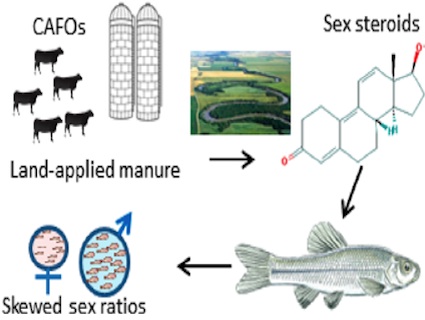

An infographic from a new paper suggesting that synthetic hormones from factory farms are affecting the sexual development of fish in nearby streams. From: <a href="http://www.environmentalhealthnews.org/ehs/news/2012/leet-estes302599t.pdf"><em>Enviromental Science and Technology</em></a>

In his 1977 classic The Unsettling of America, Wendell Berry described a major change that came along with the post-World War II rise of factory-scale animal farms.

“Once plants and animals were raised together on the same farm—which therefore neither produced unmanageable surpluses of manure, to be wasted and to pollute the water supply, nor depended on such quantities of commercial fertilizer,” Berry wrote. “The genius of America farm experts is very well demonstrated here: they can take a solution and divide it neatly into two problems.”

On diversified farms, manure is a vital resource that’s used to build fertility and organic matter in soil. But when you cram animals together by the thousands, you generate way more manure than can be absorbed by nearby land—and your vital resource suddenly becomes a waste problem. The tendency is to over-apply manure in fields surrounding factory farms—which then runs off into streams, helping fertilize the algae blooms that plague the Midwest’s lakes, which I reported on last week.

But it’s not just excess phosphorus and nitrogen that’s the problem. It’s also the hormones and other chemicals fed to confined animals—they, too, end up in their manure and thus into waterways. A quarter century after Berry’s observation, we’re just now figuring out the implications. A team of scientists from Purdue and the Environmental Protection Agency looked at fish populations in Indiana streams downstream from CAFOs, or confined-animal feedlot operations. Their findings, released this month, are sobering. In CAFO-tainted water, 60 percent of minnows turned out male. In the non-contaminated water, the male ratio was 48 percent. The CAFO-exposed water also showed lower species biodiversity, and the fish in them had reduced fertlity.

The takeaway is that CAFO manure running into streams appears to be affecting the sexual development of fish. Although it’s impossible to pinpoint an exact cause, the authors point out that the CAFO water showed heightened levels of synthetic hormones used in livestock farms “during the period of spawning, hatching, and development for resident ?shes.”

And one of those hormones, trenbolone, has also turned up as a possible culprit in other studies, reports Environmental Health News:

The same synthetic hormone, trenbolone, detected at high levels in the Indiana streams was linked to an all-male population of zebrafish in a 2006 laboratory study by University of Southern Denmark researchers. In addition, a study led by Orlando in 2004 found male minnows in a stream near a confined animal feeding operation had lower than average testosterone and were sexually immature.

Like all individual studies, the current one is suggestive, not definitive. But it raises serious questions about what we’re sacrificing to feed our appetite for cheap meat.