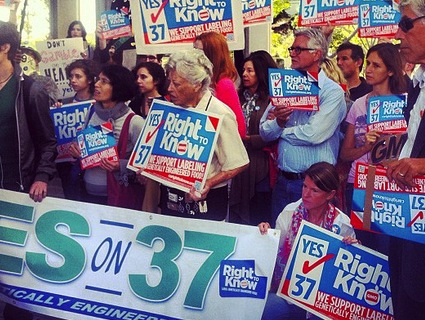

A rally in favor of Proposition 37 at Los Angeles City Hall in October. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/ammichaels/8122518497/">CheeseSlave</a>/Flickr

In his recent “Guide to California’s Ballot Mayhem,” my colleague the prominent political blogger Kevin Drum came out against Prop. 37, which would require that all foods containing genetically modified (GM) ingredients be labeled.

In general, Drum says, he opposes the propositions that appear on his home state’s ballots unless he sees a clear case for them. For him, Prop. 37 fails that test. “‘l confess to mixed feelings about this,” he writes. “But I’m afraid mixed feelings mean a No vote.” Kevin is agnostic on the merits of compulsory labeling of GM foods. “I respect the desire to know where your food comes from, regardless of whether you want to know different things than I do, but on a substantive level I’m not convinced that GM foods pose enough of a genuine hazard to rate detailed labeling laws that are etched in stone forever.”

It’s technical issues push that Kevin to the “no” side. He writes: “as with so many initiatives, [it’s] sloppily written; it can’t be changed after it’s passed; and it imposes expensive state labeling burdens on interstate commerce, something that I’m increasingly leery of.”

I’ve written a lot about the hazards, potential and realized, that GM crops bring to bear: the complete domination of them by a handful of large companies, the accelerating pesticide treadmill on which they’ve placed farmers, and the still-little-tested potential health risks. For all of these reasons, I avoid GMOs, and would vote to require their labeling if I had a chance.

For now, I’d like to set those aside and respond to Kevin’s technical concerns. I agree that California’s ballot initiatives tend to be blunt instruments called upon to do delicate work. It seems to me that the state’s meta-problem—the reason its public schools are a mess, the reason it keeps hacking away at its glorious public-university system—can be tied to the infamous, 1978 Prop. 13, still limiting property taxes and squeezing civic institutions a quarter century after its passage.

But I think the effort to label GMOs calls for the use of one of those admittedly unwieldy ballot initiatives. That’s because at the national level, the GM seed/agrichemical giants, with their well-heeled lobbying efforts, have managed to stymie all other democratic means for reining them in.

In a 2003 paper (PDF) for New York University’s Center on Environmental and Land Use Law, Emily Marden describes the fragmented, sieve-like process through which genetically altered traits move from lab to supermarket in the United States. Before the first commercial GM crops ever hit farm fields in 1996, Marden reports, the federal government essentially committed itself to not regulating the novel technology. Since the early 1990s, Marden shows, two key assumptions have shaped the official US response to GMOs:

- That the technology poses minimal—at most—public-health and ecological risks; and

- That GMOs needn’t be regulated differently than any other foods. As a result, gene-altered organisms have been allowed to suffuse our food supply without any real effort to measure their risk. These decisions were made at the urging of industry, despite serious pushback among scientists within the Food and Drug administration, as this 2000 Mother Jones piece shows. (Here are internal FDA documents from the ’90s, in which agency scientists raise objections.) Since the federal regulatory agencies decided to view GMOs as “substantially equivalent” to conventional foods, labeling—required in Europe—has never seriously been considered here.

This laissez-faire regime has congealed under President Obama. While campaigning in 2007, Obama vowed he would push labeling of GM foods, “because Americans have a right to know what they’re buying.” And that’s the last we’ve heard of that principle—Obama’s FDA has shown no sign of budging on national labeling.

But there are other ways besides the administration could have stood up to the GMO industry. Early in President Obama’s term, the US Department of Agriculture hinted it would restrict planting of Monsanto’s new herbicide-tolerant alfalfa product to protect organic farmers’ crops from genetic cross-pollination with GM crops. In the agency’s environmental impact statement for GMO alfalfa (PDF), it acknowledged that: 1) “gene flow” between GM and non-GM alfalfa is “probable,” and could threaten organic dairy producers and other users of non-GMO alfalfa (although at another point in the large document, the agency calls the risk of cross-pollination “minimal”); and 2) widespread use of GM alfalfa threatened to create yet more weeds resistant to Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide, which would require ever-higher doses of Roundup and application of ever-more toxic herbicides. The report noted that 2 million acres of US farmland already harbor Roundup-resistant weeds caused by other Roundup Ready crops.

But then the administration abruptly switched course and deregulated biotech alfalfa without restriction. And its reasoning might actually have been correct—as I explained in two posts last year (here and here), the USDA’s ability to regulate GMO crops was structured in the 1990s to be so weak that it has little standing to restrict crops even when it foresees potential harm, as in the case of alfalfa. Essentially, the agency has given up trying. Meanwhile, in Congress, the industry has been extremely successful in using its lobbying might to insert riders into legislation that would strip away the final vestiges of public oversight.

That’s where California voters come into play. If the federal government can’t regulate GMOs, much less require labeling, it makes sense for citizens to push back at the state level. The Center for Food Safety, an NGO that promotes the precautionary principle in regulating novel technologies, has been at the forefront of the effort to push labeling at the state level. Andrew Kimbrell, executive director of the CFS, told me via email that the labeling movement has been vexed because state-legislature agriculture committees tend to be “heavily influenced by agribusiness” making it “extremely difficult to get a genetic engineering labeling bill considered much less passed.”

CFS and its allies have tried to get a labeling bill introduced in the California legislature “many times,” Kimbrell told me. But these efforts, in California and elsewhere, have failed “because of industry influence and pressure.” Hence Prop 37, which made the ballot this summer when it got a million signatures from Californians. The idea was to bypass industry-backed politicians and take the case directly to voters.

Kevin may in the end get his way—Prop. 37’s fate in next week’s ballot suddenly looks pretty grim. As recently as Sept. 27, the initiative held a 3-to-1 lead in a poll by Pepperdine University. But after a blitz of cash from the agrochemical and Big Food industries and a relentless TV-commercial campaign, Prop. 37 the Pepperdine poll had losing 50 to 39 as of Oct. 30. If that result holds, the industry will have yet again used its vast financial resources, won with oligopoly power over its markets, to stave off serious public oversight.