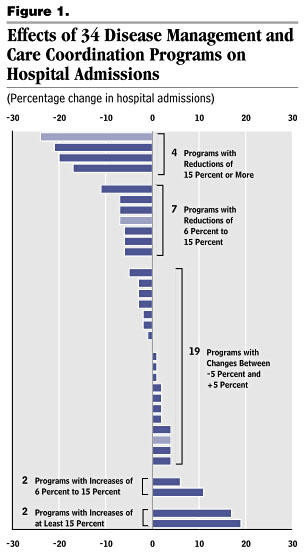

Today the CBO released a study of various demonstration programs designed to improve care and reduce costs for Medicare patients. One category of program, disease management and care coordination, attempts to get patients with chronic illnesses to understand their treatment better and take better care of themselves. The goal is to reduce hospital admissions. So how did that work out?

On average, the 34 care coordination and disease management programs had little or no effect on hospital admissions or regular Medicare spending…

Bad news! But maybe not. As the chart on the right shows, there was a very wide variance in the effectiveness of the programs. So while the average may have been zero, having lots of different programs  allows us some insight into which ones worked and which ones didn’t. For example:

allows us some insight into which ones worked and which ones didn’t. For example:

The programs used nurses as care managers to educate patients about their chronic illnesses, encourage them to follow self-care regimens, monitor their health, and track whether they received recommended tests and treatments. In most programs, the care managers were not integrated into physicians’ practices, and their contact with patients was primarily by telephone. In some programs, however, the care managers either were employed in physicians’ offices…Hospital admissions fell by an average of 7 percent and regular Medicare spending declined by an average of 6 percent for programs in which care managers had substantial direct interactions with physicians. In contrast, there was no effect, on average, on hospital admissions or spending resulting from programs in which care managers had little or no direct interaction with physicians.

So perhaps we’ve learned something. These kinds of program can reduce costs, but it turns out that financial incentives didn’t make much difference. What did make a difference was allowing the nurses doing the care coordination to spend a lot of time with the primary physicians.

Unfortunately, there’s some additional bad news. First, even the programs that worked didn’t reduce overall costs because their savings were less than the fees they were paid to implement the program in the first place. Second, it’s not clear that outcomes improved much: “Although the programs increased the percentage of beneficiaries who reported being taught self-management skills, they had little or no effect on the percentage who reported that they were adhering to prescribed self-care regimens.” Back to the drawing board.