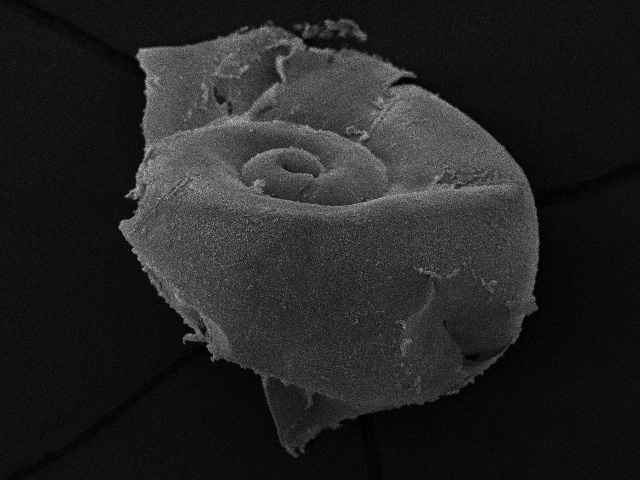

The marine snail Limacina helicina antarctica showing acute levels of shell dissolution in Southern Ocean where deep-water upwelling and ocean acidification combined to reduce aragonite saturation in surface waters. This specimen was alive at capture: Image provided by Nina Bednarsek and Bernard Lézé

The marine snail Limacina helicina antarctica showing acute levels of shell dissolution in Southern Ocean where deep-water upwelling and ocean acidification combined to reduce aragonite saturation in surface waters. This specimen was alive at capture: Image provided by Nina Bednarsek and Bernard Lézé

A new paper in Nature Geoscience reports the first evidence of marine animals dissolving in acidified waters off Antarctica. The pteropods—also called marine snails or sea butterflies—were found in waters 656 feet (200 meters) deep, alive but suffering severe shell damage from a combination of natural upwelling and human-caused ocean acidification.

Natural upwelling is triggered by strong winds that drive deep cold water from the bottom to the surface. We know that many upwelled waters are corrosive to animals like sea butterflies which use aragonite to build shells. But the saturation horizon for aragonite in the Southern Ocean typically occurs at around 3,280 feet (1000 meters) deep—far below where Limacina helicina antarctica live. So what happened to hoist that horizon line 2,625 feet (800 meters) closer to the surface?

Live Limacina helicina antarctica with intact shell and its wing-like “butterfly” parapodium trailing behind: Russ Hopcroft, University of Alaska, Fairbanks via NOAA Ocean Explorer

Live Limacina helicina antarctica with intact shell and its wing-like “butterfly” parapodium trailing behind: Russ Hopcroft, University of Alaska, Fairbanks via NOAA Ocean Explorer

The answer is ocean acidification (OA)—the result of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning leaching from the atmosphere into the ocean and changing its pH. (I wrote more about that here and here and here, and about how ocean chemistry is measured in my “Arctic Ocean Diaries” here.)

Numerous lab experiments have demonstrated that OA has the potential to damage marine organisms who make shells or skeletons. This paper reports the first evidence that OA is already damaging marine life in the Southern Ocean.

And not just any marine life. Marine snails are a vital part of the food web of Antarctic waters, supporting zooplankton, fish, birds, marine mammals, and us. (Read Tom Philpott’s piece on the correlation between OA and human food here.)

Marine snails are also important players in the Southern Ocean’s carbon cycle—the shuttling of carbon between atmosphere and ocean. In that work they’ve mitigated a lot of our C02 emissions. Too many for their own good, apparently.

Co-author and science cruise leader, Geraint Tarling from the British Antarctic Survey, says:

Although the upwelling sites are natural phenomena that occur throughout the Southern Ocean, instances where they bring the ‘saturation horizon’ above 200m will become more frequent as ocean acidification intensifies in the coming years. The tiny snails do not necessarily die as a result of their shells dissolving, however it may increase their vulnerability to predation and infection consequently having an impact to other parts of the food web.

The paper:

- N. Bednaršek, G. A. Tarling, D. C. E. Bakker, S. Fielding, E. M. Jones, H. J. Venables, P. Ward, A. Kuzirian, B. Lézé, R. A. Feely & E. J. Murphy. Extensive dissolution of live pteropods in the Southern Ocean. Nature Geoscience (2012). DOI:10.1038/ngeo1635