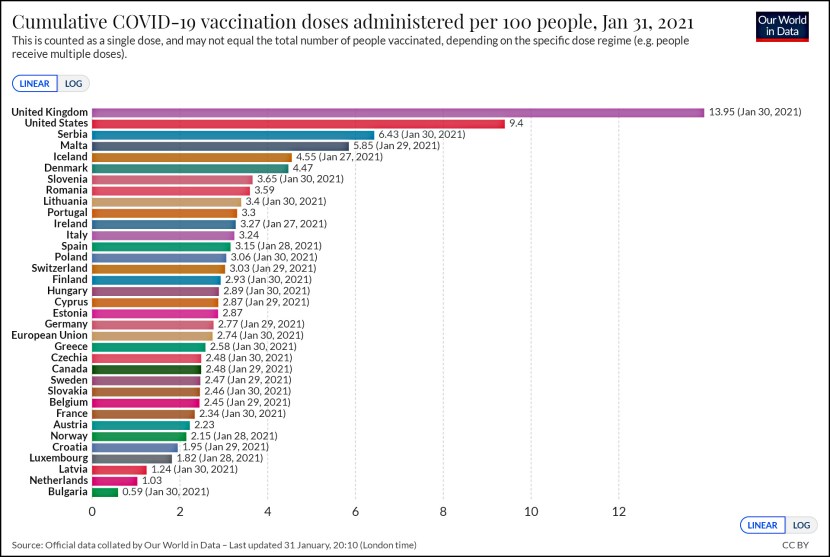

Keith Humphreys has a nomination for the most underreported public policy story of the past year: The continuing decline in the number of Americans who are behind bars or on probation/parole. Alex Tabarrok illustrates the trend with the chart on the right.

Keith Humphreys has a nomination for the most underreported public policy story of the past year: The continuing decline in the number of Americans who are behind bars or on probation/parole. Alex Tabarrok illustrates the trend with the chart on the right.

What’s going on? At the risk of sounding like a broken record today, part of the answer is probably lead. Lead emissions rose throughout the 50s and 60s, leading to a rise in crime through the 70s and 80s. Incarceration rates went up dramatically during the high-crime years, and many of the people put behind bars served long sentences. So even though crime rates started to fall in the early 90s, incarceration rates kept going up for a while as new criminals were added to a system that already had a lot of long-term residents.

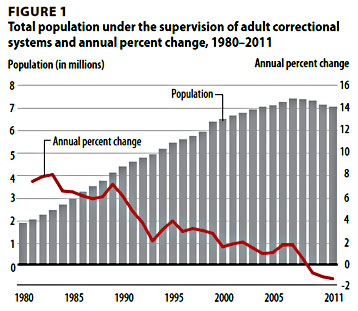

Eventually that turned around, and the incarceration rate turned around too. But it turns out there’s actually something even more interesting going on if you dig into the data. Rick Nevin, one of the lead researchers who played a key role in figuring out the lead-crime connection, has a short paper about incarceration rates at his website, and his key point is this: over the past decade, incarceration rates for young offenders have gone down, while incarceration rates for older offenders have remained high. (In fact, they’re actually up a bit, probably the result of recidivism.) The chart below shows the raw data:

Note how this fits the lead hypothesis. Young people, who were raised in the post-lead era, have sharply lower arrest rates than in the past and sharply lower prison rates. At the same time, older people, who were raised during the era when lead emissions were high, still have high arrest rates and therefore high incarceration rates. However, as the oldsters serve out their sentences and finally get too old for criminal activity, the lower arrest rates of young people are finally lowering overall incarceration rates. Nevin explains more in his paper, and also added a comment to my article with some additional details about black-white incarceration trends between 2001-11:

Over the same 10 years , the incarceration rate for black men ages 18 and 19 fell by 46%, and fell 40% for black men ages 20-24, and 31% for black ages 25-29. Over that same 10 years, the incarceration rate for black men ages 35-39 fell 12% and the rate for black men age 40-44 increased 11%.

….The incarceration rate is now declining for black males ages 35-39, but rising for white males in that age bracket, because that age group today reflects years when slum demolition in black neighborhoods reduced severe lead paint hazards over the 1960s, as urban sprawl caused more gasoline lead fallout in predominantly white suburbs.

You will often hear inaccurate and misleading statistics about the lifetime risk of incarceration for black males. That data reflects what the risk of incarceration was for black males born across years of pandemic lead poisoning, in urban slums with severe lead paint hazards and additive exposure to urban gasoline lead fallout. That “lifetime risk” does not apply to young black males today.

I’m going to caution everyone again that no one is suggesting that lead is solely responsible for the rise and fall of either crime rates or incarceration rates. There are plenty of other factors. But the evidence is very strong that lead plays a key role. And the good news is that since the drop in lead emissions is permanent, crime rates are likely to stay fairly low and incarceration rates are likely to continue to fall. Someday, instead of hearing about overcrowded prisons, we’ll be tearing down old prisons because there aren’t enough inmates left to keep them in business.