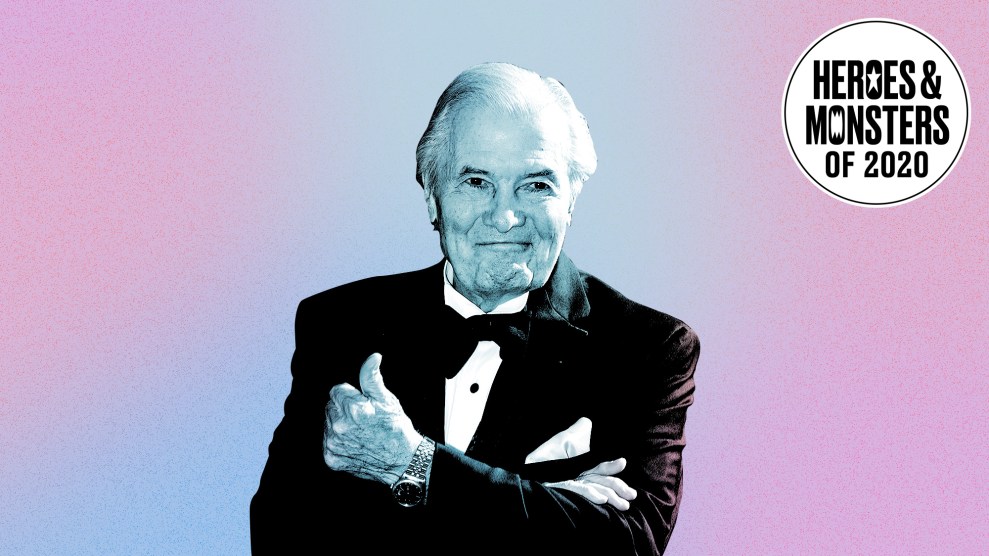

Mother Jones illustration; Prensa Internacional/ZUMA

One morning when the pandemic was a few months old, a roommate walked past me as I was cooking breakfast. He then turned around, confused.

“Are you making fucking deviled eggs at 9 a.m.?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied, and we laughed. But to be clear, I was not merely making deviled eggs. I was making Jacques Pépin’s “Eggs Jeannette“—a dish his mother made him when he was a child. It’s just one example of how this 85-year-old master French chef guided me through 2020 with his calming videos explaining how to cook for myself in ways that felt personally affirming, tender, even loving.

Pépin explains the secrets of Eggs Jeannette in a video, one of many the longtime cooking show host has uploaded through PBS’s YouTube page this year. He boils some eggs, disyolks them, combines the disyolks yolks with a persillade (parsley and garlic chopped together) and adds a bit of milk. He then adds this combination to the whites—making deviled eggs. But here’s where it gets interesting. Pepin then fries the deviled eggs in olive oil (yolks side down), gracefully using a fork to flip them. He places the fried deviled eggs atop a mustard vinaigrette, created with egg yolk detritus. Following the master, that morning, I too sprinkled some parsley on top.

As with most of Pépin’s recipes, this one is both simple and elegant, tasty when eaten and appealing when served. Granted, it takes more time than scrambling, but far less than you’d expect. I’ve loved making Eggs Jeanette, even on a weekday morning, moments before a Zoom call, which, of course meant I was late and would need to turn off the video so I could eat. And yet, that day—and on many other mornings during this year—I felt as if this was exactly what I needed to do.

“My mother would be proud of me,” Pepin says at the end of the video, looking affectionately at the dish. “Happy cooking.”

For the past few months, I have been happily, maybe a bit compulsively, cooking eggs (or should we say oeuffs?) with Pépin. I have watched his new PBS videos, “American Masters at Home,” and his classic “Fast Food My Way.” I have made his soufflé, his country omelet, his French omelet. I have learned the correct techniques with which to scramble, fry, and poach an egg. I have heard him say, time and again, beat the eggs firmly by going side to side in a bowl with a fork. I sprinkle herbs on top. He picks his herbs his from his garden; I pick mine at Safeway.

Just for a bit of context: Almost every morning I eat from three to six eggs. This year, that routine sometimes felt like just one more empty, never-ending ritual. There must be a way to make the essential fun, exciting, and new, I thought. And yet adventurous recipes felt like a burden, too bold, loud, inventive, and lacking the intimacy of home cooking. Cooking a poached egg to place atop a “Shalom Japan Lox Bowl” felt like going to a concert at home over Zoom: Good in theory, but just a reminder this all sucks. I was desperate to find a piece of how life used to be, preferably guided by a trusted friend who would let me follow along.

With Pépin, this year, I found that friend. I knew he grew to fame alongside Julia Child and the Craig Claiborne. That his New York Times Food section columns in the eighties became a gastronomic point of reference for a whole generation. Even today, he remains a famous, respected chef, uncontaminated by any bad behavior that have brought down others. But it took watching these videos—often late at night, unable to sleep—to understand why everyone loves him and his food.

His recipes are intuitive. He seems to understand that viewers will watch him cook, learn a general idea, and go off to enjoy their time alone in the kitchen. Dwight Garner, a fellow Jacques obsessive over the pandemic, and book critic for the Times in his spare time, connects this to Pépin’s impoverished childhood in wartime France, where he saw his mother learning to cook on rations. Each video focuses more on technique than the procession of ingredients. This is how you cut an onion, this is how you smash garlic, this is how you cut herbs. Slowly, my knife skills improved; I now salt properly (at least I think I do); and, finally, I know when to add balsamic vinegar to a vinaigrette (and when not to).

After my exhaustive exploration of eggs, I turned to a recent video for a sandwich, named after his wife, Gloria. He wears an apron with her name on it. And he makes a simple meal involving English muffins.

I scrolled to the comments, always so wholesome and friendly. This time they were filled with condolences and expressions of grief, because Gloria had died on December 5th.

That Pepin, a man whose sheer decency should somehow exempt him from the real world, should also consider 2020 a catastrophically terrible year came as a shock. I read the obituary and realized how little I actually knew about my pandemic companion. He has a kitchen studio in a guest house, for example, where he shoots some of his videos when not cooking “at home.” My intimacy with him was a false one. My intimacy with him was obviously not reciprocal, but by sharing the food he inspired me to make, led to a different kind of closeness with my friends, and those with whom I shared his wonderful food.

I fried eggs the morning after I read about his loss. I felt something like love for my modest morning cooking routine, in the midst of my-sadder-than-usual life. I made a few extra, in case anyone else I live with was hungry too.

An earlier version of this article misidentified the site of Jacques Pepin’s at-home cooking videos. They are shot in Pepin’s home kitchen.