Is our current sky-high unemployment structural or cyclical? Roughly speaking, cyclical unemployment just means the economy sucks and everyone is doing badly. Structural unemployment means that certain industries are doing badly, and the economy needs time to adjust as people leave declining industries and get retrained to work in healthier ones. Policywise, the difference is simple: we think we know how to attack cyclical unemployment: looser monetary policy, more federal stimulus spending, and so forth. But structural unemployment is a tougher nut. There are  things you can do to address it, but not much. Mostly, you just have to gut it out.

things you can do to address it, but not much. Mostly, you just have to gut it out.

So which do we have now? I think Annie Lowrey has the right take:

The problem seems to me to be both: The unemployment is cyclical and structural. Most sectors have suffered from the turndown, but job losses are concentrated in some industries: In residential construction, they are down 38 percent since 2006. (Between Aug. 2007 and Dec. 2009, unemployment in construction quintupled from about 5 percent to about 25 percent.) In health care and education, however, jobs are up.

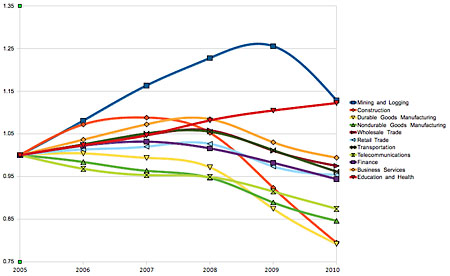

Here is a chart I made from Bureau of Labor Statistics data that shows the phenomenon. (The chart shows total jobs in major sectors since 2005.) Most sectors — retail trade, business services, wholesale trade, finance — have had moderate job losses one could reasonably chalk up to an economy-wide lack of demand. Let’s think of those as sectors characterized mostly by cyclical job loss. Then, there is manufacturing and construction. Jobs there have taken a nose dive, and the problem seems to be structural. Moreover, the job gains in education and health might thought to be structural as well.

The “normal” unemployment level is about five points less than it is today. I wouldn’t be surprised if perhaps three of those points are cyclical and two are structural. Unfortunately, too many people look at the structural component and throw up their hands. There’s nothing we can do about that! But we can do something about the part that’s cyclical. And even if we can’t get back to normal immediately, isn’t it worth it to get from 9.5% unemployment to 7% unemployment while we wait for the construction industry to rebound — or for all its excess workers to eventually find new lines of work? Of course it is. So what are we waiting for?