<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/baboon/305620006/sizes/l/in/photostream/">baboon</a>/Flickr

Should sugary drinks be taxed to discourage people from overconsuming them? That’s the question California voters in Richmond and El Monte are asking as they head to the polls today to decide on what could become the first penny-per-ounce taxes imposed on sugary beverages by cities in the US.

As I reported in June, some economists and public health researchers think that soda has enough price elasticity that its consumption rates would be shaken up by such measures. And growing research about diabetes and other health problems associated with the overconsumption of sugar—as discussed in the recent Mother Jones exposé “Big Sugar’s Sweet Little Lies,” for instance—has convinced some it may be time for the government to help regulate its consumption.

Just in time for today’s election, a new study presented at a conference last week underscored the potentially positive role such excise taxes could play in problems plaguing minorities and low income communities. When researchers from the University of California—San Francisco and other universities projected the impact of a 20 percent drop in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in California, they found that incidence of diabetes and heart disease would drop up to 5.6 percent and 1.2 percent, respectively.

But more importantly, the researchers found, incidence would decrease more significantly for certain groups who struggle with these issues the most: Mexican Americans, African Americans, and poor people. For these groups, a soda tax could decrease diabetes incidence by around 8 percent, and heart disease by around 2 percent. Total savings associated with avoiding these health issues in California? As much as $1 billion for diabetes, and an extra $130 million for heart disease.

Richmond’s councilman Jeff Ritterman, who proposed the city’s soda tax, or “Measure N,” called these research findings “the smoking gun” in an email in early November, especially considering two-thirds of the city is black or Latino, and 32 percent of school kids are obese. The city also suffers from an 11 percent unemployment rate and high rates of poverty. As California Watch reported, the lead researcher of the study thinks the findings are significant because they show that some groups that in general drink more soda and are at a higher risk of diabetes may also benefit most from a tax on SSBs.

The taxes are by no means universally popular. Many in the Richmond area, including some black and Latino leaders, feel they were left out of the soda tax discussion and worry that a tax could slow sales at local small businesses. As the debate heated up over the summer and fall, these opponents were encouraged by the likes of, who else? Big Soda.

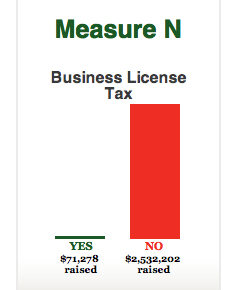

Maplight.orgAs my colleague Kate Sheppard reported, the American Beverage Association bankrolled a coalition against the tax in Richmond, framing it as a “tax on poor people.” (This coalition also successfully sued the city to not have to disclose its donors on campaign fliers). Data compiled at the end of October by Maplight.org shows that groups like the ABA, Coca-Cola, and PepsiCo have outspent supporters of Measure N at a ratio of 35 to 1. The soda industry reportedly spent another $1.3 million to defeat El Monte’s soda tax. Whatever the outcome of today’s election, the outsize spending reveals just how far the beverage industry will go to protect its product, even if the public health consequences are less than sweet.

Maplight.orgAs my colleague Kate Sheppard reported, the American Beverage Association bankrolled a coalition against the tax in Richmond, framing it as a “tax on poor people.” (This coalition also successfully sued the city to not have to disclose its donors on campaign fliers). Data compiled at the end of October by Maplight.org shows that groups like the ABA, Coca-Cola, and PepsiCo have outspent supporters of Measure N at a ratio of 35 to 1. The soda industry reportedly spent another $1.3 million to defeat El Monte’s soda tax. Whatever the outcome of today’s election, the outsize spending reveals just how far the beverage industry will go to protect its product, even if the public health consequences are less than sweet.