Burger: <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-115608694/stock-photo-big-hamburger-on-white-background.html?src=82b4146a35336d2b015760d2ee157948-1-28"> rvlsoft </a>/Shutterstock; water glass: <a href="hhttp://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=glass+of+water&search_group=#id=60578782&src=5c1a42e0e183a0d944ecc68827d68763-1-0"> ILYA AKINSHIN</a>/Shutterstock

In a recent piece, I fretted about one problem with our reliance on industrially produced fertilizers: They come from scarce and nonrenewable sources, meaning we’ll eventually run out of them. But there’s another, much more immediate downside to the synthetic nitrogen and mined phosphorus that drives industrial agriculture: They tend to leach out of soil and foul up water, both for drinking and recreation.

Environmental Working Group has just released an excellent report (available here) on the impact of that pollution on water quality in Iowa, ground zero of US industrial agriculture. The condition of that state’s water is, in short, dismal. EWG looked at data kept by Iowa’s Department of Natural Resources on 72 free-flowing streams across the state, comparing the 1999-2002 period and the 2008-11 period. In the chart, right, note that the majority of streams are rated either “poor” or “very poor”—and that the situation has improved little if at all over time. The main culprits are nitrogen and phosphorus. Here’s EWG:

The two pollutants most responsible for poor water quality ratings in the Index are nitrogen and phosphorus. In 55 percent of the monthly samples across all sites, nitrogen was the single worst pollutant, followed by phosphorus in 30 percent. Together, high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus set off a cascade of pollution problems that contaminate drinking water and damage the health of Iowa’s streams and rivers.

The health consequences are dire. Even at low levels, nitrates can cause reproductive and thyroid problems, while phosphorus, along with nitrogen, feeds toxic blue green algae blooms in lakes.

Now, Big Ag would like you to believe that much of the nutrient load in streams comes from municipal sewage and industrial runoff. That’s absurd. Citing Iowa DNR numbers, EWG debunks that claim, reporting that just 8 percent of the nitrogen and 20 percent of the phosphorus polluting Iowa’s streams comes from those sources. The rest comes from “non-point sources”—mostly agriculture. And whereas runoff from sewage and industrial operations is heavily regulated by the state of Iowa, EWG points out, water pollution from crop production isn’t.

It’s worth delving a bit into just how central Iowa is to the US food system. Iowa’s farmers are the leading producers of the most prodigious US crops, corn and soy. Corn literally dominates the state. Of the state’s total land mass—including cities—of 35.7 million acres, 14 million acres was planted in corn in 2011. Much of the rest—another 9.4 million acres—went to soybeans. Altogether, then, industrial agriculture’s two favorite crops covered two-thirds of the state’s land mass.

All of that corn and soy means a veritable cascade of fertilizer. Corn is by far the most fertilizer-intensive US crop—it takes up about 29 percent of US farmland, but sucks up 45 percent of nitrogen and 47 percent of phosphorus used on farms each year. Soybeans need very little nitrogen—like all legumes they fix nitrogen into the soil from air. But they do require phosphorus: About 16 percent of all US phosphorus goes to soy. (Source: USDA Excel file.)

Of course, Iowa is famous for one other crop: hogs. As with corn and soy, Iowa leads the nation in swine production, raising nearly a quarter of the nation’s pork, the great majority of it in large confined operations known as CAFOs. These facilities essentially take in corn and soy and convert it into meat and manure—manure that’s rich in nitrogen and phosphorus. CAFO operators apply as much as possible of the stuff to surrounding land, but there’s way more manure than can be used without running up huge hauling feeds. So they have an incentive to apply more than their land can handle—meaning runoff and pollution. CAFOs, and the mountains of manure they generate, are regulated by the state, EWG points out, but the system is, well, porous. “State officials are currently responsible for enforcing water pollution regulations on CAFOs,” EWG reports, “but the federal EPA has criticized state officials for lax regulation and warned that it might take over.”

As a result of unchecked runoff from farm fields and inadequately monitored hog production, Iowa’s waterways have become a kind of sacrifice zone for the US food system. The problem is worst of all in the summer, when Iowans are most inclined to enjoy those waterways and 80 percent of the state’s monitored streams typically have “poor” or “very poor” water quality (see chart, left).

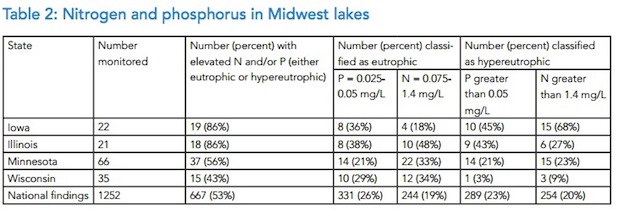

In another, broader report released back in April, EWG teased out the broader implications for drinking water in the corn-intensive state of the Midwest: Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. USDA economists estimate that removing nitrate alone from drinking water costs more than $4.8 billion a year, EWG reports. And despite the expense, the effort too often fails: “In Iowa, for example, 17 percent of residents—about 500,000 people—were exposed to high nitrate levels in drinking water between 1998 and 2005, the second highest rate in the nation”

Even at levels below the EPA’s legal limit, nitrates can cause reproductive problems, EWG reports, adding that recent research links low-level nitrate intake to thyroid cancer.

As for phosphorus, it’s not directly poisonous to humans at low levels, but it, like nitrogen, feeds the vast algae blooms that have become a major menace, not just in the Gulf of Mexico and the Chesapeake Bay, but also in the Midwest’s lakes. (For more on this story, see Jessica Marshall’s article for the Food & Environment Reporting Network released this fall.) Check out how bad lakes in Illinois (another corn/soy/hog powerhouse) and Iowa look in the chart below—note that eutrophic and hypereutrophic lakes are “at risk of algal blooms that would affect recreation and drinking water quality.”

As the algae blooms die, they produce nasty stuff called cyanotoxins, which, when consumed, “can harm the nervous system, cause stomach and intestinal illness and kidney disease, trigger allergic responses and damage the liver,” EWG reports.

Worse, when organic matter from algae blooms meets chlorine and other chemicals municipalities use to disinfect tap water, yet more nasties are generated.

The reaction between chlorine and algal organic matter generates trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids, two types of disinfection byproducts that are federally regulated, as well as many other types of toxic byproducts. A study sponsored by the U.S. EPA and

the Water Research Foundation found that algal blooms also lead to formation of highly carcinogenic nitrogenous disinfection byproducts, which are not currently regulated.

In short, in order to supply the food system with the mountains of corn and soy it transforms into cooking fat, meat, sweetener, and a range of common ingredients, we’re threatening the drinking water of millions of people in the Midwest, and forcing them to pay billions of dollars each year in a futile effort to clean it up. EWG’s two reports contain multiple recommendations for fixing the situation, all of them worthy. But to me, the situation boils down to this: We have to diversify our agriculture away from its fixation on two crops and related products like feedlot pork, beef, or chicken. We can’t blanket tens of millions of acres of farmland in a resource-intensive crop like corn and expect to enjoy clean water.