A large hog farm and its ammonia–spewing "manure lagoon." <a href="http://photogallery.nrcs.usda.gov/netpub/server.np?find&catalog=catalog&template=detail.np&field=itemid&op=matches&value=1975&site=PhotoGallery">USDA/NRCS</a>

Late last year, US Department of Agriculture chief Tom Vilsack boasted that US agriculture exports had hit an all-time high in fiscal 2013, and hailed “historic work by the Obama Administration to break down barriers to US products and achieve new agreements to expand exports.” Underlying Vilsack’s glee is the idea that growing huge amounts of food here and selling a big chunk of it overseas bolsters the US economy and stabilizes rural America.

That kind of thinking has driven agriculture policy at least since the days when Richard Nixon’s ag secretary Earl Butz exhorted farmers to scale up operations and plant “fencerow to fencerow” in order to supply foreign markets.

But a new paper (PDF) from Harvard suggests massive ag exports might not be the economic boon imagined by USDA secretaries. The researchers looked at a single farm pollutant, ammonia (NH3), which makes its way into the air from fertilizer applied to farm fields and from the manure that accumulates on livestock farms. Once it enters the atmosphere, as Erik Stokstad explained in an excellent (pay-walled) news item in Science, it “reacts with other air pollutants to create tiny particles that can lodge deep in the lungs, causing asthma attacks, bronchitis, and heart attacks.”

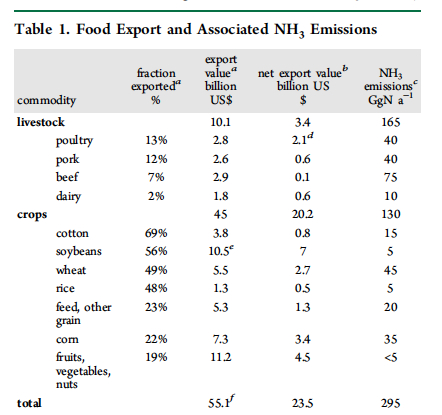

The Harvard team found data on the ammonia emissions associated with various major crops and meat products between 2000 and 2009, calculated what percentage of each commodity goes to exports, and figured out what share of total ag-based ammonia emissions come from growing food for export.

Having calculated the total, they set about figuring out the public-health costs associated with all of that export-driven ammonia billowing about in the air we breathe. The results, as our friends at UpWorthy might say, will astonish you—but not in a warm and fuzzy way. They calculated that our agricultural exports cause $36 billion in annual ammonia-realted healthcare costs, along with about 5,100 premature deaths.

Now, $36 billion might seem somewhat modest compared to the total value of US ag exports, which as Vilsack recently announced, have surged to a record. But the headline export numbers are raw—they don’t account for how much farmers spent to produce their export-bound bounty. When the researchers looked at the 2000-2009 period and averaged total exports minus production costs, they found that the net value of US ag exports came in at about $23.5 billion annually (see chart above).

Thousands of deaths aside, simple math—$23 billion in gains vs. $36 billion in costs—suggests that the US policy of pushing ag exports is a net economic loser. And as the authors make clear, ammonia emissions are only one of the hidden costs associated with large-scale agriculture. Others include eutrophication (fertilizer-fed dead zones in lakes and deltas), loss of biodiversity, and greenhouse-gas emissions, including another by-product of excess fertilizer and manure, nitrous oxide.

Of course, the $36 billion in costs associated with ammonia emissions don’t affect the bottom lines of the gigantic meat and grain-trading firms that move all that meat and grain from here to foreign markets. Nor does it affect the input suppliers that sell farmers the fertilizers and pesticides to grow the grain that’s exported, both directly and in the form of grain-fed beef, pork, and chicken. Such costs are what economists call “externalities”—burdens that fall not on the corporations that profit from making a problematic good, but rather on society as a whole.

And that’s a pretty good deal, if you’re in the business of, say, producing pork in the US for the booming Chinese market. No wonder a Chinese company bought US pork giant Smithfield last year.