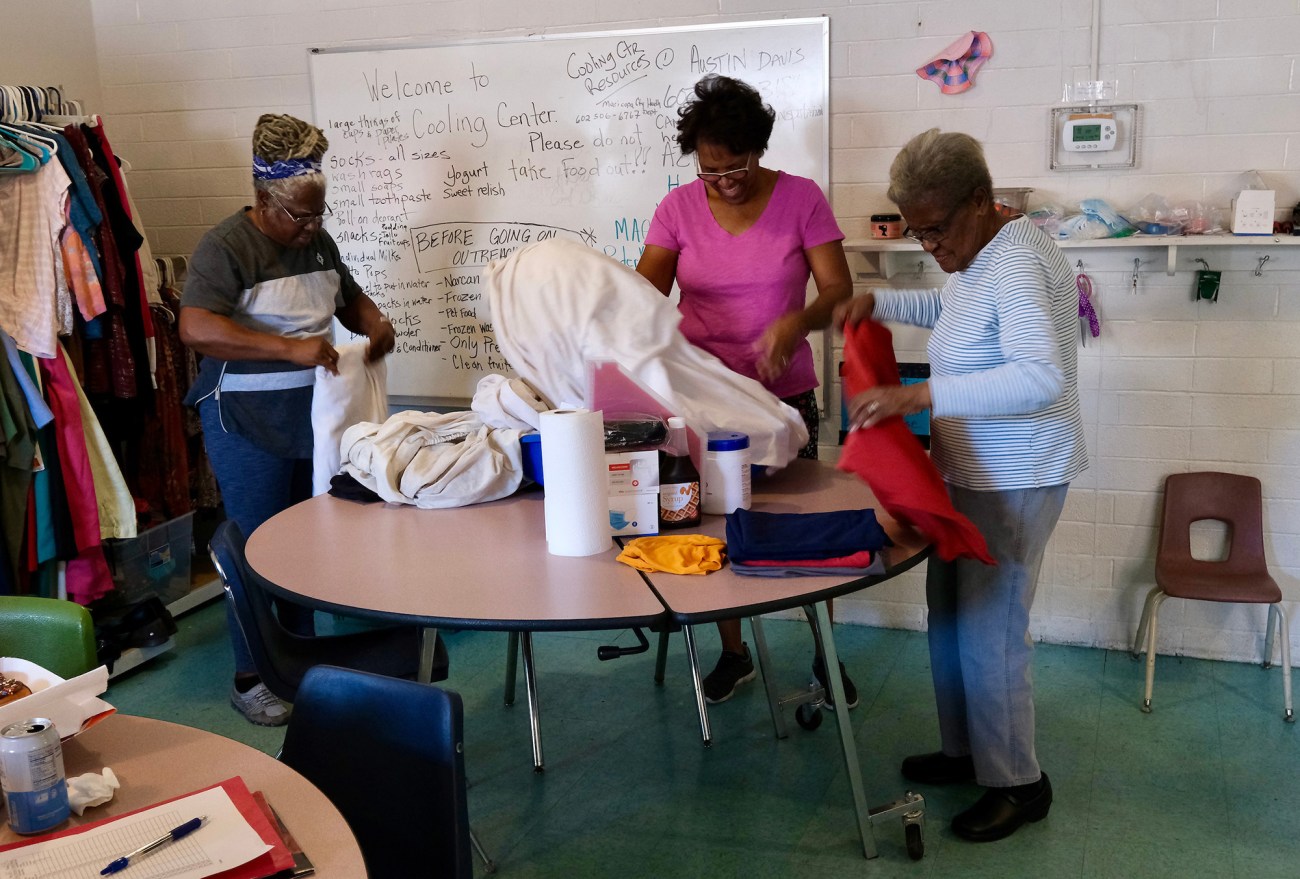

“Welcome, welcome!” said Corine Hill-Hicks whenever the door swung open. She and Lucy McCray, both retired elementary school teachers who still addressed each other as “Mrs. Hill-Hicks” and “Mrs. McCray,” were the intake crew, known by the center’s regulars as “The Ladies,” a.k.a. “The Golden Brown Girls.” They’d both endured recent tragedies—Mrs. Hill-Hicks, a vibrantly dressed and apple-cheeked woman of 64, suffered two strokes that left her using a rolling walker. Mrs. McCray, tiny, prim, and 22 years older, had lost Bobby, her husband of more than 50 years. They drove themselves over to Wesley every weekday to volunteer-host the center’s heat respite rooms, and somehow, they made it fun.

Volunteer Corine Hill-Hicks, a retired South Phoenix school teacher, is well known in the neighborhood as the center’s welcomer.

One day, Mrs. Hill-Hicks was an hour late, and Mrs. McCray kept popping up from the welcome table to look out the window for her. “Oh I missed you, girl!” Mrs. McCray cried out when Mrs. Hill-Hicks finally wheeled through the door.

“Now, I called and told you they were putting in my AC today,” Mrs. Hill-Hicks said, with a little eye roll.

“You see when you’re 86 what you remember!” Mrs. McCray snapped back, and they both cracked up.

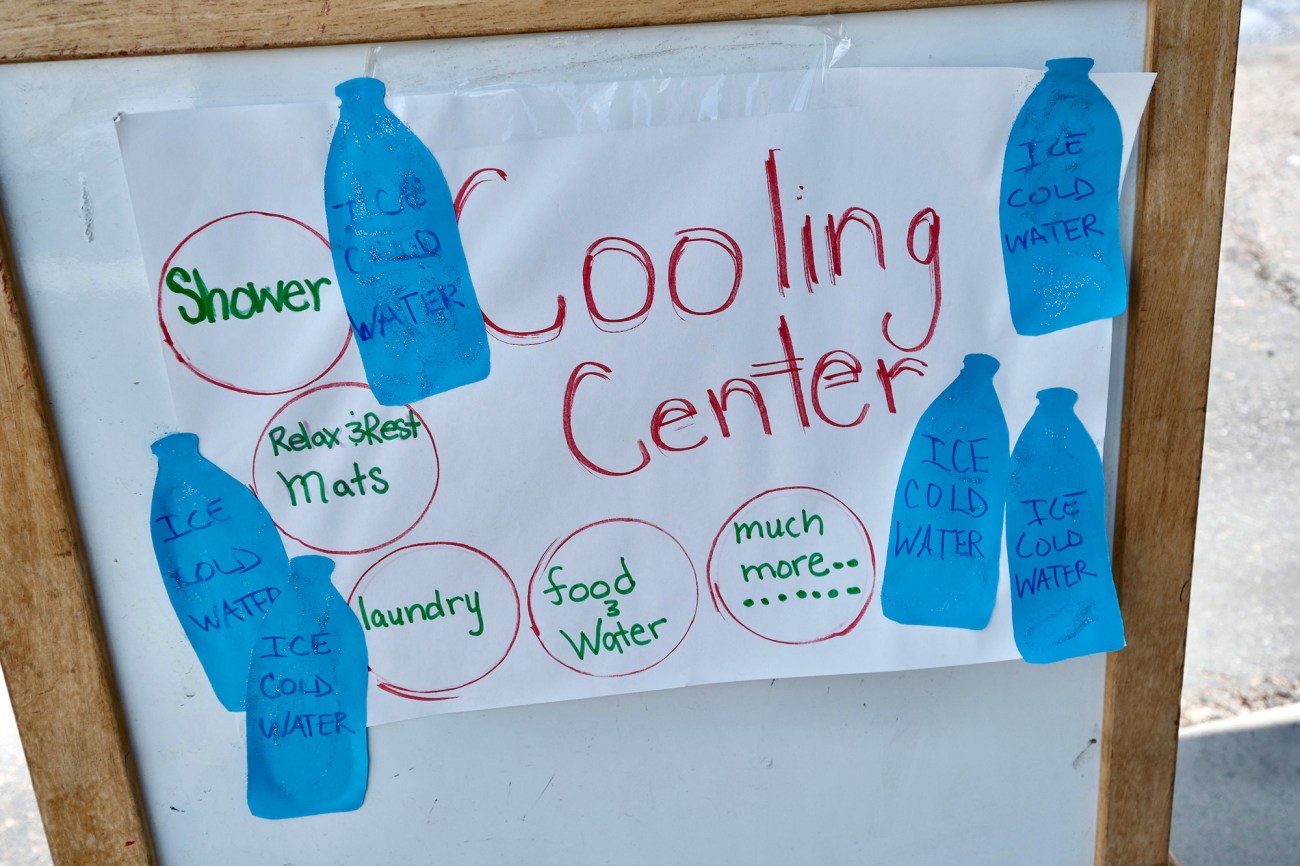

By 2022, plenty of cooling centers in Maricopa County’s sprawling Heat Relief Network offered life-saving basics—air-conditioned rooms and cold water. But the pastor and parishioners of Wesley, a historically Black church in a historically vulnerable neighborhood, understood that the needs around them went far beyond AC and a freezie pop. People were struggling with homelessness, hunger, and addiction—all things that extreme heat made so much worse. Though the church was small, drawing only about 30 people to Sunday services, its members decided last year to help in any way they could on their limited, offering-plate budget. They asked neighbors, many of whom lived in Section 8 housing, and local nonprofits to donate snacks, water, hygiene kits, and time. The church had a washer and dryer, so they decided to offer laundry services. Aspen University agreed to send the nursing students. On June 1, they set up a “Cooling Center” sandwich board sign out front on Southern Avenue, and soon, 15 to 25 unsheltered, exhausted, and often addicted visitors were showing up each day, frequently with dogs.

Andrew was one of the early regulars. Unhoused, hooked on “the blues”—fentanyl pills that, when smoked, barely deliver a high but prevent withdrawal—and down to the clothes on his back, Andrew came by daily, so the ladies had the chance to get to know him. He was a quiet guy, 33, with a remarkable resemblance to the late rapper Mac Miller—same wide eyes and buzz cut, even a similar neck tattoo. He got addicted to opioids 20 years earlier in California, he told them, right after his mother died and a teenage friend offered him OxyContin pills to help manage the tsunami of grief.

An old easel is repurposed as curbside advertising for heat relief services provided no-charge to neighbors.

Once he landed in Phoenix, the combination of heat so strong it screwed up his digestive tract and the dehydrating effects of fentanyl zapped him—he hadn’t been able to secure work or a place to live. The cooling center offered him a nonjudgmental spot to regroup each day, hydrate, have a couple cans of tuna, wash up, nap on a yoga mat, and check in with the people he now called family.

“Andrew, can you see if the shower’s hooked up?” Mrs. Hill-Hicks asked at opening time one blistering day last August. (One of the nursing students, an army vet, had rigged an outdoor shower-platform with a garden hose.)

Andrew grinned. “Probably not.”

“Oh, everybody’s got a joke today!” Mrs. Hill-Hicks said.

But Andrew touched her arm, already on his way out the door to see about the hose.

“Anything for you, my darlin’,” he said.

Phoenix is stupid hot, but a lot of people came for that. It can be hard to understand why, in a time of homicidal heat domes, they still come. Journalist David Knowles called the hottest major city in America “a dystopian dare.” But the winters are still real nice, and the place has enchantments—wildly shaped buttes and a blossoming array of Sonoran-adapted plants. Palo Verde trees line streets with grass-green trunks, a symbol of the tree’s ability to draw back its life force and keep photosynthesizing in drought years. Southwest-hip boutiques sell small bundles of creosote, an herby shrub people hang in their showers because to many Arizonans, it’s a comforting scent—exactly what the desert smells like in summer rain.

The city holds an economic attraction too. Newcomers find a cost of living cheaper than the coasts, and a heap of decent-paying jobs—Banner Health and Wells Fargo each have thousands of employees there and tech companies like Intel, PayPal, and GoDaddy have invested heavily, as well. The vibe is aspirational.

Phoenicians aren’t in denial that our greenhouse gas-blanketed world will mean more extreme weather conditions, though this year’s unconscionable string of 31 days at 110-plus degrees and no-show monsoon season landed, painfully, on the early side of predictions. City leaders have debated and tested various climate adaptations for years, as have “cooling technology” companies, nonprofits, and a roster of sustainability researchers at Arizona State University. In a way, the city is a frontline laboratory measuring just how much lethal heat humans can take, and what might help them acclimatize to survive more.

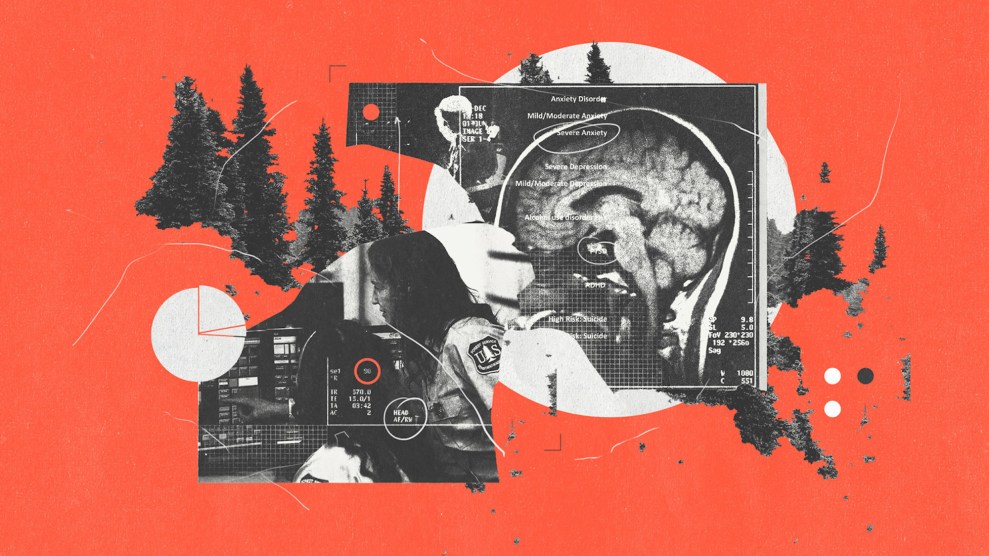

Extreme temperatures in South Phoenix have contributed to a steep increase in heat-related deaths this year, especially among the unhoused.

In the northern Phoenix metro area—a land of super-cooled malls where maintenance teams dust plants leaf by leaf in lounge areas outside Bulgari and Bottega Veneta—there’s a general sense that money will protect you from elemental dangers. It’s American individualism in its still-gilded glory, the belief you can buy and bunker your way to safety (though the dream has some gaps, like new subdivisions with no access to water).

But in southern parts of the city, literally across tracks of the city’s old train line, there was never any proof you could survive solo in the desert, certainly not on your salary alone. This is a part of town that was abandoned by local government in the city’s early days, so lacking in basics like sewers or sidewalks that it was once known as “the shame of Phoenix.” In a 2005 historical survey titled The Geography of Despair: Environmental Racism and the Making of South Phoenix…, three ASU scholars tracked the enduring legacy of what they labeled “Sunbelt apartheid” into modern times. The South Phoenix zip code where Wesley UMC sits is now 80 percent Latino and Black. Its residents have known for a century that they couldn’t gut out the rent, labor in the heat, or raise children without support from family, friends, neighbors, a cousin’s friend, a receptionist someone knew in an emergency room—a cultivated mutual aid network. Community has always been the difference between life and death there, and even if you have a strong one, high summer is dicey.

I’ve met hundreds of people in Phoenix, both North and South (which residents have re-named “South Mountain” to shed some of the old stigma), over the last two years, and despite the fact that local heat mortality rates are high and rising, I’ve yet to hear anyone say, “This place is a mistake.” They want to make it safe, to believe what David Hondula, who directs the city’s Office of Heat Response and Mitigation, told me in his 14th-floor downtown office in May: “We’re expecting things to get hotter. We don’t have to expect them to get worse.”

Hondula is now two years into his job, one of the handful of “Chief Heat Officer” positions that American cities like Miami and Los Angeles have added since 2021, as they realized crisis-weather was no longer an anomaly. On paper, a realm he’s quite comfortable in, Hondula is a perfect fit, a still-young, energetic researcher who’s published study after study on how various adaptation strategies could affect “heat-related mortality and morbidity in the future” (morbidity is what makes you sick; mortality is the succumbing). He joined the ASU staff in 2013, and much of his research has included Phoenix neighborhoods.

Hondula is the kind of thinker who will argue against himself in a second, always willing to chuck a conclusion if new data appears. His papers are filled with there’s-still-so-much-we-don’t-know caveats, noting a “large knowledge gap” about “climate-health intervention strategies.” Do excessive-heat warning systems really save lives? How about cool-pavement street coatings? More trees? Laws that keep utility companies from shutting off service in summer? Free air conditioners? More cooling centers?

Over the years, he’d come up with some theories of his own, but in the summer of 2022, he began finding out for real, in the most tangible ways. He joined volunteer outreach teams, pulling a red wagon through high-risk parts of Phoenix on the hottest days and offering people cold water, hats, and flyers with emergency phone numbers. What he found on the streets was both miserable and complicated—hundreds of people stranded in perilous conditions. A woman using a wheelchair who couldn’t find an accessible ride to a cooling center. Oven-hot tents pitched on blazing blacktop. Addicts heat-sick from the extra dehydration effects of meth and fentanyl. Folks lying listless and disoriented in slivers of shade. Once, he found a group sweltering just across the street from a cooling center they didn’t know about, despite a sophisticated online map of the region’s cooling sites.

All this made his years of academic research suddenly feel radically incomplete. “I can’t remember once writing about affordable housing. I’m sure the word ‘naloxone’ never appears in any paper I’ve written, or ‘overdose’ for that matter,” Hondula told me. “And I certainly did not understand as concretely what we were saying when we wrote terms like ‘barriers to accessing cooling resources.’”

Wesley volunteers started using the church's one washer and dryer to offer laundry services for the unsheltered.

In the middle of that first summer, some Harvard researchers came out with a study suggesting cooling centers weren’t really worth their hype and public investment. Hondula, fresh off streets where unsheltered people were, by his estimate, up to 300 times more likely to die from heat-related causes, responded that perhaps desk-bound data-heads (and he included himself) don’t know what they don’t know.

“I don’t want to say the paper is wrong,” he told local reporters. “But we have a different perspective.” He argued the city needed more places of respite. He knew the number of people without homes in Phoenix had more than doubled since the pandemic and was still rising. And Hondula could now predict, with demoralizing accuracy, that more people would die during his first year on the job than had the year before.

Another thing about the mortality data was emerging for him: Heat victims were often isolated, cut off from a protective web of family and neighbors. Week after week, the majority of people dying were unsheltered middle-aged white men.

“In the Maricopa County heat death data, people identified as Hispanic decedents have a lower heat-associated death rate than whites and other groups,” he said. “While there’s not formal evidence for why that’s the case, the strong family and neighborly ties? That’s the working theory.”

He wondered how to replicate that protective effect. “I think the social fabric between institutions and communities is possibly the most important investment for climate adaptation,” he said. “But I’d couch that with housing.”

I once asked Sylvia Harris, Wesley’s 41-year-old, justice-oriented pastor, “How do people describe you?” She had the cooling center howling when she answered in a flash, loud: “You mean when they’re not calling me a Bitch?”

Clarity is a Harris strength, and she was categorically pissed earlier this year as I was reading her parts of Hondula’s Summer 2023 Heat Response Plan, a document that described itself as “another milestone in the City of Phoenix's efforts to innovatively respond to the sustainability and resilience challenges posed by the city's climatic setting in the Sonoran Desert.” Harris had never met Hondula, but as a frontline observer of what Wesley’s visitors really needed, from housing to health care, she was no longer impressed with words from city officials about heat relief efforts.

"We can't do church the way we've always done," says Pastor Sylvia Harris, who led Wesley as it created a more full-service Resiliency Center for the community.

“It’s talking about an interactive map of cooling centers,” I began.

“It’s a crap use of resourcing to continue to fund that,” she said. “You’d be better off with social workers going out to where centers are located to directly sign up people for services.”

She wasn’t feeling the efficacy of the “Reusable Water Bottle Pilot Program” or “Heat Safety Messaging,” either. The report’s mention of an application to get FEMA money for backup power in cooling centers left her temporarily speechless. She sighed with the gravitas of a woman who’d spent the last year writing funding request letters. She’d just paid out $6,875, raised mostly from other churches, to upgrade the center’s electrical system and add a couple fans, but there wasn’t enough to replace its leaky rooftop heat pump. I closed the report and we paused a moment.

“Is government any help at Wesley?” I asked.

“No!” she shot back, unhesitating. “It’s not! It’s not there.”

Her frustration was shared by Mrs. Hill-Hicks and the few paid cooling center staffers, some of whom were couchsurfing with relatives and would become officially unsheltered during their time working at Wesley. It was a common problem—average rents in the neighborhood nearly doubled from 2015 to 2021. Meanwhile, Phoenix had become bad-famous for its lack of affordable housing, resulting in one of the nation’s largest and most dangerous tent cities (built, ironically, around a shelter) called The Zone. Superior Court Judge Scott Blaney ordered the city to clear the encampment starting in May 2023, but hundreds remained. Most of the Wesley regulars were scared to live in The Zone, so they slept around parks and behind a local Rite Aid.

Early on, Wesley could only afford to keep its cooling center open from noon to 6 p.m., Monday to Friday—it was barely enough for the regulars who still had to endure a blacktopped neighborhood where temperatures often didn’t drop below 90 at night. Pastor Harris and the team knew they had to shore up their community some other way.

So they adapted. When the heat season finally ended in 2022, they renamed themselves the Wesley Resiliency Center, and by summer 2023, they’d nurtured nongovernment relationships with more volunteers and a variety of nonprofits, the Arizona Faith Network most of all, to go after the deeper needs of the neighborhood. AFN is a regional network of religious groups, not just Christians, who help each other respond on-the-ground to all kinds of crises, but especially extreme heat. With financial support from AFN, Harris hired a spirited neighbor to run the operation this year: 37-year-old Zipporah Amie, a former pastor’s kid and mother of three who once navigated the Phoenix shelter system herself and made it through. She began coordinating and offering practical things that could keep Wesley’s visitors fortified—a phone, diabetes meds, utility assistance, help with the endless forms it takes to get a rent voucher, rides from detox to rehab, and (always) food.

“Trust and believe, we’re going to be ready and suggesting services,” Amie told me as the temps shot up astronomically this summer. “Yes, here’s some food and water, but how about therapy? How about detox?”

Phoenix homeless advocate Austin Davis is a go-to resource for center visitors, helping them navigate the shelter system and find rides to detox.

Focused on this long game, the Wesley team developed their own list of hotline numbers, and the one they’ve used the most is the personal cell of a young poet turned homeless advocate named Austin Davis.

“One thing I say is that loneliness is the silent killer on the streets,” Davis told me on a brutal summer day he spent helping a man with a wound festering so badly there were maggots. “Community is the key to everything. The individual thing? Like, fuck that. You need a team.”

The Wesley Resiliency Center has been pushed to its limit over the last two blistering months. While the staff persisted in getting regulars hooked up to any available help (and they were agnostic about sourcing—sometimes it was just volunteers offering a $20 bill on the spot), the extreme heat anomaly had Wesley’s two rooms operating beyond capacity. They ran out of space for people to sleep and had to offer naps in shifts. They watched unsheltered people fashion dog shoes out of cloth and tape to prevent the 180-degree pavement from burning paws.

In the midst of all this, Pastor Harris was “called” (as they say in the Methodist church, which typically moves pastors every three to five years) to lead another church in Arizona. But she was pleased that her replacement, Rev. Towanda NT Connelly, came with a quarter-century of experience in social work, and the Resiliency Center stayed open. Mrs. Hill-Hicks and Mrs. McCray sometimes couldn’t make it longer than three hours on the hottest afternoons, but they kept coming.

“People are so tired of the struggle,” Mrs. Hill-Hicks told me in early August, right after the daytime highs had come down to 108. “We had a man in here cussing everyone out and throwing chairs, out of his mind. People snap at you. They don’t mean to, it’s just hot.”

She said she met a man from Scottsdale up north who told her he’d had $400K in the bank and a nice house, but a medical condition bankrupted him. He ended up on the streets, now part of the struggle.

“They think that money can protect them but it doesn’t,” she said. “And there by the grace of God go any of us.”

The type of mutual aid they’re offering at Wesley isn’t always enough to break cycles of poverty or addiction—Andrew’s been back, still subsisting on two cans of tuna a day and still considering detox—but, as center director Amie says, “We keep people alive until they are ready for that kind of change.” This as Maricopa County reports 558 deaths so far this year that were potentially heat-related (last year at this time, that number was 413).

"Our regulars aren't on that death toll list," says Zipporah Amie, who directed the Wesley Resiliency Center this summer.

“Our regulars aren’t on that death toll list,” Amie told me last week. “There’s many factors as to why, but I think it’s mostly because they found us. They soak up the fact that they can last. And they do.”

Pay attention to this small resiliency center in South Phoenix. Pay attention to any group of neighbors organizing help for each other when the stakes are life and death. There will, unfortunately, be plenty of examples, Maui the heartbreaking latest. Vulnerability is ubiquitous now. “Official” networks go down. The ancient wisdom of circling up with the people right around you and preparing for the worst together? That’s a habit South Phoenix never lost. Though it came through the crucible of low-income living, it’s a working survival strategy today, and prescient. As Amie wrote on Instagram after assembling bags of food for neighbors on a 119-degree day in July, "If you thought we weren’t ready I hate to tell ya we are."