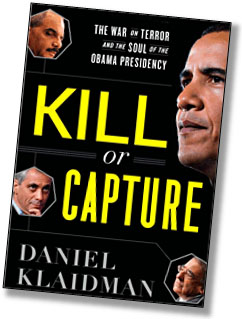

I just finished reading Daniel Klaidman’s Kill or Capture, a book about the evolution of Barack Obama’s national security policy during the first three years of his administration. It’s a good book to read if you want an answer to the question, “What happened?” That is, what happened to the idealistic Obama of the 2008 campaign who was going to shut down Guantanamo, end indefinite detention, try terrorist suspects in civilian courts, take civil liberties more seriously, and end the rabid secrecy of the Bush era? How did he turn into the guy  who not only didn’t do any of that stuff, but became a drone-obsessed killing machine in the process?

who not only didn’t do any of that stuff, but became a drone-obsessed killing machine in the process?

According to Klaidman, part of the answer is that Obama changed as he learned more about the reality of the fight against Al Qaeda. Another part of the answer is that, like all presidents, he succumbed to institutional and bureaucratic pressure. But for my money, the most telling passage of the book suggests that an equal part of the answer is that he simply never received any serious support from his own party.

Here’s the passage. To set the scene, it’s 2009 and Rahm Emanuel has just negotiated a deal with Senate Democrats to lift the congressional ban on the transfer of prisoners from Guantanamo in return for providing Congress with 45 days notice before any prisoner could be moved. This was, practically speaking, a distinction without a difference: 45 days was plenty of time to stir up a shitstorm of opposition that would prevent any prisoner from ever being transferred, and everyone knew it. But when White House aides held a meeting with the Democratic caucus, they found out it still wasn’t enough:

The administration officials nearly got their heads taken off, as anxious senators demanded to know how the White House planned to manage the exploding politics of terrorism. “Where’s your plan?” they shouted over and over again. Among the most agitated were liberals like Barbara Boxer and Barbara Mikulski, who were up for reelection. These were the same representatives who had pilloried the Bush administration for its fear-mongering tactics in the war on terror, but behind the grand doors of the LBJ Room, all politics were local. We’re going to get clobbered back home, the Democrats protested.

An adviser to [David] Ogden, watching the drubbing unfold in horror, handed a note to Ronald Weich, the Justice Department’s assistant attorney general in charge of congressional relations. It simply read, “I fear for our Democracy.” Weich, who knew the Hill as well as anybody in Washington, turned the piece of paper over and scrawled on the other side: “Welcome to my world.”

Obama knew all along that Republicans would pound him on national security issues, and as time went by it became increasingly obvious that this pounding would be extremely effective. But one of the things that made it almost inevitable that Obama would end up caving in on so many of his promises was the fact that Democrats wouldn’t help him fight back. In the end, maybe that didn’t matter. Maybe public opinion was simply too hardened on these issues. But the plain fact is that if the entire national security apparatus and the opposition party and public opinion and your own party are pretty much all lining up on the same side, there’s not much a president can do. This doesn’t get Obama off the hook, but it does go a long way toward explaining why he seemed to concede ground so quickly. If Klaidman is right, Obama struggled with this stuff persistently, but in the end no one was ever able to come up with alternatives that were both effective and politically feasible. Welcome to Washington.