<href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/35969891@N08/3863606183/">DiggzDE</a>/Flickr

If cats have any rival as objects of internet fixation, it may be bacon. Over the years, the salty, fatty, sweet, crispy stuff has gained iconic status among hardcore foodies and fast food fans alike. Thus we get sites like Bacon Today, which delivers “Daily News on the World of Sweet, Sweet Bacon.” Or as a July Wired headline summed up the internet’s cured-pork fetish: “Zombies and Bacon: Manufacturing Memes.”

And so, when a British pork industry trade group issued a press release last week titled “Europe’s pork and bacon supply is contracting fast,” bloggers sniffed an easy post in a “bacon shortage” meme. And so the “baconpocalypse” was born, complete with cutesy blog posts about how we’ll have to cut back on bacon donuts and candy bars. Or as one business site insisted, “Forget adding on bacon to your cheeseburgers or the ‘B’ in that BLT.”

Of course, all of this is click-groping internet piffle, as Slate‘s Matt Yglesias showed. The UK pork industry’s press release wasn’t really about bacon specifically, but rather about pork in general. And while it’s true that a catastrophic drought in US corn and soy country means higher hog-feed prices and thus higher pork prices next year, the effect on American consumers will be minimal. Mother Jones’ own Asawin Suebsaeng showed that the alleged great bacon shortage will shave just a pound per capita off of US bacon production in 2013—leaving us with an ample 45 pounds of bacon per person to make do with over the year. Overall, US pork prices will rise just 2.5 to 3 percent next year, the USDA projects. Wendy’s will likely continue peddling its “Baconator” burger unimpeded.

While editors and bloggers gorged on a trumped-up baconpocalypse, they largely ignored a story with real implications for global food security: a new report on how how climate change will sharply reduce the productivity of the oceans, particularly in the global south, where hundreds of millions of people rely on the sea as a primary source of protein. The report, by American NGO Oceana, ranks the nations that are most vulnerable to a reduction in available fish brought on by climate change—that is, nations that will struggle to replace dwindling fish stocks with other foods. To create its rankings, Oceana looked for countries with low per capita incomes, high population growth rates, and high rates of malnutrition, and then looked at how climate change would effect their access to wild-caught fish.

Oceana points out that that climate change affects the oceans in two ways:

1) Steadily rising ocean temperatures. Since “marine species and their prey are adapted to a certain temperature range,” higher temperatures will send many of them fleeing tropical waters to “deeper and colder waters towards the poles.” But the loss of an important food source in the tropics won’t necessarily translate into a fishing boom in polar waters, because “these climate-induced invasions of new habitats could have serious ecological consequences, including the extinction of native species toward the poles.”

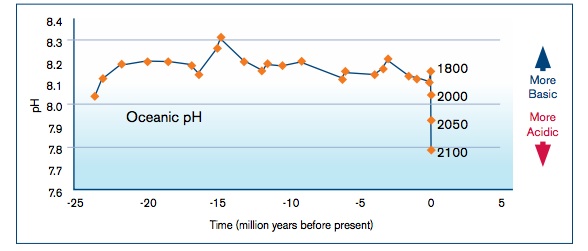

2) Acidification. As human activities spew carbon dioxide, the oceans take much of it up—and it causes Ph levels to drop. That means hard times for any species that develops a shell—think oysters, clams, and mussels—and any species that relies on coral reefs. According to Oceana, ocean Ph has plunged 30 percent since the Industrial Revolution—by far the most rapid drop in known history. And levels are expected to continue drop as CO2 emissions increase over the rest of the century. Here is a sobering chart:

“The rapid change in ccean pH since the Industrial Revolution is likely the fastest in Earth’s history.” Oceana

“The rapid change in ccean pH since the Industrial Revolution is likely the fastest in Earth’s history.” Oceana

As a high-income nation, the United States didn’t make Oceana’s rankings. But the report did offer a stark comment on how climate change will affect US fisheries: By midcentury, the continental United States could lose an average of 12 percent of its fisheries’ catch potential, representing a loss of more than 600,000 tons of edible fish annually. Alaska’s abundant fishery could benefit as fish flee northward in search of colder waters, but it faces perils, too, both from the potential for harmful invasive species and from acidification. Here’s Oceana:

Alaska may also be one of the hardest hit regions by the impacts of ocean acidification, which will be worsened toward the poles because cold waters absorb more carbon dioxide. Ocean acidification threatens pteropods, tiny marine snails and other small animals at the base of the food web, and losses in their populations could ripple up to impact populations of commercially important fisheries for salmon, mackerel, herring and cod.

But in terms of food security, the most threatened nations are low-income ones in the global south, Oceana stresses. Many island and coastal nations—which for obvious reasons have historically relied heavily on seafood for sustenance—are essentially screwed, as are the hundreds of thousands of small-scale fisherperople who rely on the sea for a living.

And it’s not just small countries like the Comoros or Togo that are at risk. Oceana ranks Indonesia as the 23rd-most vulnerable country to food security threats from climate change and ocean acidification. More chillingly, the United States’ frenemy Pakistan ranks eighth. The top 10 list of nations whose access to fish is vulnerable to climate change specifically (but not to acidification) includes such geopolitical flashpoints as Iran, Libya, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.

Many of those countries, of course, already have limited food-production capability because of desertification. The more oil-rich of those countries, of course, will likely be able to buy food from elsewhere to make up for falling fish stocks—but that just means more pressure on regions like Africa, which are already experiencing petroleum-funded “land grabs.”

There is a bacon angle to all of this, too. China ranks 35th on Oceana’s list of most vulnerable nations. As it adjusts to relying less on the sea for protein, its already fast-growing demand for pork will likely accelerate. As I reported in June, the nation is already importing massive, increasing amounts of US-grown pork. As long as China reigns as electronics maker to the world, it will have plenty of cash to continue doing so. As the oceans’ productivity withers under climate change, the United States may emerge as the CAFO (confined animal feedlot operation) to the world—and Chinese consumers may have the buying power to outbid you for bacon. That factor really could swipe the “B” out of your BLT and the bacon off of your bacon cheeseburger.

But who wants to ponder a future of cutthroat global competition for resources, when we could be fixating on silly internet memes?