DanielPrudek/iStock/Getty

Bees are in a world of trouble right now. A few years ago, the US Environmental Protection Agency took some steps to protect the insects by limiting the use of an insecticide called sulfoxaflor. Made by Corteva, the agricultural arm of DowDupont, sulfoxaflor is “highly toxic to bees and other pollinating insects,” and it also appears to harm wild pollinators like bumblebees at low doses. In 2016, under pressure from a lawsuit by environmental groups and a federal court order, the agency severely limited use of the insecticide.

On Friday, the EPA undid many of those restrictions, expanding the bug killer’s potential domain to corn, soybeans, cotton, alfalfa, millet, oats, pineapple, sorghum, tree plantations, citrus, squash, and strawberries. These crops cover a massive amount of land and represent a huge prospective market. In a typical year, corn, soybeans, alfalfa, and cotton are planted on about 190 million acres—a combined land mass equal to nearly two Californias. So the decision marks a vast expansion of territory on which bees could encounter sulfoxaflor.

Environmental groups were aghast. “The Trump EPA’s reckless approval of this bee-killing pesticide across 200 million US acres of crops like strawberries and watermelon without any public process is a terrible blow to imperiled pollinators,” Lori Ann Burd, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s environmental health program, stated in a press release. Greg Loarie, an attorney for Earthjustice, called the decision “nothing short of reckless.”

The decision to dramatically broaden the scope of sulfoxaflor use is the second time Trump’s EPA has defied scientific consensus in favor of an insecticide marketed by Dow, one of Corteva’s corporate predecessors. In March 2017, the agency reversed a decision made late in the Obama administration to ban chlorpyrifos, a widely used bug killer known to damage kid’s brains at low exposure levels. Dow, then still a standalone company, had contributed $1 million to the president’s inaugural committee.

The sulfoxaflor move also marked the second swipe the Trump administration took at bees in less than two weeks. On July 1, the US Department of Agriculture decided that the government simply can’t afford to track the health of honeybees, the insects we largely rely on to pollinate about one-third of the crops we eat. The department announced it was nixing its Honey Bee Colonies survey, which tracks annual hive losses sustained by beekeepers.

“The decision to suspend data collection was not made lightly but was necessary given available fiscal and program resources,” a USDA press release stated. It did not reveal how much money will be saved by axing the program, which started in 2015 as part of President Barack Obama’s Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators.

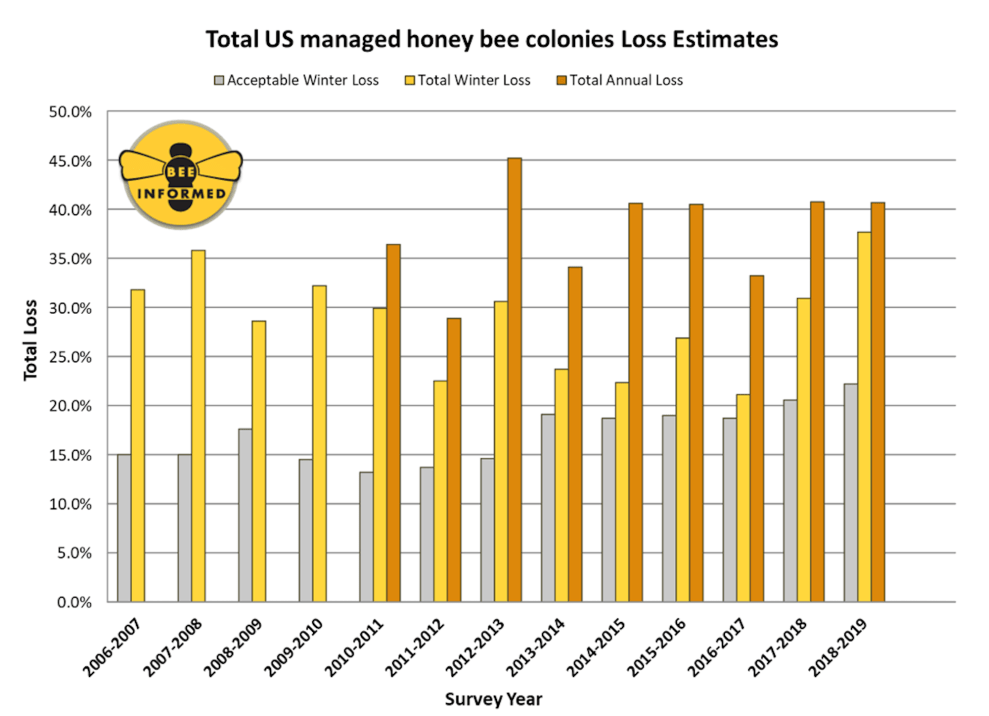

The Trump administration’s moves sting bees when they’re down. In June, an annual report by a group of university researchers called “The Bee Informed Partnership” found that the country’s beekeepers lost nearly more than 35 percent of their honeybee colonies over the 2018-2019 winter—the highest level recorded since they started tracking hive losses in 2006.

Including summer losses, beekeepers lost 40.7 percent of their hives over the year ending April 1, 2019, about average for recent years. Such regular annual losses, which began in the mid-2000s, put enormous stress on the beekeepers who haul their hived around the country to pollinate some of the nation’s biggest cash crops, including California’s almonds—which require a staggering 85 percent of the nation’s managed hives during the spring bloom.

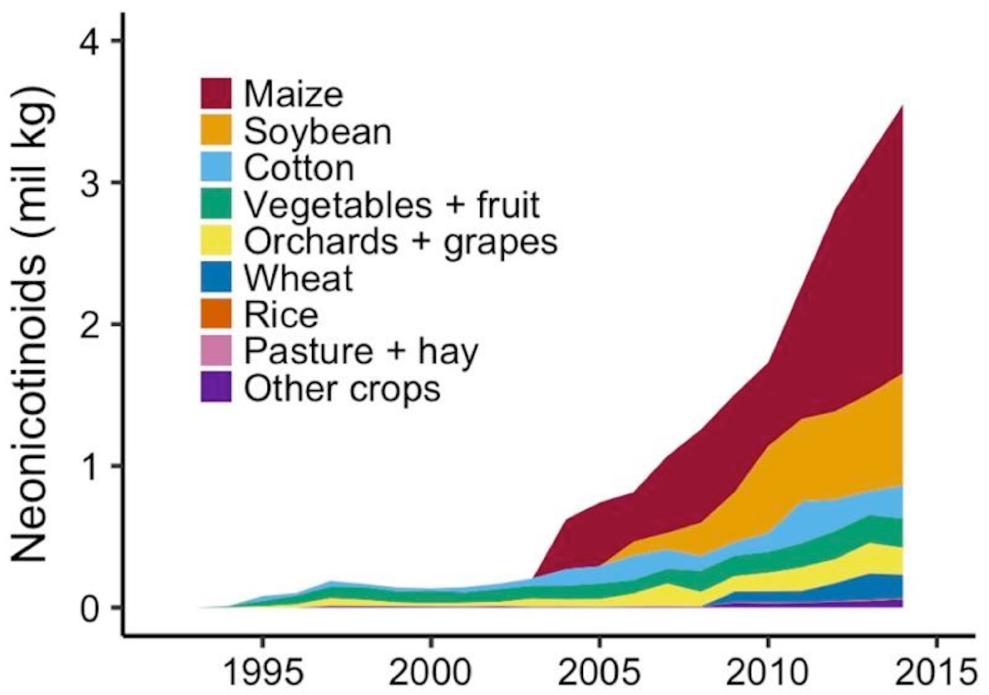

Meanwhile, new research suggests more trouble ahead for bees. They face a variety of stressors, including loss of good foraging ground, agricultural pesticides, and a pathogenic parasite called the varroa mite. A study released last month, led by researchers from the University of Bern in Switzerland, found that low-level exposure to a widely used class of insecticides called neonicotinoids made bees much more susceptible to varroa mites, and the combination “significantly reduced survival of long-lived winter honeybees.”

The study adds to a huge body of research implicating neonics in the dire health of pollinators. Their use on US farmland has exploded in recent years, on tens of millions of acres across the country, from California’s citrus groves to the Midwest’s corn and soybeans to Florida’s tomato fields.

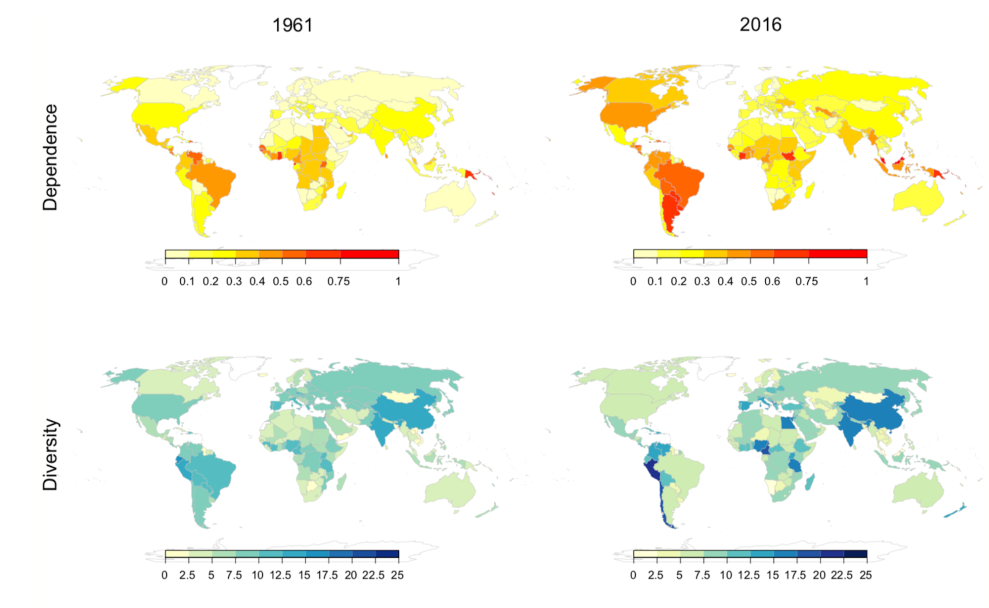

Meanwhile, another study an international team of researchers, including University of Maryland biologist David Inouye, found that even as stresses on pollinators ramp up and their health declines, farmers in the United States and globally are devoting more and more acreage to crops that require insect pollination. They found that between 1961 to 2016, global area pollinator-dependent crops jumped 137 percent.

One way to keep the bees we rely on for food production healthy is to plant a variety of crops, because, say, a vast grove of almond trees represents a “cornucopia of food” for a few weeks, it requires pollinators and beekeepers to move quickly to find other food sources when the bloom finishes. The researchers found that in the United States and many other countries, reliance on insect pollination has expanded dramatically even as crop diversity has waned.

In the below chart, taken from the paper, “dependence” is the proportion farmland devoted to pollinator-dependent crops; and “diversity” is measure of major crops grown in a region.

Our honeybees live under enormous stress, beset by parasites, pesticides, long-haul travel, and vast and expanding monocrops in need of their services. By adding yet more insecticide stress to their lives and trashing a program that tracks their health, Trump is kicking an already-struggling ecological hornet’s nest.