Over at National Review, Michael Strain chides Democrats for continuing to be obsessed with growing income inequality:

Income inequality has been growing at a much slower pace over the past ten years. Has anyone noticed? Beyond stabilizing, according to some measures, inequality has actually fallen since the beginning of the Great Recession.

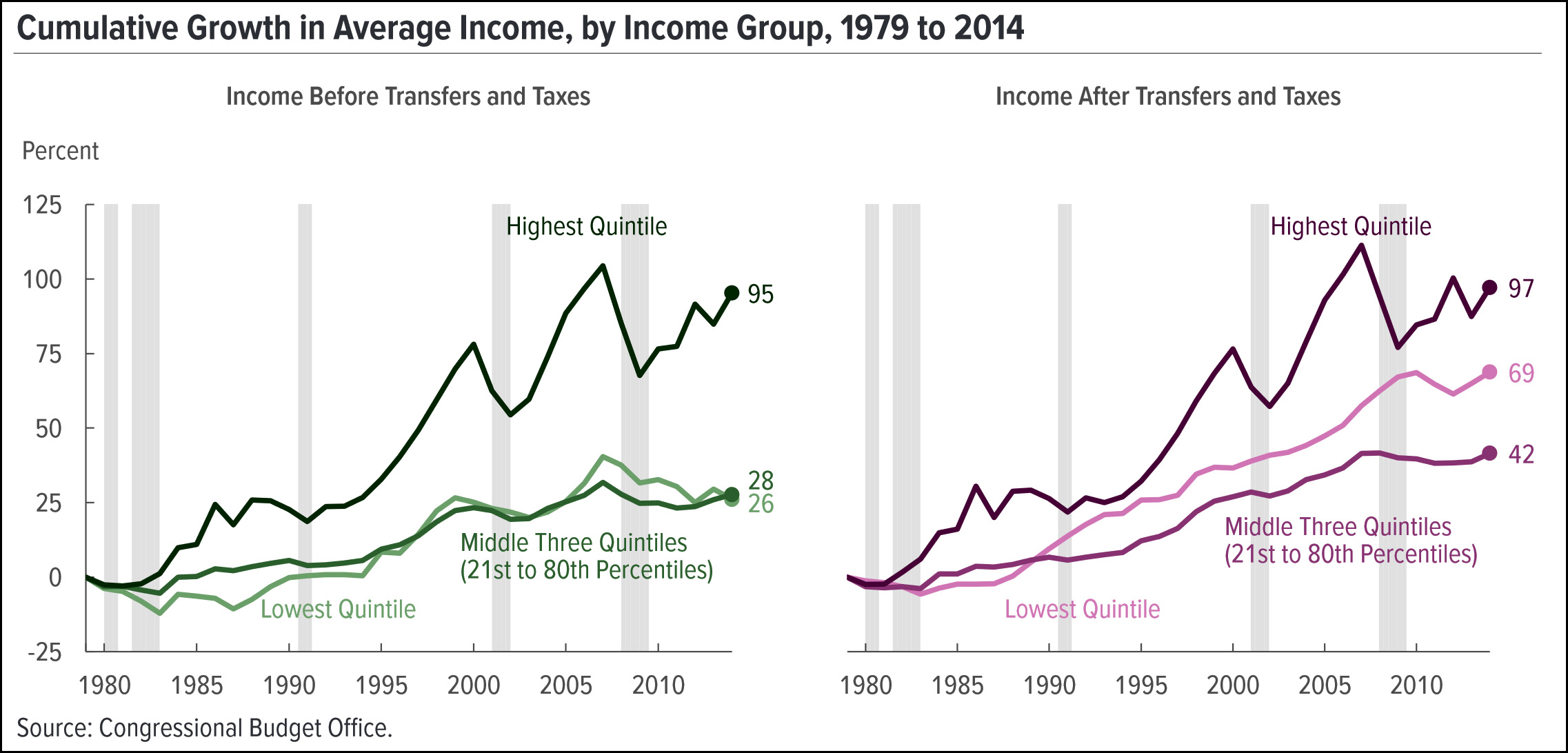

Hmmm. The single best source for a quick but rigorous look at income inequality is the Congressional Budget Office. Their latest report on income distribution goes through 2014 and it looks like this:

Technically, Strain is right. Compared to the beginning of the Great Recession, income inequality is down. But come on. It’s true that rich people took a big hit in capital gains income when the housing bubble imploded, but they’ve taken hits like that before and they’ve always bounced back. The same thing has happened this time. After a big loss, the rich began bouncing back almost immediately. Since 2010, their incomes have gone up by nearly half while the incomes of everyone else have declined. There’s no special reason to think this hasn’t continued since then. Most likely, income inequality in 2018 is higher than it was even at the height of the housing bubble.

There are ways to make this picture look better. If you include income from social welfare programs, incomes of the non-rich have been flat since the Great Recession, not down. Is that solace? Maybe a little, but not much.

Basically, the trendline showing the incomes of the affluent is an inexorable upward line since 1980 with a couple of spikes during the dotcom and housing bubbles. It just keeps rising and rising, and it’s still rising today. That said, I partly agree with Strain’s conclusion:

Part of the reason inequality features so prominently in the national conversation may have less to do with the rich and more to do with the lack of employment opportunities (until very recently, at least) and income growth experienced by many Americans….[Since 2007] median income grew by just 0.2 percent per year. It’s understandable to conclude, correctly or not, that others are doing better than you if your income is growing that slowly.

Whether the size of the gap matters more than the absolute economic condition of non-rich Americans is critical. Each implies different policy responses that are often in conflict.

If the gap matters, then policies that shrink it are good. For example, raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour and significantly strengthening labor unions may be good, because they will raise the earnings of many incumbent workers. But if we care about the economic condition of lower-income Americans, then these policies are counterproductive because they will reduce their employment opportunities. In the conflict between promoting income equality and increasing employment opportunities for lower-income Americans, I side with employment.

I agree that income growth for middle-class workers is ultimately more important than than raw income inequality. However, I very much doubt that labor unions and higher minimum wages are, on net, bad for the middle class. The disemployment effects of these policies appear to be pretty low, which the income-enhancing effects appear to be pretty large. I’m happy to consider other policies too, such as job subsidies, but the perfect should never be the enemy of the good. Nearly every policy worth its weight in white papers has some drawbacks. In the end I vote for all of the above: higher top marginal taxes, increases in the minimum wage, more union power, job subsidies, and anything else we can think of.